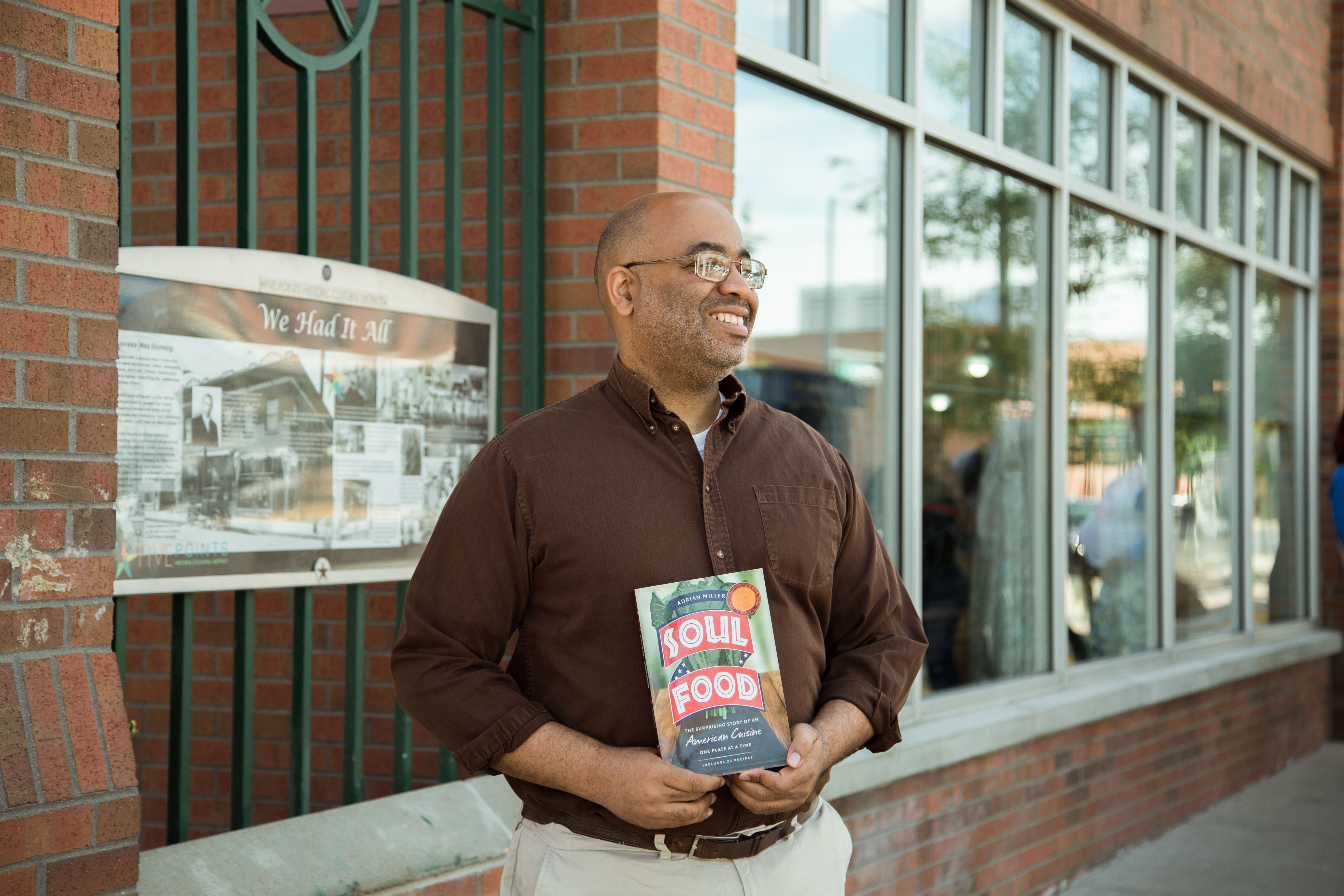

For those unaware, Denver is home to a James Beard Award-winning food historian. Adrian Miller — a Denver native, community fixture and former employee of the Clinton White House — has chronicled some of the most well-informed, exhaustive histories of this country’s black food traditions and stories. In his two books Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time and The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families Miller spins comprehensive and sometimes controversial narratives concerning just how important black people have been to American cuisine at large. Food history can be contentious, especially when multiple groups all have a claim to prized dishes. Miller does a good job of illustrating the complicated evolution many of these plates had to go through to reach their current position in the public imagination.

Miller’s erudite and stylish prose is peppered with food puns, personal anecdotes and recipes. Soul Food‘s tone is unusually conversational for a history book, which makes it a fun study for casual readers, historically-curious chefs and sociopolitically-minded food lovers. His next book Black Smoke will examine black influence on American barbecue with a planned release in spring 2021.

Miller was born in Denver. He spent some of his youth in Park Hill before moving to Aurora where he attended Smoky Hill High School. He went on to do undergraduate at Stanford where he walked with a degree in international relations, after which he attended law school at Georgetown. For some time he had ambitions to be a senator from Colorado but found his way to Washington under different auspices.

While in D.C. Miller served as the Deputy Director for the Initiative for One America — a brilliant and underfunded organization that worked to reach out to different sectors to talk about diversity, with racial, religious and ethnic reconciliation as the goal. “The idea was that if we talked and listened to one another we would realize we have a lot more in common than what divides us,” said Miller. Beginning in October 1999 and ending at the start of the Bush administration, Miller’s time in Washington provided valuable inspiration for his coming authorship. His work tells the real story but does so in a way that invites conversation rather than proselytizing. It was during this time he began to approach history as a “side hustle.”

Researching Soul Food required extraordinary scholarship. In 2011, Miller cashed in his retirement to work on the book — moving his research from side hustle to centerstage. He read through 3,000 oral histories from formerly enslaved peoples compiled by George Rawick in The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography — creating an index that collected any mention of food or cooking. From there an additional 500 cookbooks, thousands of newspapers and hundreds of interviews all had to be digested, and this was before the food tour. Miller embarked on a journey that covered 150 soul food restaurants in 35 cities across 18 states — Washington, Oregon, California, Colorado, Texas, Illinois, Mississippi, Tennessee, Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, the Carolinas, Virginia, New York, D.C. and Massachusetts all received a visit. The book reflects a sincere commitment to both library and table. Soul Food came out on August 15, 2013, and went on to win the 2014 James Beard Award for Reference and Scholarship.

“Want to know something crazy? Only three out of the 33 inductees of the Barbecue Hall of Fame are black,” said Miller. This astounding statistic is part of a cultural problem that the author hopes to address in Black Smoke. Miller intends to redirect the current barbecue narrative — one he feels has been unfairly shifted to favor white chefs. “Before the 1940s it was wonderfully diverse,” he continued. The historian cites the advent of food television, the rise of foodies, the resulting need for content and the explosion of barbecue onto the national food scene for helping to reshape barbecue as “craft culture” in the public imagination. While this has certainly produced some great food and world-class chefs, it has left plenty of deserving, mostly black, chefs without due recognition. With Black Smoke, Miller hopes to provide the antidote.

Miller currently works his day job at the Colorado Council of Churches — a state-wide ecumenical social justice organization — while continuing to write and research Black Smoke. He also gives informative and entertaining presentations to campuses, corporate retreats and bookstores. He’s become a national authority on his subject — the Washington Post recently called him requesting historical context for KFC’s new chicken and doughnut sandwich. Rather than playing into the chicken and waffle narrative, most outlets have been using, Miller dropped more formidable knowledge. “It’s more like The Luther,” he said, not missing a beat.

Adrian Miller’s books are all available directly from his website.

All the food was shot at Welton Street Cafe at 2736 Welton St., Denver. It is open Tuesday and Wednesday 11 a.m. – 8 p.m., Thursday and Friday 11 a.m. – 10 p.m., Saturday 12 p.m. – 10 p.m. and Sunday 12 p.m. – 5 p.m.

All photography by Adrienne Thomas.