Sustainability is a cornerstone issue for Denver and its citizens. As we look ahead at a future where climate change will impact every one of us, we want to give a platform to the people and groups spearheading sustainability efforts in the Mile High City. In this sustainability series, we will discuss the problems, explore the solutions, track the efforts and explain how to develop better sustainable practices in daily life. Go here for our first article.

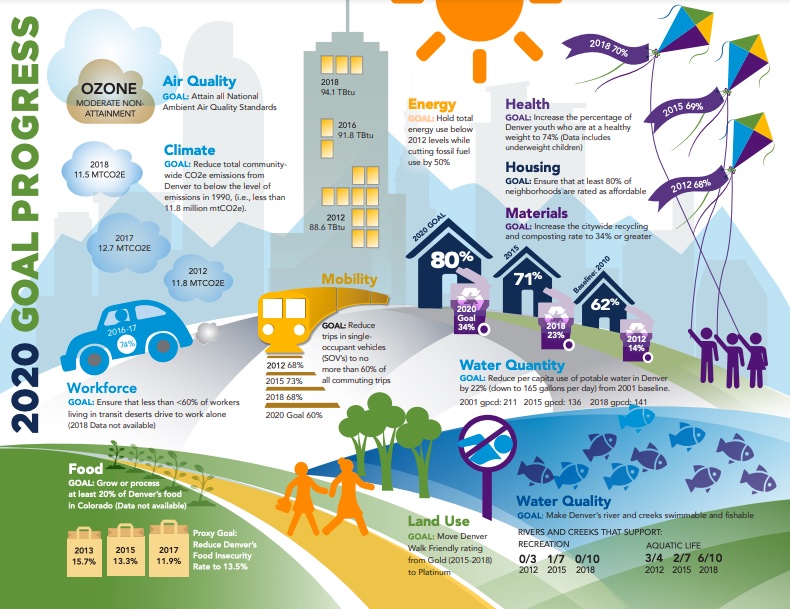

Twelve categories were created in 2014 as the baseline for sustainability goals for the City of Denver — air quality, climate, energy, food, health, housing, land use, materials, mobility, water quality, water quantity and workforce. Each category included a target to reach by 2020, for the community at large and for government operations.

As we start a new decade, it’s important to take inventory of the 2020 goals we’ve achieved and what we still need to work on in order to reach the next benchmarks, which were laid out in a new set of guidelines extending to 2050 called the 80×50 climate action plan. But, based on our achievements thus far, it’s obvious that in the coming years, transformational changes in the way the city operates, in the way citizens live and act, and in the way businesses are regulated or operate will be required.

Sustainability Goals Met

The only reportedly achieved community standard 2020 sustainability goals are water quantity and climate. The climate goal aimed for carbon dioxide emissions below 1990 levels, which was actually accomplished in 2018. And the climate goals in the 80×50 climate action plan adopted in 2018 — to reduce carbon dioxide emissions 20% from a 2005 baseline— were achieved a year early in 2019. Both of these are big wins, although Grace Rink, the new Denver Chief Climate Officer and director of the office of Climate Action, Sustainability and Resilience (CASR), attributed some of this improvement to Xcel Energy’s clean energy transition, which involves decarbonizing its grid, adding renewables and reducing emissions through other means. Xcel’s individual goal, to be 100% carbon-free by 2050 and 80% less carbon by 2030, reportedly came from a 2019 state law.

The water quantity 2020 goal was to reduce the per-person use of potable water by 22% of 2001 levels (down to 165 gallons per day). To put that in perspective, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), each person in a house uses 80 to 100 gallons of water per day on average to flush the toilet, take showers and baths and for other water uses. Over the last 15 years, Denver Water has been working on water conservation programs (following a large drought in 2002-2003) that “permanently changed behaviors around irrigation and overwatering” according to Gregg Thomas — the director of the Environmental Quality division of the Denver Department of Public Health & Environment (DDPHE).

Thomas went on to explain that Denver Water also provides recycled (and safely treated) wastewater to irrigate places like parks as part of those conservation efforts. But, he concluded that “going forward, we will need to be even more diligent as the region adds a million more people and the effects of climate change continue to rear their ugly heads.”

Although two out of 12 goals met does not seem like a significant improvement in the path toward making Denver more sustainable, there have been other successes that should not go unnoticed. One of those is the Green Roof Initiative passed by voters in 2017 to require buildings over 25,000 square feet to incorporate solar energy collection and vegetation of some kind (hence the “green”).

READ: Everything You Need to Know About Voting on the Green Roof Initiative

Once passed, this citizen-led initiative developed into the Green Buildings Ordinance (GBO) which is now regulated by the Community Planning and Development department and the CASR office. In its original language, the Green Roof Initiative was prohibitive for many buildings in Denver, especially historic structures. Without rewriting it as the GBO, it would have been nearly impossible to implement, but unfortunately, much of the original intent was watered down by the rewrite. The 2019 annual report is the most recent progress report and it shows that an estimated 65 construction projects were subject to the GBO between November 2018 and December 2019, adding some green space and on-site renewable energy, but mostly making existing roofs “cool roofs” and decreasing energy consumption.

With green roofs, the city’s air quality improves, the urban heat island effect reduces, stormwater drainage is better managed, buildings are more energy-efficient and added green space provides natural sanctuaries for wildlife as well as people. This ticks the box for several of the sustainability goals and proves that some amount of regulation on an industry can hasten innovations in sustainability.

Goals That Are Kind of “On Track”

In 2017, we explained why Denver’s residential recycling rate was at an abysmal 18%. Although in the few years since then Denver has increased its recycling rate to 25%, it still lags significantly behind other Front Range cities like Boulder (51%). Unfortunately, Denver is also well behind the 2020 goal of residential recycling at 34%, but a few recent developments may help improve rates from here on.

One of those is a set of grants offered to businesses working to divert waste from landfills by recycling, composting or repurposing materials. Another is the Senate Bill 20-055 which set up the first state-wide end-market recycling development center to help businesses process recycled materials. The final is more speculative — a recommendation from a climate action task force that Denver adopts a Pay-As-You-Throw trash system with free recycling and compost. With these incentives to provide more accessible recycling services to residents, it’s likely that recycle rates may increase.

However, just like in the article from 2017, an impediment to landfill diversion in Denver is the lack of regulations on multi-family and commercial buildings, which are currently outside the scope of Denver waste management and therefore do not need to offer recycling and do not need to report their recycling rates for data collection.

Energy consumption is another topic of particular concern recently. Denver’s new CASR office is working on a few efforts to address this lagging section of our sustainability goals including the Energize Denver Task Force and the Net Zero Energy Implementation Plan. In the Net Zero plan, the goal is to have all new buildings at net zero energy (or “highly energy-efficient and fully powered from on or off-site renewable energy”) by 2030. But the fact is that many buildings and residences in Denver are old and outdated and require weatherization and renovation to become more energy efficient.

Something fairly unique about Denver’s approach to energy efficiency is its work on investing in renewable additives to the traditional grid when possible, like solar panels on government buildings and community solar co-ops for residents. When it comes to energy efficiency in new buildings, CASR has also released a roadmap of building code changes to roll out in the next three years that target lowering building emissions and creating a reporting mechanism for commercial buildings to prove they are lowering energy consumption year-over-year.

Another category that has made improvements but still requires even more work to reach the 2020 benchmarks is mobility. The original 2020 sustainability goals stated one-person vehicle commutes should decrease to 60% or less. In 2018, which is the last year that data is available, that number was 68%. Since then, the population in Denver has only grown and the number of miles driven per day in the city has steadily increased, with three out of four residents driving alone to work. On one hand, RTD has added light rail lines like the A-Line to the Airport and the W-Line west toward Golden. But on the other hand, the I-70 expansion project by the Colorado Department of Transportation through Denver has temporarily worsened air quality in the neighborhoods surrounding it and will offer an express lane rather than focus on infrastructure for alternative forms of transportation.

Mobility, even if the 2020 goal had been met, would have ignored that transportation represents 30% of carbon emissions in Denver and “is a leading source of air pollution” according to the Denver government website. So without meeting the air quality category goals, does it matter that residents start carpooling more or taking a bus that runs on gas?

Goals That Still Need A Lot of Work

The problem with claiming success in any particular category is that every category is connected, like a natural ecosystem. Just like mobility should encapsulate emissions from cars, climate doesn’t only include carbon dioxide emissions, it also relates to the ozone quality, energy consumption and regional air and water quality. Denver’s 2020 sustainability goals don’t list ozone in its own category, yet it’s not clear what category it belongs to and it’s only been getting worse.

Thomas, of the DDPHE and a board member of the Regional Air Quality Council (RAQC) mentioned that for ozone, Denver was “downgraded from moderate to serious non-attainment. We needed last summer to be a clean summer to give us an upgrade. Even when we took into account that the air quality was clearly caused by wildfire emissions, we still wouldn’t have met the standard. We are likely to get downgraded again from serious to severe, and the regulations will tighten up.”

Water quality in Denver is another area that needs to improve drastically and has not even come close to meeting the 2020 goal of making “all Denver’s creeks and rivers swimmable and fishable.” Even when you only look at the creeks and rivers and not the lakes, Denver’s water quality is lackluster. Thomas warned that although developers create homes and apartments next to creeks and rivers in the city, it is not advisable to get into Denver’s waterways. “Wash your hands if you’re in the water” especially in the summer is his explicit advice, and that’s only due to the consistent levels of E. Coli. There are other compounds in the creeks and rivers in Denver that are maybe even more nefarious but less obviously bad for you, like selenium and nitrate pollution. In general, the advice from the DDPHE is to not swim in the rivers or creeks, period.

However, the city’s departments in charge of various water sectors have definitely improved water quality from past levels by street sweeping, adding filters to drainage ports to separate pollutants from runoff water and constantly repairing old pipes — apparently, most of Denver’s storm drain and sewage pipes are very close to each other. The Denver Green Infrastructure Implementation Strategy created in 2018 is focused on making improvements to water quality through projects that also improve climate resiliency, air quality, provide urban heat island mitigation and enhance connectivity, all while prioritizing neighborhoods with the highest level of need.

What’s Next?

When the 2020 sustainability goals were initially thought up almost a decade ago, climate change science was still finding its footing, especially in regards to measuring success. Some of the categories, like land use, have not been easy to track and are therefore nearly impossible to rate as done or in progress. This is one of the biggest challenges Denver has faced with knowing whether or not it has reached the long-term climate goals — metrics to track data have changed due to better tools, science, or even the evolution of government agencies in charge of monitoring.

Fortunately, there is hope with the new CASR office and its plans to bridge the gaps between the city agencies that are working toward a central goal of improving Denver’s overall sustainability. Rink confirmed that the city’s reporting metrics will be improved upon, and with that accountability perhaps at the turn of the next decade, we will have more successes to celebrate and more data to prove that we made improvements. And if we take the advice of the Climate Action Recommendations Report written in 2020 by a task force of various expert volunteers, our sustainable future could set an example for the rest of the country to follow.

—

Tune in for our next sustainability article in two weeks giving a glimpse into an ideal sustainable future for Denver.