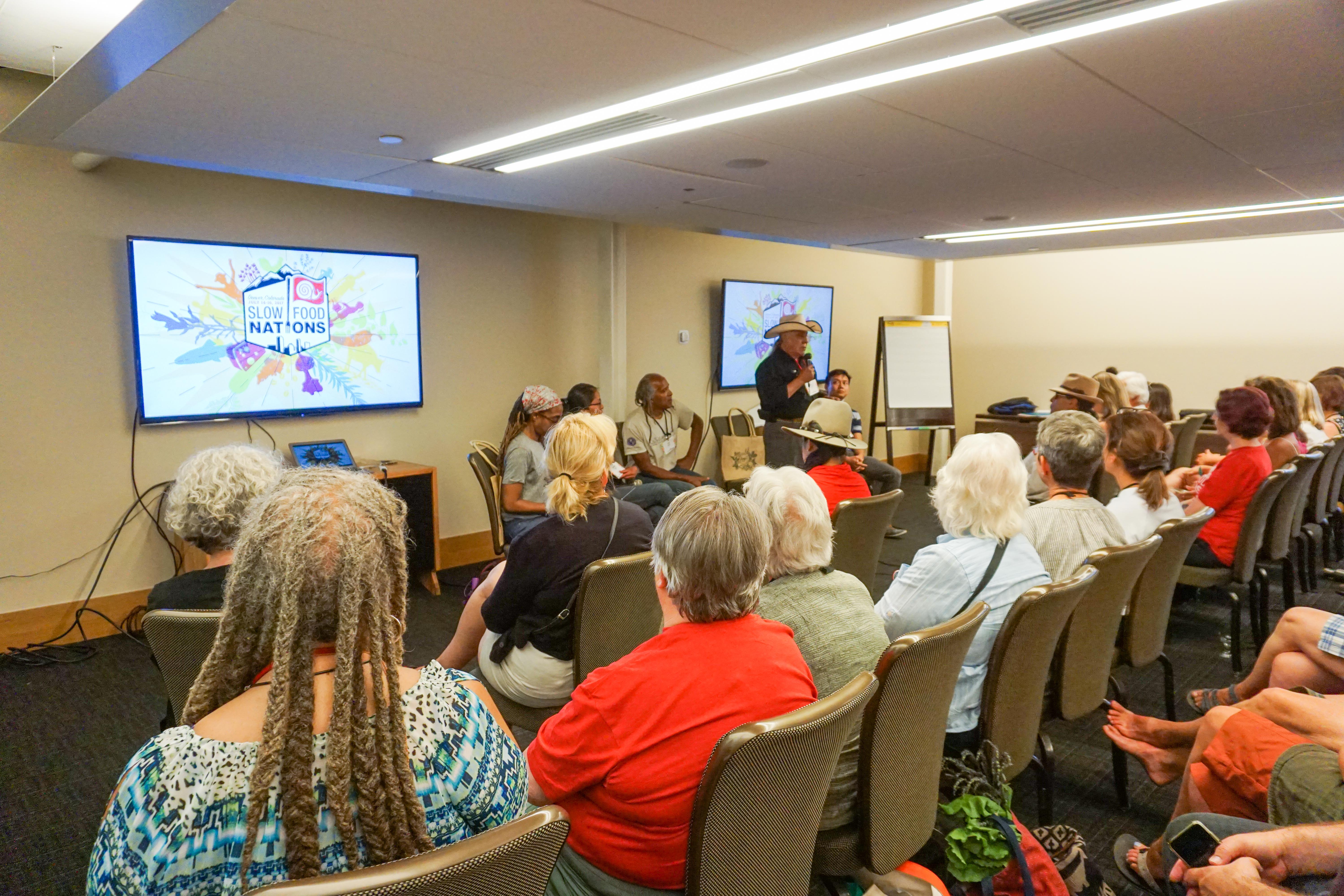

Slow Food Nations has finally come and gone. The highly anticipated three-day food event fulfilled its promise to be the epicenter of the culinary world with its jammed packed schedule of programming and influential guests from all over the world. But for most Denver dwellers, it’s likely you may have only seen it in passing or attended the Taste Market (we don’t blame you, all that free cheese was alluring). If so, you missed out on one of the most important aspects of Slow Food — the educational component. Dozens of speakers, including culinary icon and activist Alice Waters, spoke about the impact of the food world and its future. We attended as many of these talks as possible to bring you the most essential and/or fascinating aspects of what you missed. Here’s what we learned:

#1. Lunch should be an academic subject

One of the biggest events of the Delegate Summit on Friday, July 14 was the lunch with Mrs. Waters. The chef, who’s known for starting the original farm-t0-table restaurant Chez Panisse, is one of the most well-known advocates for improving school lunches through The Edible School Yard Project. Waters believes turning the lunch hour into a part of education will help students make better food choices that are “healthy for them, their communities, and the environment.” This means that students will take time of out lunch to work in school gardens and learn about nutrition while incorporating subjects such as math and science. Outside of Waters Foundation, groups like Whole Kids were present during the weekend to talk about how the organization is helping train teachers and providing grants through Whole Foods to fund school gardens.

To demonstrate how efficient her program can be, Waters teamed up with local school kids to feed over 500 people during her talk at the Delegate Summit. The team of kids and teachers served beans, squash and corn as an extension of their lesson on Mexico and the Los Tres Hermanas way of farming. In under five minutes, the entire audience of 500 was served the delicious and wholesome meal using an improved lunchroom serving method that puts an emphasis on teamwork. At each table, every individual “student” was instructed to retrieve a food item for the meal at serving stations, while two set the table. The result was a rather impressive and satiating lesson.

#2. Chefs can be important political actors

Following suit with Water’s demonstration was a discussion with the James Beard Foundation (JBF). Lead by Katherine Miller, policy director at JBF, she explained that chefs are the perfect political actors. Often they represent important sectors as both small business owners and consumers while also being community leaders. As a result, chefs are in a unique position to represent their communities politically when it comes to food and nutrition. She drove this home by explaining most Americans trust the food and beverage industry over the financial and energy sectors of the US. Even more so, the JBF found that 74 percent of Americans believe the food and beverage industry should be more active in the debate over solutions to food and nutrition policy. Miller then introduced the JBF’s initiative to train chefs to become more politically active through a policy boot camp. Influential chefs such as Sean Brock, Tom Colicchio and Hugh Acheson have all attended the camp and have made steps towards improving food policy. Outside of JBF, other Denver chefs, like Adam Schlegel co-founder of Snooze, president of EatDenver, are proving that leaders in the food industry can make a difference. Schlegel explained he has submitted a grant to the city of Denver with hopes of subsidizing compost around the city. “We feel like it’s a great gateway drug for restaurants,” said Schlegel.

#3. Restaurants want to improve sustainability, but not at the expense of the diner experience.

One of the ancillary things we learned at Slow Food is while the intention of Slow Food is clear, the execution is sometimes muddy. This was swiftly demonstrated at the talk “Waste Not: The Endless Unsustainability of Restaurants” moderated by Christine Muhlke, executive editor of Bon Appétit on Sunday morning. The round table brought together chefs and editors to discuss the problem of waste and unsustainability in the kitchen.

“Not everyone comes to a restaurant begging to learn about sustainable waste,” Chris Ying, former editor of Lucky Peach explained. “And none of us think any of this should come at the expense of a restaurant being great.”

James Beard award-winning chef Steven Satterfield agreed. He built his Atlanta restaurant around sustainable practices, and he said the team is “always looking for ways to turn waste into flavor.” But, he’s not serving a side of activism with every meal at Miller Union. He said that sometimes he decides to tell the food waste story behind his dishes, and other times he leaves it alone.

“We started with sustainability in mind. We said, ‘This is how we’ve always done it. It’s how we’re going to do it. It’s Miller Union 101,'” Satterfield said, “…but I prefer to discuss this in [an environment like Slow Food Nations]— not in the dining room. In a lot of cases, people just want to have great food.”

He does, however, find other places to spread his sustainable ideas— in the kitchen and on social media.

“I can reach so many more people with these messages through something like Instagram… those things are really powerful tools… There are still ways we can share our stories that can reach a lot of people.”

This message was clearly controversial and somewhat contradictory to other panels. These chefs said while sustainability is important, it doesn’t take first-chair to running a profitable business or serving top-notch food. One audience member even voiced that they wished restaurants were more involved (hello, 74 percent?)—but according to the chefs, this is not the sentiment of most of the diners they encounter.

#4 – Restaurants Need Diners to Demand Sustainable Food Choices

The restaurant business is a people-pleasing one. It’s no secret that running a restaurant is hard and margins are thin. As a result, restaurants are often tied to the desires of its diners in order to survive— no matter what they may be.

Many Slow Food activists noted that the best way diners can help is to express their desires for a more sustainable food system whenever possible— to politicians, to restaurants, to the media and with their dollars. Otherwise, change can never happen fully.

“It’s never going to solely be the restaurant’s job [to make sustainable choices]. As diners, our actions aren’t limited to what we do in that restaurant,” Ying explained. “We— as diners, consumers, eaters— need to represent a powerful block of people.”

Ying used last year’s sensation—Pokémon Go— as an example. When it was soaring in popularity, websites like Yelp responded by adding categories to denote restaurants that doubled as PokeStops. He hopes the same will happen with sustainability. By raising consumer demand for food to not be wasted, restaurants and companies will follow suit. He said he’ll be satisfied to see a “sustainable” category on review sites like Yelp someday.

“You have to say you want it to make something worth a restaurant’s (or company’s) while… You have to get consumers excited about it. Diners don’t necessarily make food decisions based on that yet. I don’t know how [many] people are coming to restaurants because they’re sustainable or not, right now.”

#5. The US Food System is Not Equal

Professor Angela Harris opened her talked with an interesting but pertinent factoid, “80 percent of US farmers are white men.” The former law professor UC Davis School of Law was quoting a study recently conducted by the USDA as a way to drive home the inequity in today’s food system. Harris’ argument was underpinned by the theory that the plantation system has not receded into history. Rather, the same system, one that was propped up by the exploitation of disenfranchised brown and black people, still continues today. But now it is primarily seen with underpaid and overworked migrant workers from Mexico and Central American. “Today the question is more about being undocumented or not,” she explained. Harris also explained that the corporatization of farming is also a remnant of the plantation system since it centralizes the production and makes it nearly impossible for independent farms to compete. “All farmers of all colors are under the thumb of this transform plantation system,” she said.

Harris’ talk, while rooted in the history of farming in America concisely showcased that while slavery has been abolished in the US, the remnants of its power structures still remain influential in today’s food system.

—

With a weekend jammed packed with learning opportunities, there are plenty of moments we were unable to attend. Luckily the event is set to return next year. Make sure to mark your calendar for next summer, and come hungry for some knowledge.

All photography by Brittany Werges.