Graffiti was born out of the postmodern movement in the 1960s, early 1970s, where creatives were looking for ways to express themselves beyond a gallery or museum, resulting in an underground subculture that figuratively flipped the bird to the established art world. Street art is typically associated with softer origins — instead of the rebellion inherent in graffiti, it is motivated by beautification, in an innocent sense of the term. Especially in Denver, the rise of street art as a popular and accepted art form bloomed much later than graffiti — in the mid-2000s.

It’s easy to focus on the newer, enterprising street artists with dozens of murals popping up every month. But the history of graffiti is thick with information about society on a grander scale. Much like punk, hip hop and skateboard cultures, graffiti artists have represented an aesthetic and lifestyle that keeps attracting an ever-growing network of like-minded individuals. It started as a grassroots movement and since has become a defining moment in art history where overlooked artists no longer asked for permission — or jumped through hoops, or went to school, or used fine art materials — to show the world their art. Naturally, not everyone understands or appreciates the rogue tactics and the mentality behind graffiti, which has always further marginalized it from established art norms.

With the recently burgeoning mural scene, old-school graffiti artists sometimes are faced with a dilemma — become a street artist or find another way to express yourself. In some ways, it feels like graffiti is on the endangered art list. But in other ways, like in the current show on display at Mirus Gallery L’Avenir: A Graffuturism Group Exhibition, graffiti as we’ve known it is only the beginning. On view from April 27 through May 25, 2019, this collection explores the influence of graffiti on current artistic practices, and more specifically, how graffiti artists are redefining contemporary art. “L’avenir” in French, translates literally to “the future” and in this case, it refers to the emerging movement of Graffuturism.

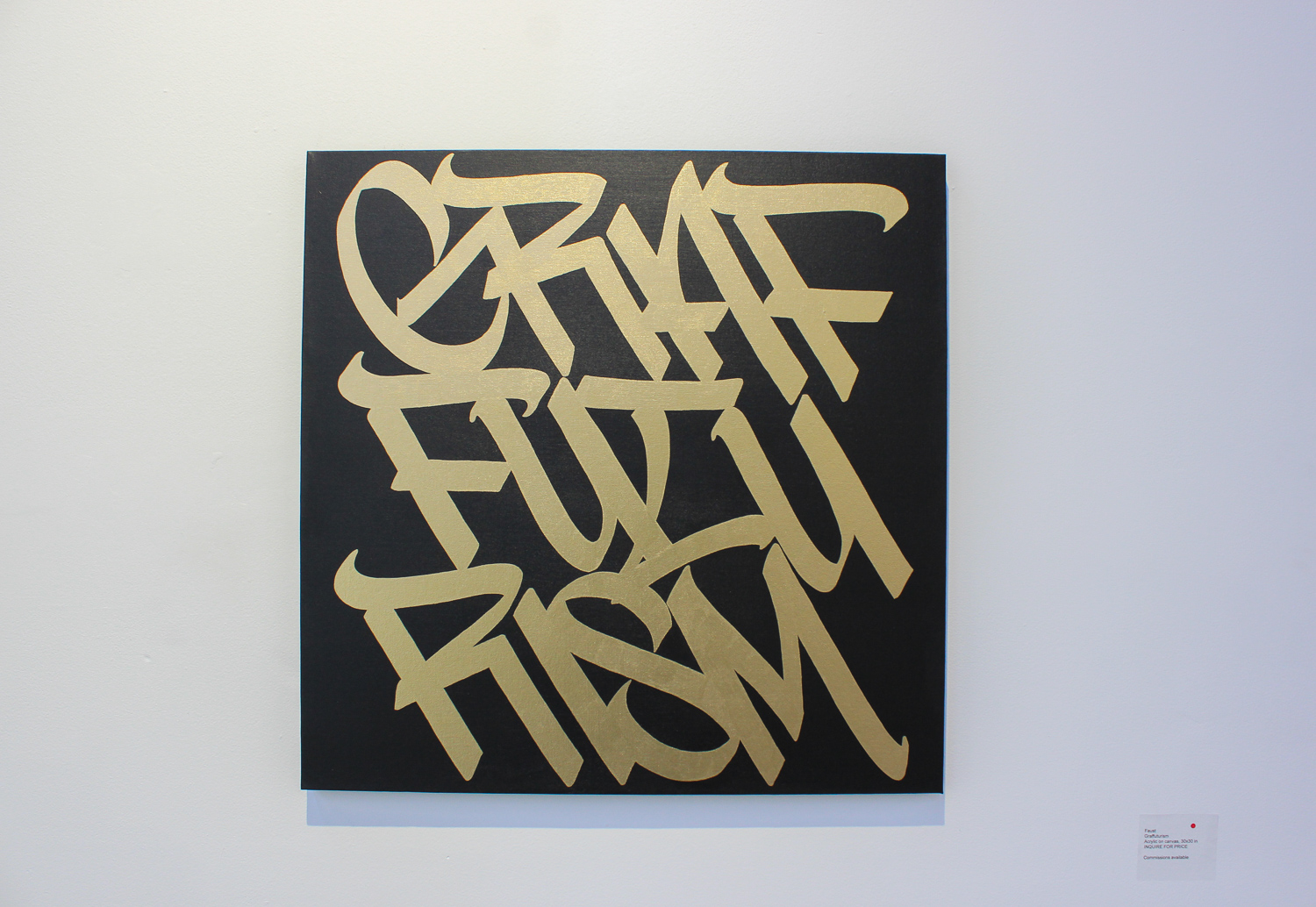

Curated by an artist known as Poesia, L’Avenir includes a large group of international artists who all share the common connection of past experience in graffiti and urban art. In 2010, Poesia started a blog called Graffuturism, where he sought to showcase the work of graffiti artists he felt were underrepresented. The term came organically, referencing other art movements with the inclusion of the “ism” at the end, but also shying away from the rigid structure of a movement by starting with “graff” — a harsh sounding phrase that embodies the attitude behind graffiti. Poesia stated, “Graffuturism is just another word. The real power of our art form is in our actions as artists collectively.”

L’Avenir certainly relies on the power of a collective, with over 35 artists on display. Some of the more recognizable names on the list include Okuda San Miguel (who displayed at Mirus last year with a solo show), Doze Green — an artist known for his live painting performances and mixture of graffiti calligraphy with Cubist flare — and well-known street artist from the 1980s in South London, Remi Rough.

With so many different styles, the impact of the show is rough around the edges. But the idea behind it is something worth biting into. The idea that graffiti deserves a place in the annals of art history, and not as a side note in city manuals about curbing vandalism. And the idea that graffiti is not a thing of the past, but rather the start to something brand new — a monumental task in the decorated and vast halls of canonized art. L’Avenir — and Graffuturism as a larger movement — spreads the notion that graffiti artists are not confined to the streets, and that there can be a space on the wall inside a gallery for them if they want to take that path.

Even if the show lacks a cohesive way to explore these concepts as a viewer, it provides many examples of the way graffiti has already influenced popular aesthetics and design. It offers a sweeping portrait of the emerging movement and sets the stage for further development. The array of aesthetics — from the color-blocked abstract pieces by Tobias Kroeger to the spray painted canvases by Kenor to the black marker sketches of David Mesguich — emphasizes the broad definition of Graffuturism and the inherently complex definition of graffiti.

—