This year there are 13 statewide measures in Colorado that voters will decide on by November 6. Seven of them are citizen-initiated and six have been referred by state legislature. Among the measures, voters will have to decide between two different propositions about transportation projects, two amendments that deal with redistricting and two competing measures that largely deal with oil and gas development. Unfortunately, the wording in the ballot can be confusing and needlessly complex. Ballotpedia uses the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level and Flesch Reading Ease formulas to figure out just how complex the wording is, and the Colorado ballot can be as complex as “grade level 37” — which means you’d generally need at least a Ph.D. to understand it. Don’t worry though, we’ve broken down each measure to make it easier to figure out how you’ll want to vote. Study up and feel informed when you check the boxes this year.

The following text was adapted from the 2018 Colorado Blue Book. The full document can be read here. We also recommend that you refer to this site for judge recommendations, as that is not included in this guide.

Amendment V: Lower Age Requirement for State Legislators

What: Amendment V proposes lowering the minimum age requirement from 25 to 21 years old for people serving in the Colorado state legislature. Currently, 43 states have a minimum age requirement between 18 and 21 for state representatives, leaving Colorado as one of the minorities who require older than 21 years old. Half of the states require between 25 and 30 years old for senators, including Colorado. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, Colorado’s average age of legislator in 2015 was 55, a decade older than the average age of Colorado’s population. This amendment would lower the age to 21 for both prospective representatives and senators.

Pros: The most cut and dry argument for passing this amendment is that citizens of Colorado (and of the greater US) are considered adults at 21 years old. Once they are considered adults for every other purpose, it only makes sense that they can run for office. Voters can decide if they are “too young” or not, but limiting those who may be more mature than their peers is not a fair restriction.

Cons: Since the amendment proposes the change for both senators and representatives, the current restriction of 25 years old is not only “average” on the national level, it allows the legislators to have more life experience. Some people feel that at 21 years old, candidates would not have enough expertise to be effective in office.

Cost: There is no impact from the passing or blocking of this amendment.

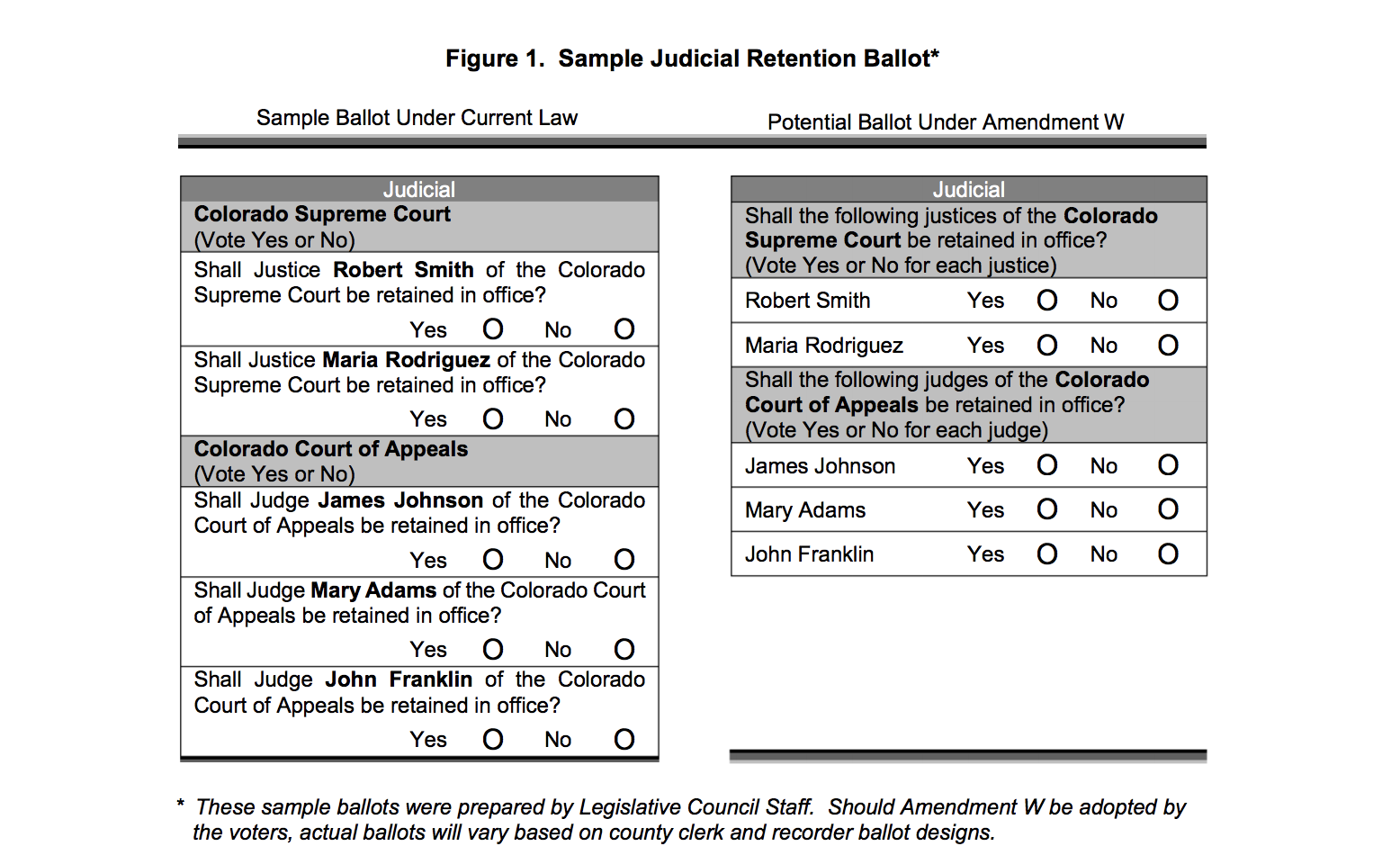

Amendment W: Election Ballot Format

What: Amendment W is about how justices and judges should be listed on your ballot. It’s a design question aimed at making your ballot more compact. Under this new system, when you are asked if judges and justices should be retained, they will be listed under a category based on what type of court they serve. Before, each time you voted for a judge it repeated this information for each individual. This new system removes that repeat information. It can be hard to understand unless you see it. See above for an example ballot, but keep in mind this might not be the exact design.

Pros: Proponents argue Amendment W will make voting more efficient and ballots shorter. In turn, it will turn increase voter participation. Also, shorter ballots can decreasing printing and mailing costs and therefore might save money.

Cons: Opponents of this measure believe that removing the additional information could cause confusion because it might lead voters to be unsure if they are voting for a group of judges or justices or for individuals. They believe this confusion could decrease voter participation.

Cost: It could save money by slightly lessening the workload of the county clerk and recorder and may reduce ballot printing and mailing costs.

Amendment X: Industrial Hemp Definition

What: Amendment X proposes removing the definition of “industrial hemp” from the Colorado Constitution and using the definition provided in federal law or state statute instead. Currently, “industrial hemp” is defined as a marijuana plant that contains less than 0.3 percent of THC, both in the Colorado Constitution and federally. If Amendment X passes, the definition will be removed from Amendment 64 and all matters relating to the cultivation of hemp will be left up to the federal government’s standards.

Pros: Some who are currently involved in the hemp industry feel that the current definition in the state constitution limits the future of hemp production, especially if the federal government decides to change their definition of hemp. For instance, if the 2018 Farm Bill passes allowing “industrial hemp” to have up to one percent THC, Colorado will fall behind in its production because it will be limited by the 0.3 percent definition.

Cons: Amendment 64 passed with a majority of the voters agreeing on the measures and definitions within. Overturning one part of that Amendment may go against what some of the voters originally wanted when voting to approve it. Also, allowing the federal government to dictate the definition of hemp may lead to regulations imposed on hemp farmers that do not align with Colorado’s opinion on the plant. Currently, all cannabis varieties including hemp are considered controlled substances and enforced by the Drug Enforcement Agency, proving that the federal government does not see hemp as an agricultural commodity.

Cost: This Amendment does not affect the revenue or expenditures of state or local government agencies

Additional information: This Westword article provides quotes from both sides of the argument from people currently involved in the Colorado hemp industry. Also check out this article from KUNC with a better description of the possible outcomes from passing the Amendment.

Amendment Y: Congressional Redistricting

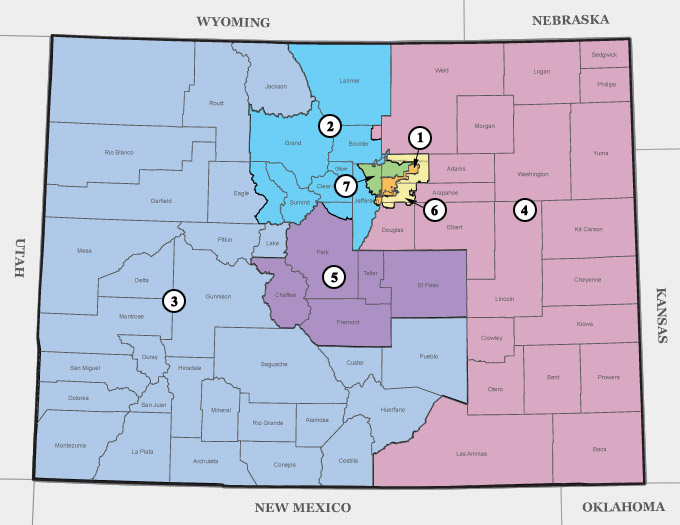

What: Amendment Y, much like Amendment Z, aims to combat gerrymandering— a process of “drawing the boundaries of electoral districts in a way that gives one party an unfair advantage over its rivals.” (If you need a more visual explanation of gerrymandering, you can find a really good one here). Amendment Y tackles the drawing of those electoral districts for congressional seats. Currently, the map is decided by the state legislature but Amendment Y proposes creating a new commission that will approve a map drawn by nonpartisan legislative staff. This new commission will consist of 12 members with an equal number of members from each of the state’s two largest political parties and unaffiliated voters. As it currently stands, this would mean four Democrats, four Republicans and four unaffiliated voters. Additionally, their approval of the map must be reached by a supermajority vote. The commission is chosen by a rather complex process that aims to prevent an unfair selection of commissioners. This includes strict rules of who can apply to be a commissioner (i.e. no one who has been a politician, lobbyist or paid political operative within the last three to five years), creating a panel of recently retired judges to help select commissioners and using random selection for six of the 12 commissioners (note: the six are pulled out of a pool of 150 applicants that meet the application standards). In addition, the commission must reflect “Colorado’s racial, ethnic, gender, and geographic diversity, and must include members from each congressional district, including at least one member from the Western Slope.” The development of the map will also be open to public meetings to allow feedback from voters and the map must adhere to the Voting Rights Act. Additionally, the commission is given criteria to keep communities of interest, cities and counties together while maximizing political competition and prohibiting maps that weaken the electoral influence of any racial or ethnic group or that protects incumbents, political candidates, or political parties. It’s an incredibly complex process, so for the full explanation of the process and application rules, refer to the Blue Book.

Pros: Proponents of the measure argue that Amendment Y will limit the role of partisan politics and create more compromise in congressional redistricting by creating checks and balances so not one political party controls the commission. Similarly, this new system allows for more transparency because the commission is subject to state open records and open meetings laws. Also, there is more opportunity for public participation across Colorado because the commission will host public meetings throughout the state. Lastly, those who agree with the amendment say that it creates more structure in the process of redistricting by providing clear criteria that prioritize communities of interest, city and county lines and political competitiveness.

Cons: Opponents of Amendment Y argue the new system removes accountability since most of the people involved in the process (from the commissioners to the judges) are not elected officials and therefore are not beholden to voters. Also, the process of choosing commissioners is complicated and at times decided by random selection and therefore might not pick the best individuals. Similarly, it may be difficult to understand the political leanings of the unaffiliated voters, who will often be the determining vote in the decision of the map. Lastly, the criteria for drawing the map (i.e. adhering to the Voting Right’s act and creating districts that prioritize communities while increasing the number of politically competitive districts) may be hard to execute in real life and is often vague in its description and can leave it open to individual interpretation. Also, not listed in the Blue Book, but the commission’s current makeup would leave out third party representatives.

Cost: Both Amendment Y and Z can slightly increase state revenue from fines collected from lobbyists who don’t disclose the required information. Overall, Amendment Y will increase the state expenditures by $31,479 in the fiscal year of 2020-2021 and $642,745 in the fiscal year of 2021-2022 to fund the commission.

Additional information: Colorado Public Radio has a podcast called Purplish with an episode on both of these amendments whereas at 9News’ Next breaks it down in a segment. Fun Fact: Every member of the state legislature (including Republicans, Democrats and independents) unanimously approved Amendment Y and Z to be on the ballot.

Amendment Z: Legislative Redistricting

What: Amendment Z is very similar to Amendment Y because it proposes nearly the same system as described above for Amendment Y. However, Z deals with legislative redistricting instead of congressional, like Y. Also, the current system for legislative redistricting is different than current congressional redistricting because instead of being decided by the state legislature, this redistricting is done through a reapportionment commission. This current commission is unlike what Y and Z propose because it is appointed by legislative leaders, the Governor, and the Chief Justice of the Colorado Supreme Court and not retired judges. Additionally, the current system doesn’t have the same political checks and balances of Y and Z since up to six of the 11 members may be affiliated with the same political party and politicians and lobbyists aren’t banned from participating. Amendment Z slightly differs from Y because it provides more detail in the criteria section, although the criteria is relatively the same (i.e. must adhere to the Voting Right’s Act, keep cities and counties together, and not dilute the voting power of minorities etc). For the full explanation of the process and application rules, refer to the Blue Book.

NOTE: Pros and Cons for Amendment Z are listed as the same as Amendment Y.

Cost: Both Amendment Y and Z can slightly increase state revenue from fines collected from lobbyists don’t disclose the required information. Overall, Amendment Z will increase the state expenditures by $252,065 in the fiscal year of 2020-2021 and $65,977 in the fiscal year of 2021-2022 to fund the commission.

Additional information: Colorado Public Radio has a podcast called Purplish with an episode on both of these amendments whereas at 9News’ Next breaks it down in a segment.

Amendment A: Prohibit Slavery and Involuntary Servitude

What: Amendment A proposes removing language in Article II, Section 26 in the Colorado Constitution where it says it prohibits slavery and involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for a crime. The measure would remove the exception and make slavery and involuntary servitude illegal in all circumstances (as seen below).

Section 26. Slavery prohibited. There shall never be in this state either slavery or involuntary servitude. except as a punishment for crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.

This amendment should seem familiar to voters since it was on the ballot in 2016. It has been re-worded for 2018 since many agree the 2016 version was confusing and some say it ultimately led to it not being approved.

Pros: The amendment will not leave any room for interpretation that slavery and involuntary servitude can be legal under certain circumstances. In 2016, supporters of the bill said that the removal of the language will not affect the work programs and community services that prisoners are engaged in. They pointed to the fact that half of the states in the US do not have any language related to slavery and involuntary servitude in their constitutions and it does not hinder either prison work or community service programs.

Cons: Opponents say the amendment can be viewed as redundant to what is already in the Colorado constitution. In 2016, the argument was it would create legal uncertainty around prison work programs and community service.

Cost: Amendment A would only have a small financial impact if court filings increase due to offenders filing additional lawsuits.

Additional reading: The Washington Post did a story about the failing of the amendment in 2016

Amendment 73: Funding for Public Schools

What: By increasing the individual income tax rate for those who make over $150,000 per year on a graduated scale, increasing the corporate tax rate at a fixed amount and setting new rates for property taxes in school districts, Amendment 73 will increase funding for preschool through 12 grade. The increased funding will go toward base-per-pupil budgets, gifted and talented programs, special education, paying for kindergarten and pre-school, English language proficiency classes and other areas such as teacher’s salaries.

Pros: Colorado hasn’t been funding public education enough since the Great Recession, resulting in low teacher salaries, cutting certain course offerings and limiting additional services like mental health and counseling. Amendment 73 would provide a sustainable source of funding that is specifically for public education, rather than relying on the state’s general operating budget — which could be used for other programs like transportation, health care or public safety. Though the property tax portion would increase taxes on residential property owners in school districts, it would lower them for business property owners (including farmers and ranchers) who have been paying up to 20 percent more than residential owners for decades.

Cons: Normal methods of funding public education have already been increasing on their own since 2012-13. Increasing taxes imposes restraints and restrictions on individuals without guaranteeing it will improve Colorado’s academic achievement and the amendment does not allow the added taxes to be applied to anything but education. Because the measure doesn’t allow for adjustments for inflation, the future could see excess revenue going to education services that are well-funded rather than going to other sectors that need more money, like transportation.

Cost: Individual income tax rates will be increased on a graduated scale after taxpayers pass $150,000 in annual income. The graduated scale means that a taxpayer will pay five percent for money they make between $150,001 and $200,000, six percent for money they make between the $200,001 to $300,000 bracket, seven percent between $300,001 and $500,000 and eight and a quarter percent for anything over $500,000. For a taxpayer who makes $250,000, they will still only be taxed at the lowest tax rate on income less than $150,000.

Additional reading: For a more in-depth description of how the tax increase will affect you, read this article from The Coloradan. For more information and quotes from proponents and opponents of the amendment, visit this article from Colorado Public Radio (CPR).

Amendment 74: Compensation to Private Property Owners (including Corporations)

What: The full name for this amendment is “Compensation for Reduction in Fair Market Value by Government Law or Regulation” and it looks to change one particular phrase in an existing regulation (Article II, Section 15). Amendment 74 proposes that state or local governments must compensate private property owners if a law or regulation imposed on the private property owner by the government devalues his or her property beyond the fair market value. There are already measures in Colorado that usually offer monetary compensation to property owners in cases where the value or use of the property is lost due to government actions — eminent domain, unintentional damage and regulatory taking. Amendment 74 focuses on expanding the regulatory taking guidelines so that any private property owner who loses fair market value on their property due to government laws or regulations can be compensated by the state. Currently, regulatory taking requires an almost total loss in value or use of the property, but Amendment 74 rephrases that to be “fair market value” to include more cases where government regulation could interfere with a private property owner. An example of this, as provided in the Blue Book, is “if a government limits natural gas development, an owner of the mineral rights could file a claim for the reduced value of his or her property.” The compensation to these private property owners comes from state and local expenditures.

Pros: Coloradans are protective of their private property, and for many, it is the most valuable asset they have. Limiting the potential value of such private property is fundamentally against what many in Colorado believe in, and passing Amendment 74 would ensure that decisions which devalue property, made and enforced by the government, would be paid back to the owner. Current regulations only provide compensation for a total or near-total loss in value of the property, so Amendment 74 would also help to pay back property owners who experience a devaluation but not enough that it’s considered “total.”

Cons: Paying back private property owners from government funds is potentially costly for taxpayers, not to mention unfair. Under these new regulations, large corporations — like oil and gas companies — could receive payouts from taxpayers and governments if governments enact laws and regulations that limit those corporations’ developments. For instance, if Proposition 112 passes (read more about that one below), oil and gas companies can receive payouts for properties that could no longer be developed due to stricter regulations on where they are allowed to drill. In the future, passing Amendment 74 could mean that governments shy away from making decisions that benefit communities, ecosystems or other public resources in order to avoid paying private property owners for their loss in profits.

Cost: The compensation of private property owners would be costly to governments and taxpayers. Most likely, state and local expenditures will increase under this measure.

Additional reading: To read more about the relation between Amendment 74 and Proposition 112, go here. Many local mayors oppose Amendment 74, and this article explains that in more detail. For examples of how other states have dealt with similar measures to Amendment 74, read this article. The Coloradan provides a thorough description of both sides, here.

Amendment 75: Campaign Contributions

What: Amendment 75 is about how much money individuals can contribute to political campaigns. This new measure would increase the amount individuals can contribute by five times the current amount. The goal of this amendment is to even the playing field between wealthy and non-wealthy candidates by allowing them to raise more funds from individuals when facing a wealthy opponent. As a result, this measure only gets enacted if a candidate contributes or loans more than $1 million of his or her own money to directly fund his or her own campaign or to fund a committee supporting or opposing any candidate in the same election. It also applies if this candidate coordinates a third-party to contribute more than $1 million to any committee to influence the candidate’s own election (aka they get their wealthy friends to donate for them). If this occurs, then everyone, including the wealthy candidate, can raise more funds from individuals. If Amendment 75 is passed, individuals could contribute a maximum of $2,000 to $5,750 to a candidate, depending on which race the candidate is in. See the Blue Book for the campaign limits of each race.

Pros: Colorado’s individual contribution limits are some of the lowest in the country. This puts non-wealthy candidates at a disadvantage because candidates do not have a limit on how much they can contribute to their own campaign. As it stands, an individual can pour millions into their own campaign whereas individual donors can only contribute a maximum of $400 to $1,550 (depending on the race) to the person they hope to see elected. Proponents argue this would increase campaign competitiveness by giving less wealthy candidates the ability to raise more money from individual donors.

Cons: Opponents to this measure argue Amendment 75 is not the way to fix financial inequality among candidates because all it does is increase the overall amount of money spent on political campaigns. They argue it also won’t deter wealthy candidates from collecting more money and therefore only inflates the issue across the board.

Cost: If passed, the state’s campaign finance tracking system will need to be modified. This will result in a one-time fee of $15,000 in the fiscal year of 2018-19.

Additional Reading: The Colorado Independent breaks down both sides. It also discusses how this law is particularly interesting since both candidates for governor have spent over $1 million of their own money (Jared Polis has spent a lot). Additionally the Denver Post Editorial Board approves this measure while an ethics watchdog like Peg Perl and Colorado Common Cause (a non-profit for accountability in government) oppose the measure (their opposition is detailed in the aforementioned Colorado Independent piece).

Proposition 109: Bonds for Highway Projects

What: Also known by its shortened title, “Fix Our Damn Roads” (no, we are not kidding about that), Proposition 109 wants voters to approve up to $3.5 billion borrowed money to pay for 66 specific highway projects, with a focus on road and bridge expansion. “Borrowed,” in this case, means that taxes would not be increased to pay for improvements and construction and the revenue would come from the sale of bonds. The proposition also requires the state to find a source to pay back that borrowed money without increasing taxes or fees in the future. The final part of Proposition 109 is a cap on the total repayment amount of the borrowed money, at $5.2 billion over 20 years. If the repayment schedule follows the 20-year timeline, $260 million annually will go toward repayment. This is not the first time voters have been put to the task of figuring out funding for roads — in 1999 a similar proposition was passed for $1.5 billion to pay for 24 transportation projects and was fully repaid by December 2016. However, with Proposition 109, there is still not enough money to fund all 66 projects, so an 11-member commission will prioritize the list.

Pros: Highways have become one of the core functions of government — and that includes maintaining existing ones and building new ones. With Proposition 109, the 66 most essential projects will be prioritized by the state government without raising taxes or fees. Not only will this lessen the burden on the individual financially, but it will also improve the quality of people’s commutes. Traffic congestion is becoming more of a problem and this proposition is aimed at improving highway capacity for individual drivers.

Cons: For the last two years, the state has already passed two laws to increase funding for transportation projects. Between the sale and lease-back of state buildings and other state revenues, there is already $2.5 billion going toward infrastructure. If Proposition 109 passes, that $2.5 billion will be replaced with borrowed money, ultimately putting $1.7 billion in taxpayer money toward interest payments. The proposition also doesn’t address ongoing maintenance costs of the 66 projects, doesn’t cover the cost of all 66 projects and doesn’t put any money toward other forms of transportation — like bus, bike or rail.

Cost: It will ultimately cost $2.95 billion. Although revenues to the state will increase in the short-term (through the sales of bonds), the long-term financial commitment (repaying the borrowed money) will cost more.

Additional reading: See the list of proposed highway projects here, starting on page three. Read this article in Westword about the man behind Proposition 109 and why he thinks it’s so important to pass.

Proposition 110: Sales Tax and Bonds for Highway Projects

What: Proposition 110 is a second transportation-based measure on the ballot this year, but this one is different from Proposition 109 in a few ways, the major one being that it raises taxes in order to fund transportation projects. If the proposition passes, the state’s sales and use tax will be raised from 2.9 percent to 3.52 percent for 20 years. Like Proposition 109, 110 also would borrow money through transportation revenue bonds. The difference there is that Proposition 110 wants to borrow $6 billion rather than the $3.5 billion in Proposition 109. The revenue generated from increased taxes and borrowed money would be distributed to transportation projects to the state (40 percent), local governments (45 percent) and to multimodal projects (i.e. bike, pedestrian, bus and rail — 15 percent). Proposition 110 is also different from 109 in that it includes a budget for those multimodal projects and does not have a specific list of highway projects to be worked on.

Pros: Although this proposition raises taxes, it does so to benefit the people who are paying them. Highway maintenance and development is key to improving the quality of living, especially in the Front Range, and Proposition 110 provides a sustainable source of revenue to tackle those projects. It also puts more power in the hands of local governments to decide which projects are to be prioritized. With more people moving to Colorado and increasing the number of cars and commuters, the added tax collected from their purchases can help maintain the roads for everyone.

Cons: Not only does this measure increase taxes, but it also resorts to borrowing money through the sale of bonds — and with more borrowed money than Proposition 109. This will put taxpayers at a disadvantage over the next 20 years in two ways. Plus, the sales tax in Colorado is already high — in some areas exceeding 10 percent — and increasing that would put more of a strain on existing residents. Many also argue that raising sales tax disproportionately affects low-income households.

Cost: This will cost the taxpayer since the sales and use tax will increase by 0.62 percent. For a household earning approximately $42,000 annually, they will pay almost $100 more in sales taxes each year (depending on the total amount of money they spend on their purchases).

Additional reading: Since Proposition 110 is very similar to 109, this article gives a better idea of where the two different measures originated from and who (or which companies) have been financing them. Check out this site from Commuting Solutions if you want to understand where Proposition 110’s money will go if passed. KUNC also provides this well-balanced synopsis of the differences between Proposition 109 and 110.

Proposition 111: Limitations on Payday Loans

What: Proposition 111 focuses on reducing the annual percentage rate (APR) allowed on payday loans. Payday loans are small, short-term loans that are easy to access (most payday loan places have easily accessible storefronts). Under Colorado law, payday loans can be no more than $500 with a minimum repayment term of six months, no maximum repayment term and do not have a penalty for early repayment. In 2016, it was estimated that the average APR of a payday loan was 129 percent. Proposition 111 would cap that APR rate at 36 percent. The measure would also ban payday lenders from offering higher cost loans via the mail, email, the internet or telemarketing — regardless of if they have a physical location in Colorado or not.

Pros: Proponents argue that payday loans are predatory and create a cycle of debt by creating unreasonable terms with some loans having rates of 180 percent APR. By reducing the APR of payday loans to 36 percent, it would allow Coloradans to repay their loans and get out of debt.

Cons: Opponents argue that lowering the APR will get rid of payday loans altogether in Colorado. This will drive people to incur other debts by not being able to pay their bills on time. This would lead to late payment fees, bounced checks, overdraft fees and more. Also, opponents argue that Colorado has done a good job to regulate payday lenders in the past by passing reforms in 2010 and 2007. As a result, they have created a more fair market than many other states. If payday lenders are eliminated it will open the market back up to unregulated lenders who will likely charge higher fees.

Cost: If Proposition 111 gets rid of payday lenders, these lenders will not renew their licenses and therefore will not pay fees to the Department of Law.

Additional reading: Colorado Public Radio has a great on-air segment that fact checks both sides and reveals the complex nature of this proposition. Go here to read The Sentinel’s approval of the proposition and here for the Greeley Tribune’s opposition.

Proposition 112: Oil and Natural Gas Development

What: If Proposition 112 passes, new oil and natural gas development will be pushed farther away from occupied structures, water sources and areas considered “vulnerable” than current regulations require. The new measurement would require 2,500 feet between those spaces and new development — across the board. At this time, oil and natural gas developers must be 1,000 feet away from high-density buildings like schools, hospitals and neighborhoods with more than 22 buildings, 500 feet from homes and 350 feet from “vulnerable” areas like playgrounds, lakes, streams and drinking water sources. Oil and natural gas development includes drilling, production and processing of oil or natural gas as well as the highly controversial hydraulic fracturing — or “fracking.” This proposition does not apply to federal land, such as national parks and forests.

Pros: In the past five years, northern Colorado has experienced both an increase in residents and an increase in oil and natural gas development. If Proposition 112 passes, residents can feel more assured knowing their homes and businesses will not be taken over or polluted by rampant development. Already existing oil and natural gas operations have negatively impacted the health and quality of life of some residents, who have reported things like sinus and respiratory conditions, headaches and nausea. Proponents to this measure also feel that protecting water sources and “vulnerable” areas are a top priority in Colorado and without strict regulations, the oil and natural gas industry will not do their due diligence in protecting them.

Cons: According to the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC), over 80 percent of non-federal land in Colorado would be excluded from development if Proposition 112 passes. This could negatively impact the number of jobs directly related to oil and natural gas development as well as related industries that have benefited from the increase in production over the last few years. In 2017, roughly $10.9 billion was generated through oil and gas development and the fear is that Proposition 112 will not only stall that growth, but stop it completely. Opponents also feel that existing regulations are sufficient, especially since the original distance requirements were made with the consideration of the concerns of residents.

Cost: Although there is no financial cost to residents with the passing of this proposition, the state government, the Department of Natural Resources and local governments anticipate a reduction in revenue. Since producing well sites pay higher taxes, reducing the amount of land that can have well sites will reduce the amount of revenue collected, leading to the decreased funding of certain programs like low-income energy assistance, control of invasive species and water supply project grants.

Additional reading: To find out more about both sides, including quotes from well-known opponents and proponents, visit this page. And to find out more about the truth behind some of the ads you may be seeing on TV and in other advertising, read this article. For more information about the reasoning behind the new distance regulation request, read this article from The Coloradan.