Broadly speaking, contemporary art needs innovation in order to distinguish itself from the traditional canons of art. Without artists who take risks, or who are ahead of their time, art would stay stagnant and unrelatable. The three new exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver (MCA) offers viewers a look at artistic innovators who have already or will influence other contemporary artists with their pioneering styles. Although not directly related to each other, the three exhibitions present a somewhat hierarchical range of innovators — from the world famous Georgia O’Keeffe to the largely-well-known tattoo artist Amanda Wachob to the local artist Andrew Jensdotter.

Aftereffect: Georgia O’Keeffe and Contemporary Painting

O’Keeffe is already known as one of the most significant American artists of the 20th century, a woman who forged new paths in abstract painting, often highlighting floral shapes, vast landscapes of the Southwest and skulls. But in the exhibition curated by Elissa Auther (from the Museum of Arts and Design in New York) and consulted by artist Emily Joyce, the attention is turned from O’Keeffe’s more obvious influence to the nuanced approach of 12 different artists who emulate O’Keeffe for a variety of reasons.

Taking over the second floor of the MCA, Aftereffect guides viewers through the galleries and through O’Keeffe’s career but uses the work of artists inspired by O’Keeffe to tell the story in a new way. The exhibition entices those who came for O’Keeffe to complete the entire course, teasing with only one or two of her actual paintings per room. In total, there are eight O’Keeffe originals and several dozen other paintings from the 12 contemporary artists.

Beginning with Lesley Vance, the exhibition includes a quote from each inspired artist about their relationship to O’Keeffe’s work or to O’Keeffe’s life. Joyce and Auther conducted interviews will all of the artists involved in order to better understand the impact of O’Keeffe on their practice. Vance’s quote is “As a girl growing up in a Milwaukee suburb, the first artist I remember learning about was Georgia O’Keeffe, because she grew up in Wisconsin. I feel a personal connection that goes beyond the formal kinship I feel with her work.” This sets the stage for the rest of the exhibition because it illustrates so easily how O’Keeffe pioneered not only a creative style, but also a creative persona — regardless of O’Keeffe’s own interpretation of her reputation and art during her life. This idea of her creative persona is as important to her enduring legacy in this exhibition as the impact of her innovation in abstraction is.

To those unfamiliar with the vastness of O’Keeffe’s work, there will be parts to Aftereffect that seem wholly unrelatable to the style of the famous artist. But the beauty of the collection is in the nuances. Each room uses the few O’Keeffe originals as the foundation, and the rest of the artists’ work pivots around those pieces. In the second room after Vance, the impact of O’Keeffe can be experienced as ripples through time. Many of the artists featured in this room, like Carrie Moyer and Corey Drieth, speak to how they feel the emotional vitality of O’Keeffe when they look at one of her pieces. It seems as if, for these artists, O’Keeffe’s spirit lives on through her paintings and the appeal of emulating that should be obvious.

One of the highlights of Aftereffect is a site-specific piece by Melissa Thorne, which features a wall painted from floor to ceiling, overlapped with four pieces dedicated to four distinct seasons. At first glance, the entire scene is only geometric. But once you understand that it depicts the landscape of the Catskill Mountains in New York — a hyper-simplified version, much like the pixelation of early video games — the ingenuity of it is mesmerizing. Her quote explains, O’Keeffe’s landscapes are simplified and concise, and I try to apply that idea of brutal editing to my own work, constantly trimming down, seeing how much can be excised.” Through an artist residency in Santa Fe, Thorne discovered that O’Keeffe had a large collection of color chips to use for different subjects in her paintings, so she did something similar for herself. Thorne now creates a new palette of colors based on selected locations, like the Catskills.

Don’t leave the second floor without watching the short video in the corridor, Land of Enchantment: Southwest USA — a clip that trims down O’Keeffe’s legacy to a cliché, paired with some of the artists’ reactions to such a simplified version of the artist they emulate and admire. The other artists featured in this exhibition are Emily Joyce, Loie Hollowell, Matt Connors, Jeffrey Gibson, Gretchen Marie Schaefer, Mary Weatherford, Leslie Smith III and Mary Heilmann.

Amanda Wachob, Tattoo This

The MCA continually forges new paths in the contemporary art world, focusing on content that is prevalent in modern culture but usually missing from other museums. Amanda Wachob’s Tattoo This is another shining example of this progressive stance toward contemporary art.

In the exhibit, you’ll find Wachob’s previous tattoo designs, as well as art inspired by tattooing or made with tattooing tools. This week, there will even be live tattooing. Many of the previous offbeat exhibitions in the last decade at the MCA have been due to the exploratory curatorial efforts of Adam Lerner. Although he just announced his departure from the museum, Tattoo This is one of the last (or maybe the last) exhibition before he will not renew his contract in June. But it serves as a fitting finale for the curator, who also had the foresight to spotlight artists popular in other subcultures, like Mark Mothersbaugh and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

READ: Watch a Nationally-Acclaimed Artist Tattoo People at the MCA This Week

Beginning with Wachob’s earliest attempts at what is now considered her iconic style of watercolor tattoos, Tattoo This expresses to viewers the intimate relationship that is possible between gallery-quality fine art and tattoos on skin. This would not be quite as eloquent without the pioneering inventiveness of Wachob, who turned her ability to paint on paper with brushes into a technique executed with needles and ink on human subjects. Her journey toward exhibiting both photos of her tattoos and other art inspired by tattooing in museums started in earnest in 2008, when she experimented on some friends and posted pictures — which went viral. At first, the tattoos appeared closer to colorful bruises than watercolor, but with each new tattoo, Wachob mastered her own invention. The first room of her exhibition shows viewers how her style evolved — from the gestural bruises to calligraphic strokes to the marbling effect that she now mainly employs.

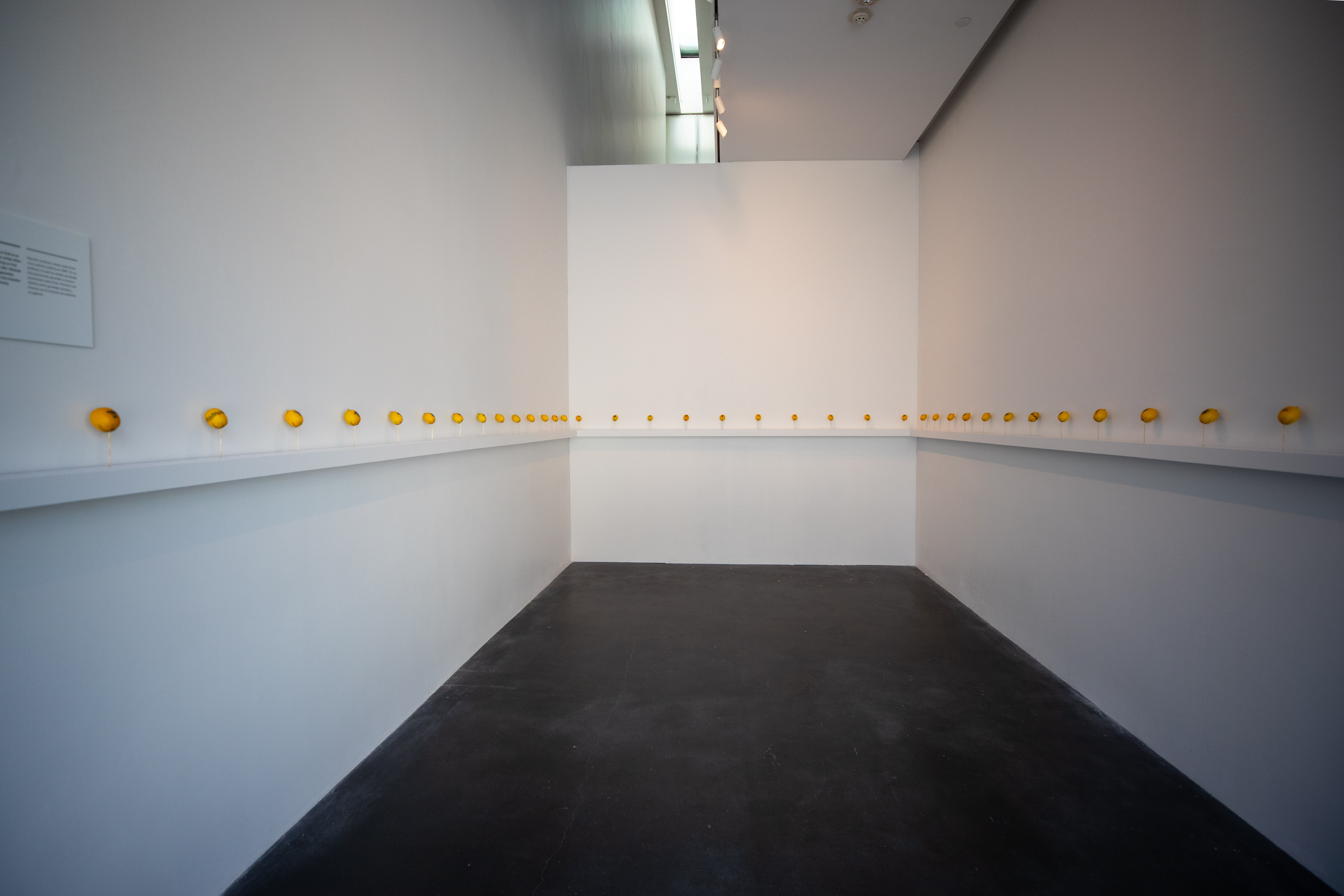

The next room features 40 lemons — all tattooed by Wachob using a tattoo gun and blue ink. In the early days of her learning curve with tattooing, Wachob practiced on citrus fruits like lemons because they replicated human skin well enough. Not only are the lemons visually pleasing in this showcase — all in a line around the room, resting perfectly atop identical custom-made mounts — they signify a certain temperament of Wachob. Without the willpower, determination and resolution it would take to tattoo countless lemons, she would not have the experience to experiment with the process itself. Although this room might feel cute and fun, it subtly speaks to the tireless work Wachob went through to be the maven of tattoo art she has become.

The final two rooms are dedicated to Wachob’s work that uses the tools of tattooing, which is an essential part of her innovative role in the worlds of contemporary art and tattoos, simultaneously. Instead of showcasing the proof of tattoos, (like photographs of people who have them on their body), the art on the walls in the second half of the exhibition is dedicated to things like tattoo ink, the way a tattoo gun interacts with different materials and sketches for “flash” tattoos. Wachob (until February 21) will be live tattooing 11 lucky people in the third room, surrounded by large-format works which begin with tattoo ink but end as lovely marbled abstractions. First, Wachob drops the ink between two pieces of paper and presses them together. She then photographs the mixtures and transfers the photographs to the canvas. The 11 people who will receive the tattoos in this gallery managed to secure their spots within six minutes of Wachob opening the application on her website. If that’s not a testament to the power, draw and popularity of artistic tattoos, then maybe nothing is.

Andrew Jensdotter, Flak

In the lower level gallery, a showcase of an incredible local artist has been curated by Zoe Larkins, titled Flak. It is Jensdotter’s first solo museum show, a milestone since the artist received his MFA from the University of Colorado, Boulder in 2014. His work feels right at home alongside the other innovators showcased in the museum because he continually experiments with his materials. Two paintings highlight a technique he has started to gain some recognition for, a process he calls “carved painting” where he layers hundreds of different colors of house paint and then carves out circular shapes to reveal the striations of color. He decided to include these two because they portray American icons.

The first portrait that greets viewers when they walk down the stairs into the gallery is the famous baseball player from the early 1900s, Honus Wagner. Modeling it after an equally famous baseball card, Jensdotter’s carved circles hint at the shape of a human without needing any facial expression or other specific details. Across the gallery, the second carved painting is a little harder to pick out as a person, but it depicts the unmatchable Judy Garland. Jensdotter intentionally creates these illusionary devices through which to see his subjects because he is relating to the “untruths” of modern society and political discourse. Do you ever know who a celebrity is? Does it matter?

The other five pieces in the show, although deviating from the carved painting path, show how Jensdotter’s approach to his materials and process may never be pigeonholed. With the three pictured above, Jensdotter began using spray paint and plastic sheets t0 imprint patterns onto the canvas. First, he spray paints designs onto the plastic sheet, then he carefully places the wet spray painted plastic onto the canvas, where the patterns remain. Jensdotter likens the fragility of working with spray paint in this capacity as working with “butterfly wings” — although that delicacy is hard to notice when you first see the complicated landscapes. Like the carved paintings, he uses many layers in order to infuse complexity, depth and the right amount of shading and highlights.

Even though it’s easy to get lost in the process and materials of this show, Flak is about the impact of current events on the artist. Because the works are emotive in this way, there’s an immediacy that is lacking in other abstract contemporary art of the same aesthetic. Jensdotter pulls from his own experiences and also eludes to larger motifs of American society — graffiti culture, the mushroom cloud of a nuclear bomb, famous celebrities and the dilemma of capitalism.

It is with that last motif that the artist created the breathtaking piece made of broom heads, called “The Spirits I have Called.” Conjuring the symbolism that many of us relate to our childhood memories of the movie Fantasia, the circles of brooms originating from a single point speak to the compounding separation between our work and how things are made. This is the best way to finish all three exhibitions because it reminds the viewer to consider the labor of an artist as much as the finished product. It reminds us that art is so fantastically varied because artists like the ones displayed at the MCA seek the new, the innovative and the path never traveled before.

—

All three exhibitions are on view until May 26, 2019. The MCA Denver is located at 1485 Delgany Street. Hours are Tuesday through Thursday, noon to 7 p.m., Friday from noon to 9 p.m. and Saturday and Sunday from 10 a.m to 5 p.m. More information is available here.

All photography by Heather Fairchild.