If you’ve driven by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in the last few weeks, you may have noticed the exterior being transformed with a giant mural made of vinyl sticker material. This is the work of artist Cleon Peterson and is indicative of the immensity of the newest three exhibitions within the museum. Opened February 3 to the public, Peterson’s show Shadow of Men is alongside Diego Rodriguez-Warner’s Honestly Lying and Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, the Message is Death. The three exhibitions address questions about modernity while using archetypes, psychology and historical imagery.

One of the most rewarding aspects of the MCA’s exhibitions is their ability to bring relevant art from separate artists together under one roof and have those artworks enrich and aggrandize each other. Another MCA cornerstone is displaying art that may seem shocking to some, but hastens and fuels the conversations that artists and art lovers live for— namely, how to navigate through life in a way that’s both beautiful and meaningful. The curators and organizers at the museum have outdone themselves this time, with a collection of art that will not only encourage dialogue but will leave visitors in awe.

These three artists each have their own techniques, and the resulting creations are so different it’s hard to believe at first glance that there could be many similarities. But the common denominator is their use of preestablished symbolism to convey wholly authentic artworks. Universal ideas about empathy and compassion on one side and violence and fear on the other elevate these artists and their creations into an almost philosophical realm. As viewers, taking in these big conceptual messages will require some inward focus and there is no guarantee that the internal landscape you arrive at will be a happy place. But art has to take chances sometimes, and when artists allow those risky moves to happen and evolve in their practices, we are given the opportunity to see truly original work. Take a few hours to visit these exhibitions— they are fascinating, frightening and compel us to find our own truth even if that’s only because we’ve beholden the truths of the artists first.

Diego Rodriguez-Warner

Rodriguez-Warner grew up in Denver, though he was born in Nicaragua. His exhibition, Honestly Lying at the MCA is his first museum show and also the first comprehensive display of his work over the last five years. Using a technique he’s developed after years of fine art education through Hampshire College and the Rhode Island School of Design — as well as training to be a printmaker in Havana, Cuba— Rodriguez-Warner paints and carves onto large plywood panels, creating abstract landscapes that burst with color and are sprinkled with historical imagery.

Honestly Lying is showcased on the main level of the museum and is best started with the salon-style wall with 14 hanging pieces. These exemplify Rodriguez-Warner’s evolution from traditional woodblock printing — where the negative areas of an image are carved out and applied with ink in order to imprint on paper — to his own unique style where he takes out the step of transferring a woodblock to paper and experiments with the image using several painting mediums and a collage aesthetic. The salon-style wall also provides a more cohesive idea of the artist’s use of historical images, especially Asian figures, than the more abstract pieces in the rest of exhibition.

His original influences when he began this body of work were steeped in Latin American culture, where printmaking was as political as it was artistic. While in graduate school, Rodriguez-Warner became disillusioned by the pretense that artists should constantly create original imagery, leading him to re-use images like a female nude, any body parts, flowers and other visual tropes that are constantly showing up in historical art. In order to demonstrate this process, Rodriguez-Warner provided an example of his maquette board— a piece of foam he pins images to, creating a collage that can always change without gluing anything down— in the second room of the exhibition. The maquette board brings to mind a Milagro or a little shrine, and Rodriguez-Warner calls it his “Archive of Gestures.” He then takes a photograph of a section of his maquette board and recreates it on plywood panels, complete with the shadows that appear from pinning down the paper fragments rather than using adhesives. On the opposite wall of the maquette board, Gestures is one of the few pieces that directly represents this transfer and allows the viewer to better understand his technique.

What makes Rodriguez-Warner’s work so impactful is his ability to use historical references to confront modern problems. Unlike some of his peers, who critique the digital world with digital or technological practices, Rodriguez-Warner uses older techniques and imagery to convey contemporary issues. It works because we have an entrenched symbolism that is easily translatable between cultures and speaks to us on an almost primal level.

In the corner gallery, his reconstruction of the famous ukiyo-e Japanese woodblock prints immediately tells a story that is understood based on instinct rather than knowledge or explanation. Because his pieces are composed of many layers — from spray painted striations, to woodblock relief carving, to acrylic, oil and latex painting — the viewers can stare at one for a long time and still notice new points of interest or beauty. Rodriguez-Warner, through these processes, is both a deconstructionist and reconstructionist. And it’s because of his surgery on historical images that he is able to convey a deep and critical view of society and the human condition while moving away from realistic portrayals of life.

The final room is composed of pieces made most recently by Rodriguez-Warner (some being finished within weeks of the opening of this show). Even this early in his career, he is already experimenting with his technique and is quickly inventing his own artistic vocabulary that is most apparent in this final group of works. His desire to take apart scenes or ideas and put them back together in a novel way is becoming more cohesive and therefore more impactful, leaving viewers with the sense that Rodriguez-Warner might be one of the best artists of our time.

Honestly Lying was curated by Zoe Larkins and will be on display until May 13, 2018.

Cleon Peterson

From Seattle, Peterson’s life has been fraught with struggles — from a turbulent home life to an addiction to heroin and eventually jail time. Though he’s been a prolific artist since his adolescence, displaying gallery exhibitions beginning when he was 15, Peterson’s path veered away from creating for a period of time— a lapse that eventually informed his subject matter that is now showcased at the museum. His exhibition, on the second level, is not for the faint of heart. Shadow of Men— to put it simply and unequivocally— is violent. Although the violence is portrayed with artistic mastery, each and every piece in the exhibition depicts an aggressive act that is representative of Peterson’s personal unrest. Best framed by the ideologies of Carl Jung, Friedrich Nietzsche and more contemporary work from writers like Chuck Palahniuk (Fight Club) and Anthony Burgess (A Clockwork Orange), Shadow of Men asks the viewer to bear witness to the internal struggle between good and evil, light and dark, the shadow self and the conscious self.

The show begins with a quote from Jung— “everyone carries a shadow and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is.” With this in mind, the viewer is taken on a journey into the darkness of the artist’s thoughts, revealing a story about conflict, resentment, abandonment and questioning whether our moral compasses are as reliable as we like to think.

More than anything, this exhibition is a personal narrative from Peterson, which is why you’ll find quotes from the artist throughout. Insights like “I’m not trying to document a specific situation or an actual event. It’s more like I’m painting the essence of violence— the power dynamics, victimization, victimizers. It reaches beyond my own personal experiences to the experience of how we all live in the world today, where war, terrorism, shootings, police brutality, and other forms of violence are woven into the fabric of society.” Some of them are so personal, they read more like a journal entry than an explanation.

This show represents what Peterson has been working on since 2006 and primarily uses three tones of acrylic paint— white, black and beige— on varying sizes of canvas. His previous experience with graphic design is immediately apparent, with balanced compositions that are visually pleasing, even when you see the disturbing nature of the acts being portrayed. The first room contains a handful of paintings accompanied by small porcelain sculptures (a new addition to Peterson’s repertoire).

Between the first room and the central room, the piece Endless Sleep introduces viewers to Peterson’s inspiration from Western Classical and Greco-Roman art, especially vases that illustrated daily life. By referencing this historical style, Peterson aims to document his daily struggles within contemporary society much like the toil of an ancient worker or the strife of an ancient serf might have been captured on pottery in the past. This ability of Peterson’s to express such existential internal friction through relatively simple imagery will make his art timeless.

The remaining three rooms in the exhibition are dominated by immense paintings and sculptures, filled with authentic expressions of anger, angst, violence and various atrocities. The significance of each painting is framed by the fact that it is the powerful acting on the powerless. Every aggressor is black— a representation of the shadow self— and the victims are white or beige— the embodiment of innocence. Within the current race consciousness, this might seem upsetting, but it is important to remember that Peterson’s choice of black and white is about the spiritual definitions of the colors, not about skin tone.

“We all want artists to open up to us, but we want them to show us something beautiful. I wanted to exhibit his work because I’ve never met a man who so honestly and transparently wanted to talk about male violence,” the curator for this exhibition Adam Lerner explained. “He’s opened up and he’s showing an ugly side, but more than that, he’s showing the ugly underbelly of society. We are missing that in our culture right now — to look at something that is actually representative of us at this time in history.”

There is no easy way to digest Peterson’s work. Unlike the artsy violence of Tarantino or the cartoonish gore of action films, Peterson delivers a body of work that both embodies the daily violence of living and the grandiose battle between enlightenment and giving into your own darkness.

Shadow of Men was curated by Adam Lerner and will be on display until May 27, 2018.

Arthur Jafa

Best known for his work in Hollywood and with music videos for big-name stars, Jafa made his first foray into the art (for art’s sake) world with the roughly eight-minute video displayed on the bottom level of the MCA in the Whole Room Gallery. The video, titled Love is the Message, the Message is Death, was first released by Jafa in 2016. Set to Kanye West’s “Ultralight Beam,” the video plays a montage of internet clips— from footage of a policeman’s dash camera to cell-phone confessionals, to videos of black musicians performing. Because most of the footage is sourced from the internet, much of it seems or is familiar, though this lends to the overall impact of the video rather than detracting from it. The combination of the gospel-like sounds from West’s song and the sometimes disturbing visuals should incite goosebumps on anyone.

Jafa has a lot of experience in cinema, working as a cinematographer in films like Daughters of the Dust and Crooklyn. It was when he worked on Beyoncé’s visual album Lemonade that he gained more attention as an artistic filmmaker. He’s also worked with Solange Knowles and Jay Z, leading to his interest in the intersection of black music and black cinema.

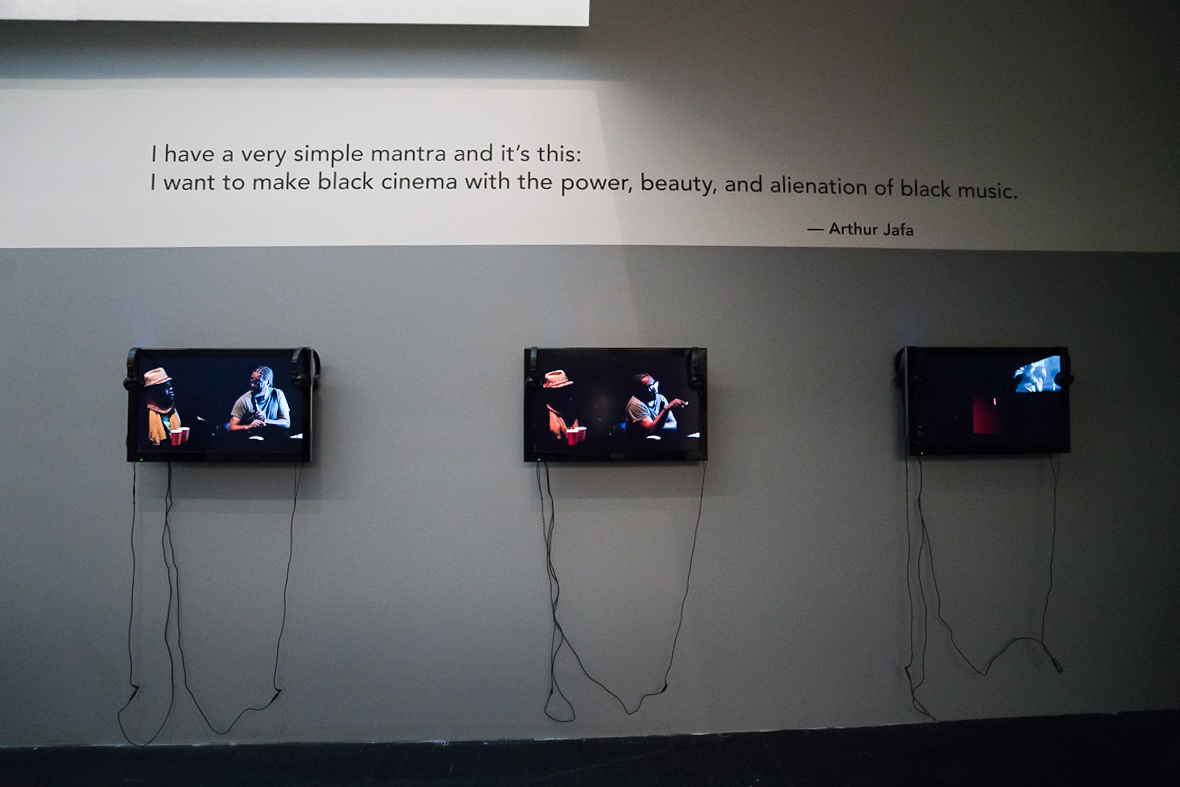

“I have a very simple mantra. I want to make black cinema with the power, beauty, and alienation of black music,” reads the quote by Jafa directly outside the Whole Room Gallery. Underneath this quote there are three television sets with headphones where you can listen to Jafa speak about the selection of clips for Love is the Message, the Message is Death with an expert on black cinema, Gret Tate. This interview reveals Jafa’s innate humor and impressive knowledge on several different subjects and provides a more complex foundation to understand his video.

More than a conversation about race or privilege or anything as political as that, Love is the Message, the Message is Death speaks to the idea of empathy. Can you put aside your own wants, desires and preconceived notions in order to step in the shoes of someone else? Can you understand the plight of another individual without wanting something in return? In these questions, there is an obvious critique on the media, on the portrayal of what black life is in America by both the news media and Hollywood media. But there is also a hope that empathy exists, even if we have to usher people toward achieving it.

Love is the Message, the Message is Death was curated by Zoe Larkins and will be on display until May 13, 2018.

All photography by Meg O’Neill unless otherwise noted.

Great write-up!