“The South’s got somethin’ to say,” proclaimed André 3000 when Outkast won Best New Rap Group at the 1995 Source Awards. The statement came amid boos from his East Coast and West Coast peers, and it inspired a generation of Southern artists.

This is what Valerie Cassel Olivier, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts curator, intended to put forward with the exhibition “The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture and the Sonic Impulse.” The exhibition mixes sight and sound to explore the deep richness of Black culture in the South through a musical lens.

“The South is a gateway to our understanding of America. This is a journey that underscores that there is not a monolith,” Oliver said. “[The term ‘Dirty South’] is multi-layered and that is the beauty of it.”

In the mid-90s, the southern hip-hop scene claimed the term “Dirty South” as a regional term of endearment and used it as a badge of honor. The exhibition, organized by Oliver and currently displayed at MCA Denver, claims the term as neutral evidence of the South’s existence. It’s not just the good or the bad. It is its grit, the resilience, the shadows where we don’t dare to shine the light. ‘The Dirty South’ is simply here, present and ever-evolving.

The “Dirty South” takes over the three floors of the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, featuring the works of over 80 artists in a variety of genres, from sculpture and painting to photography and film, as well as large-scale installation work. The sounds that echo through the building are the soundtrack that threads the exhibition in unison.

Landscape

The show starts in the museum’s lobby with the sounds of water calling you into the gallery with the first theme – Landscape. The art pieces on this level acknowledge the influence of the South not just as a source of the culture, but as an eternal inspiration that emanates from the land itself.

We are greeted with the visual-sonic piece “Wacissa” by Allison Janae Hamilton. The sound and images of flowing water from the video serve as a type of baptism, preparing us for what we are about experience. For this piece, Hamilton films from behind a boat as she navigates the Wascissa River in rural Florida. The channels of the river were originally dug by enslaved Black people to serve for the transport of cotton. The distorted sounds of being underwater combined with the upside-down perspective of the camera provoke a sense of unease and confusion. You are one with the vessel but certainly not a passenger or the captain. As the introduction point in the show, Wacissa reminds us of the initial passage of enslaved Black people in America, without their consent and command.

The sound of the Black South is ever-present even when there is silence. “Take it to the Bridge” contains a twisted, long stick that connects from an African vase to a vintage record player. Along with a string of African beads, the stick not only bridges the two continents, but also the past and the present, sturdy enough to carry the sounds and history of the African cultures.

Without delay, we get a sense of a history of endless oppression countered with creativity in which art and sound are complementary tools of survival and resistance.

Sinners and Saints

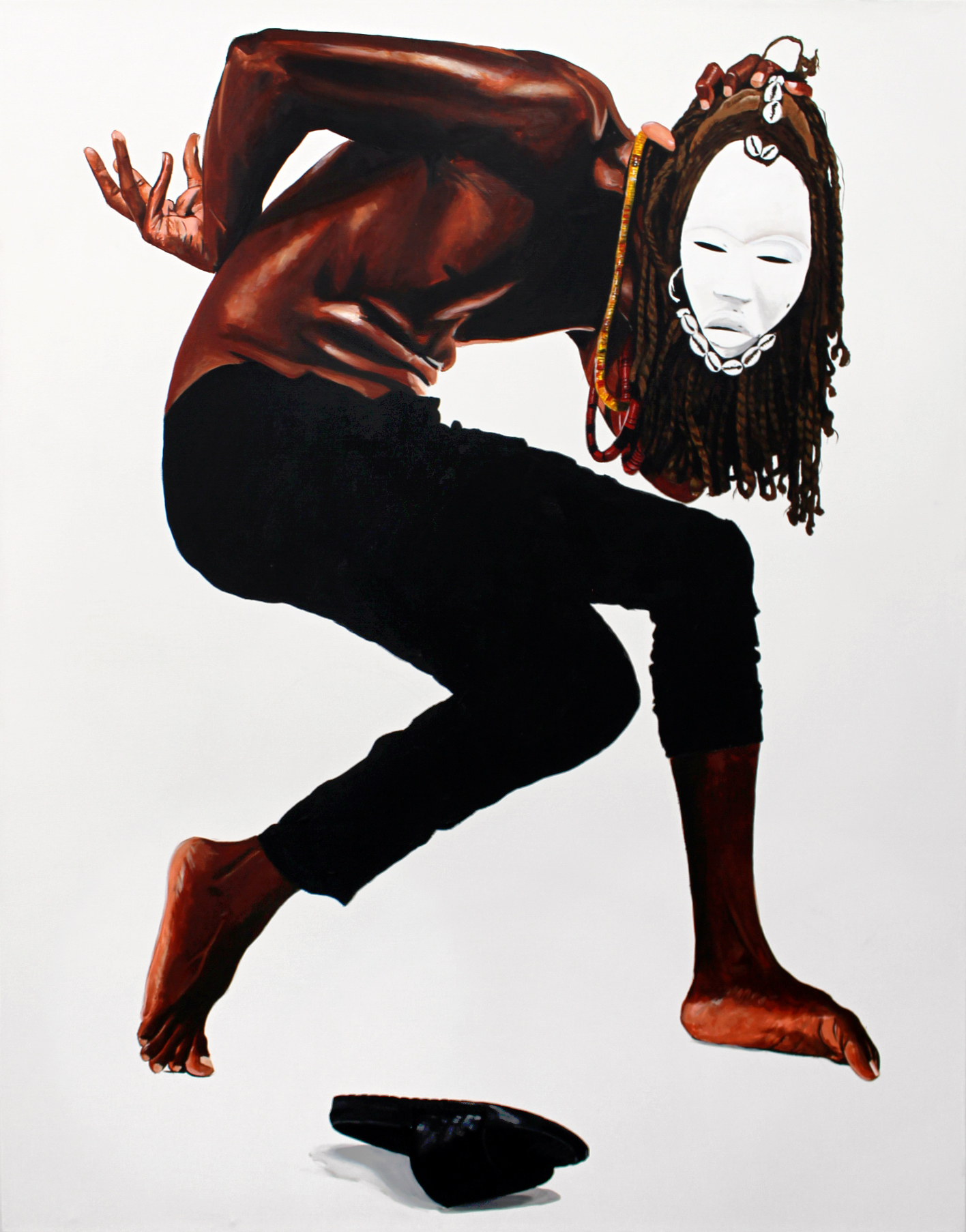

The second part of the show is devoted to images of the spirituality that permeates Southern culture. A shirtless black man in a white mask adorned with cowrie shells engages in a dynamic pose in “Dobale to Spirit” by Dr. Fahamu Pecou. A single flip-flop rests sideways in front of the figure. Even though the unknown man is crouched, the pose has a fluidity of movement that demonstrates powerful energy.

Additionally, you will find architectural pieces in Sinners and Saints like Rodney McMillian’s red chapel made out of stitched vinyl. “From Asterisks in Dockery” serves as a walk-in version of a chapel that once stood in Mississippi where many well-known blues musicians would seek shelter and work as they passed by.

Black Corporality

The theme of the show’s third section — Black Corporality — explores the Black body as a vessel of tradition, generational trauma and resistance, and knowledge.

You will find impactful sonic pieces like “King of Arms” by Rashaad Newsome, a video that showcases traditions of procession and theater. The work pays homage to many performative arts rooted in Black culture, from Mardi Gras festivities to hip-hop music to vogueing, an iconic dance from the gay ballroom scene. Themes of royalty, excellence and joy resonate through the video as Newsome crowns himself king by the end.

Other installations evoke darker emotions. Nadine Robinson’s “Coronation: Organon” is a sonic sculpture inspired by 1963 Project C, a demonstration against segregation where a thousand demonstrators were attacked by dogs and fire-hosed by police. The piece is made of 30 speakers stacked in the shape of Atlanta’s historic Ebenezer Baptist Church where Martin Luther King Jr. was the co-pastor. Initially, you will hear a fragment of a coronation anthem by German composer George Frideric Handel. Then, a mixture of historical sound clips creates a menacing cacophony. You will hear barking dogs, the force of water, as well as pieces of sermons, choral music and protests.

Additional work in this section will leave you unsettled like “In Mississipi” which portrays real ads by enslaved Black people, recently freed, looking for their relatives; and “Hers (Lynching Fragments series)” by Melvin Edwards, a welded steel sculpture that evokes a gruesome, brutal image of the South’s dark history of lynching.

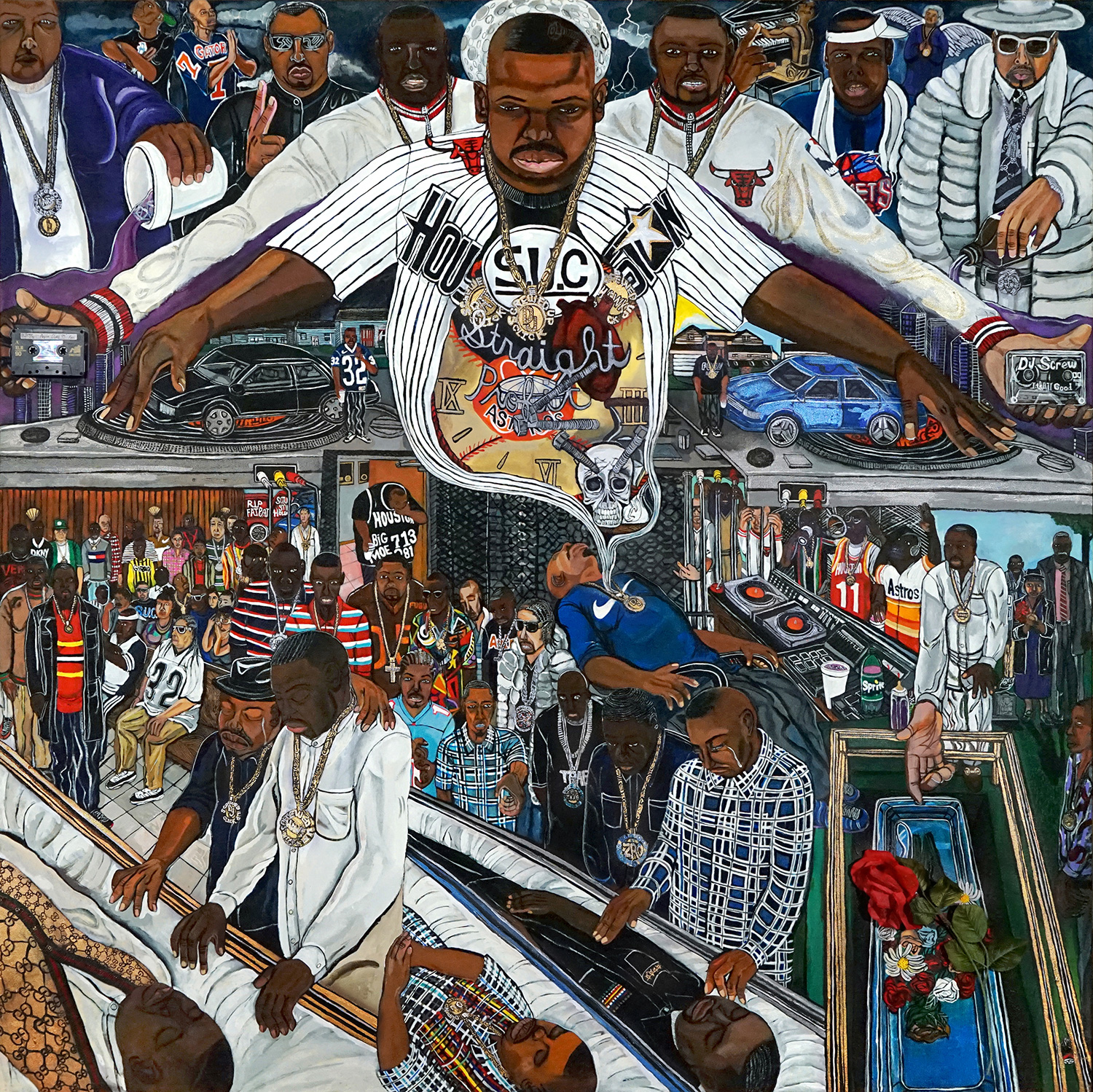

Finally, the show provides a Cabinet of Wonders to showcase the South’s influence on the hip-hop scene and other musical genres. With iconic wardrobe pieces made for James Brown and Ceelo Green, DJ Screw’s tapes and other musical artifacts, the final section shows just a glimpse of the South’s impact on music history.

The term “Dirty South” takes on many meanings as the exhibition progresses. Sometimes it can joyful. Sometimes it can be conflicting and at other times it is a reality that is simply unbearable. Whatever the lingering feeling, “The Dirty South” shows its deep roots not only in Southern history but in the nation’s history. Through impactful imagery, texture and sound, the South undeniably has and will always have something to say.

“The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse” is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver until Feb. 5, 2023. For more information on the exhibition, visit MCA Denver’s website.