–

Denver’s vibrant and colorful mural scene can trace many of its roots back to the charged Chicano/a rights movements in the 1960s and ’70s. The Chicano movement stretched across the country, but the epicenter was the Southwest. Many of the issues that those activists were concerned about still exist today and Denver plays an essential role in the chronicling of those struggles — mostly through artistic means.

This is the stage that is set for the newest exhibition at the McNichols Building, curated by the Chicano/a Murals of Colorado Project, Para mi Pueblo. In it, nearly 30 artists display paintings that depict a variety of influences and topics related to the Chicano/a movement and to identifying as Chicano/a. Through this expansive display, viewers are not only given a visual history lesson, but they are also reminded that much of the current public art in the city is inspired by and because of Chicano/a leaders in Denver five decades ago.

In order to understand the significance Denver (and Colorado) had on the Chicano Movement, it’s important to acknowledge the work of Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales. Gonzales was born in Denver in 1928 and grew into a fiery activist, and boxer, who wrote the poem Yo soy Joaquín (I am Joaquin) in 1967. In this epic poem, he explained the identity of the Chicano as not European or American but also not Mexican, a new identity. This came from the idea that the Treaty of Hidalgo (a negotiation that ended the Mexican-American War in 1848) unjustly annexed the ancestral homeland of Chicanos called Aztlán — or the current US states of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Texas, Nevada and southern California. Yo soy Joaquín became an anthem for the movement. And Colorado, as the home of Gonzales and other well-known activists, became the epicenter of the Chicano cultural revolution.

A few artists, some of whom have work displayed in Para mi Pueblo, started the mural scene as a way to create for the Chicano cause. By the late ’70s and early ’80s, the predominantly Hispanic neighborhoods in Denver were exploding with proof of this new cultural revolution in the form of public murals. Some of those originals still exist — although others have been lost to time, weather and (more increasingly) gentrification.

The Chicano/a Murals of Colorado Project, which started just last year, organized the exhibition at the McNichols Building because of its mission to protect, promote and preserve these iconic pieces of Colorado’s cultural heritage. When everyone sees the booming street art scene we have in the city today, it’s mostly without the understanding that the way was paved by generations of Chicano/a artists.

Para mi Pueblo is more than an art exhibit because of this mission. Although there are not many informational texts to guide you through the expansive collection, it encompasses the Chicano movement and collectively narrates a cohesive story.

Stretching back to the beginning of the movement, the exhibit features the work of artists who painted murals in Denver starting in the ’60s — like Emanuel Martinez and Carlota Espinoza — as well as reproductions of murals painted in the ’70s and ’80s. These veterans to the Denver mural scene are displayed alongside contemporary muralists that currently paint in the streets, making Para mi Pueblo a diverse but united showcase. Not only is the message unified, but the aesthetics are strikingly complementary, so much so that the Chicano/a identity is understood with a resounding definition.

A complaint could be made that the exhibit does not rightly honor the importance of Espinoza, who is considered in some circles as the founding mother of murals in Denver. In 1966, she painted a set of two murals on Corky Gonzales’ Crusade for Justice Center. The building was bombed in 1973 and only one of the murals survived, A Tribute to Three Mexican Heroes. In many ways, that mural became the beacon of hope for Chicano/a artists in Denver and still to this day exacts a lasting impact. With only three small paintings displayed in Para mi Pueblo, her significance is washed out — to the unknowing visitor — by the bigger pieces in the room.

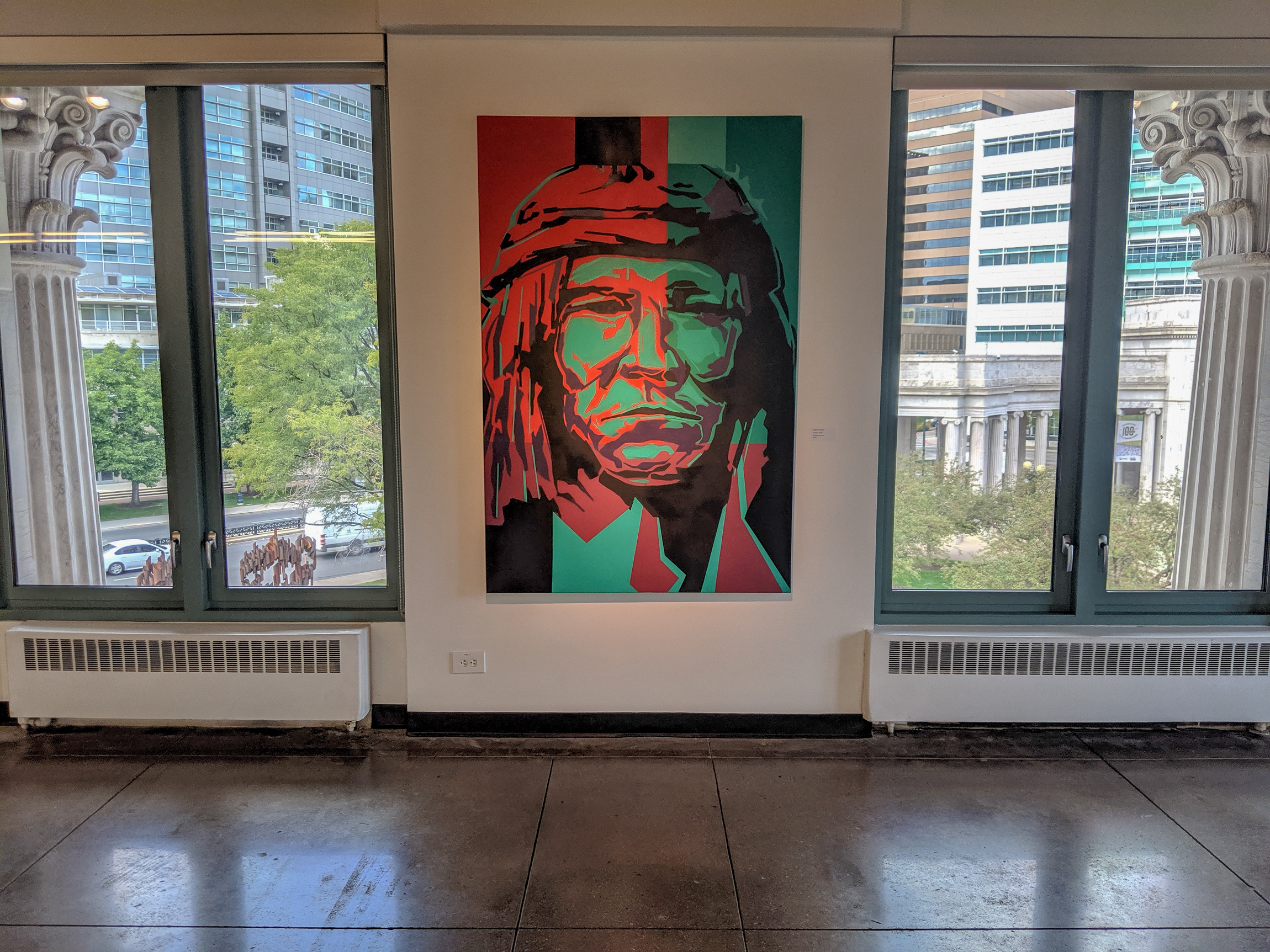

Although a large portion of the work displayed was painted within the last decade, the influence of those first pioneering muralists half a century ago is reflected especially with artists who have lived in Colorado most or all of their lives. The powerful colors and composition of Josiah Lee Lopez’s piece Cochise (2018), for instance, speaks volumes about strength, cultural identity and an urgent denial of the white-American identity. Lopez has attributed some of his success as an artist to his mentor and veteran of the Denver mural scene, Stevon Lucero.

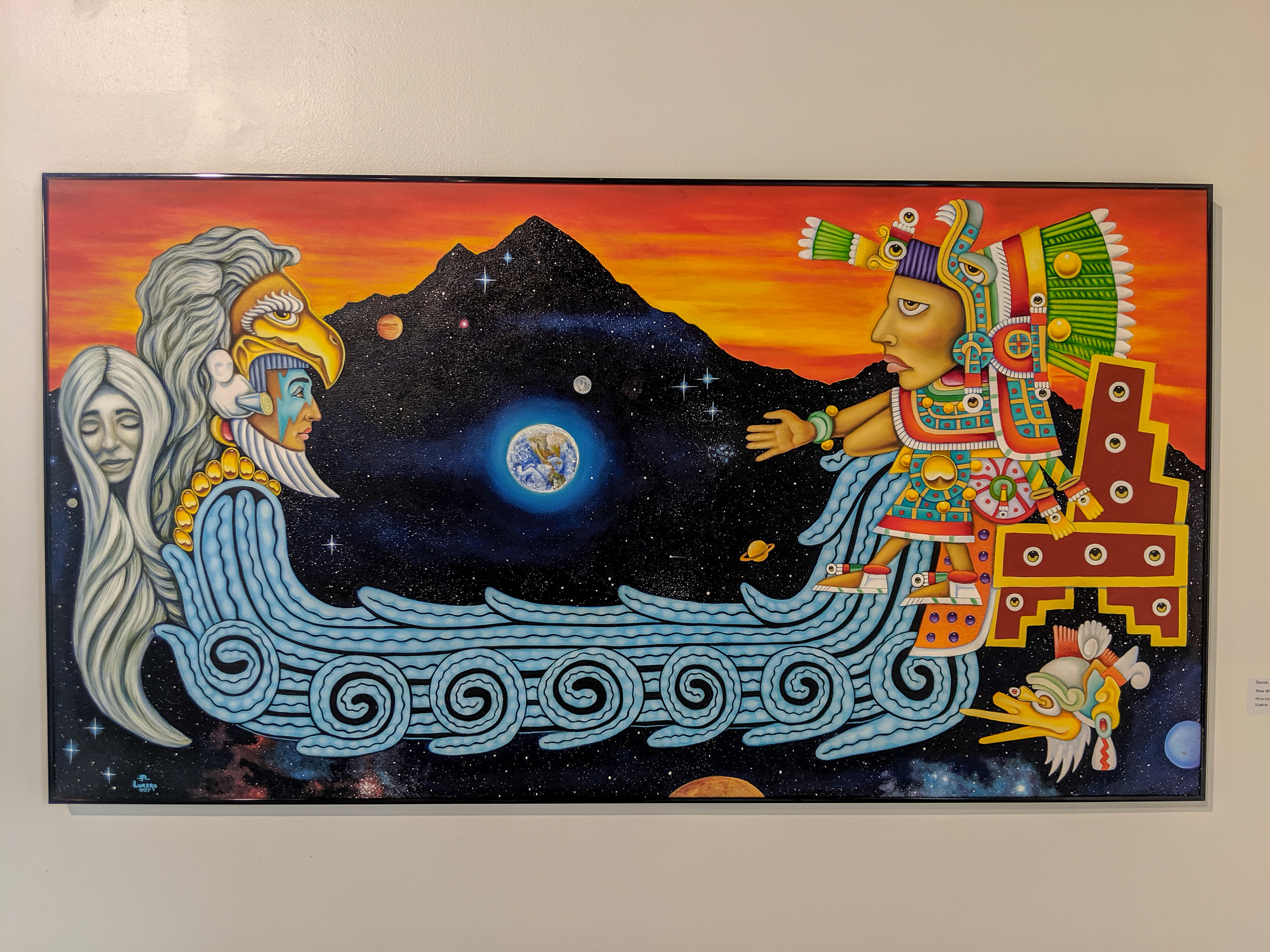

Lucero is a co-founder of the Chicano Humanities and Arts Council (CHAC) who moved to Denver from Wyoming in 1976 and began painting murals two years later. Throughout the years, he not only distinguished himself as a brilliant artist — even developing a term for his style of art, “Neo-Precolumbian” — but he has also lent his expertise, spirituality and intellect to aspiring artists through mentorship. Lucero has produced over 1,800 paintings in his career and two of his paintings are on display at Para mi Pueblo, one from 2003 and another from 2007 that perfectly embody that “Neo-Precolumbian” style.

At various vantage points in the exhibition space, smaller canvases are interrupted by full-size murals. At the west end of the building, four murals were painted specifically for the exhibit on moveable walls by Bobby MaGee Lopez and Karma Leigh, UC Sepia, Victor Escobedo, and Jerry and Jay Jaramillo. In the middle of the exhibit, however, one full-sized mural encapsulates the mission of Chicano/a Murals of Colorado Project. Originally painted in the ’80s by Jerry Jaramillo in the Sunnyside neighborhood in North Denver, Primavera was “sandblasted in 2014 after 30 years in a predominantly Chicano/a community, with complete disregard for the importance of the image,” as the description states. In 2016, Jerry worked with his son Jay to reproduce the mural on wood panels — and those same wood panels are what is on display at the McNichols Building.

READ: How Colorado’s New Poet Laureate Breaks the Mold and Will Change the Post Forever

Other artists showcased in Para mi Pueblo deviate from any historic vocabulary specific to Colorado but emulate the rippling effects of the Chicano movement through time and geography. The geometric work by Jason Garcia is inspired by the patterns found in Ojo de Dios or “God’s eye” — spiritual votives commonly found in Mexico.

The arresting portrait of a woman with barbed wire around her head, En Nuestros Manos (In Our Hands) by Leticia Tanguma gives a voice to a “Daughter of Aztlán” who portrays the current crises around Latino/a identity in the framework of the Chicano movement. Her father, Leo Tanguma, is a celebrated muralist from Texas who is best known in Colorado for his conspiracy-theory-arousing murals at Denver International Airport. Some of his work is displayed in this showcase as well.

Once every painting in the exhibit is seen, the special identity that activists like Gonzales strove to define is fully realized. For more than 50 years, these artists have actively shaped the art and culture scene, and perhaps nowhere more so than in Denver, where street art is attracting hundreds of thousands of “cultural tourists.” Not only does Denver owe a debt of gratitude to the early Chicano/a revolutionaries, but it also needs to stand up and acknowledge the continued influence of that movement in our vibrant and colorful city today.

—

Para mi Pueblo is on view at the McNichols Civic Center Building at 144 W. Colfax Ave., on the third floor until December 22, 2019. It is free and open to the public, Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

A full list of the artists displayed: Gregg Deal, DINKC, Victor Escobedo, Carlota Espinoza, Javier Flores, Carlos Frésquez, Ernie Gallegos, Anthony Garcia, David Garcia, Jason Garcia, Frank Garza, UC Sepia, Jay Jaramillo, Jerry Jaramillo, JOLT, Karma Leigh, Bobby Lopez, Josiah Lopez, Daniel Lowenstein, Arlette Lucero, Stevon Lucero, Onver Macias, Emanuel Martínez, Andy Mendoza, Tony Ortega, Rebecca Rozales, Carlos Sandoval, Leo Tanguma, Leticia Tanguma.

Rodolfo Corky Gonzales has a grandson who is a very talented Artist name Joaquin Gonzales

Joaquin _gonzales_art on Instagram.

Check him out