The exhibition, We The People, has already been planned at the MCA for well over a year. The artist, Nari Ward, has been creating politically-charged sculptures and interactive artwork for nearly three decades. Born in Jamaica, Ward moved to the US when he was a child and currently lives and works in New York City. His work has been displayed prominently across the country and globe, though this is the first time a solo exhibition dedicated to him has come to Denver. We The People originated at the New Museum in New York and traveled to Houston before arriving in Denver.

Though some viewers will say that We The People is timely, in the words of the curator of the show, Gary Carrion-Murayari, people are just catching up to Ward and the topical nature of his work. Many of the pieces in the exhibition were first created in the early ’90s and 2000s but the issues they confront — displacement, neglect, dispossession, poverty, racism and the effects of slavery — continue to persist. It makes Ward’s body of work feel timeless and in the process, it betrays the stagnation of our society.

There is more to Ward’s art than a declaration of problems in the world, however. Each of his pieces is painstakingly made out of mostly found objects and then layered with symbology, emotion, ritual, tradition and intention. The result is not an upcycled piece of artwork that simply utilizes the materials, but rather the transformation of materials for a second life. All of the items that Ward chooses to use are things that had a history related to the people who used it — baby strollers, clothing, shoelaces, keys. In many ways, Ward’s sculptures are a path toward redemption, not only for the items themselves but also for the artist and for the viewers who engage with his work.

His mostly monumental artworks take on an almost spiritual presence in the room they reside in and each one is deserving of inspection from many angles. His art exposes wounds and then begins the process of healing them. It is up to the viewer, or sometimes the participant, to continue the process of healing after experiencing the work. In this way, Ward’s art is like a tonic — bitter to taste but good for you to drink.

In Iron Heavens (found on the second floor), this interaction between destruction and redemption is portrayed in a variety of ways. The baseball bats signify the American identity on one hand, and on the other, they signify violence against Black and brown people. But the bats are burned, badly, and stacked up like kindling for a massive bonfire. That imagery evokes a struggle with America and its identity while also signifying relief for those who have violence inflicted upon them. Ward doesn’t stop there though. That is the wound. In order to begin the healing process, he made “pendants” or “amulets” with cotton and sugar that he affixed to the baseball bats. The cotton and sugar are, of course, heavy with their own history. But the act of making the amulets — dipping cotton in soda, ironing the edges of them and drying them — and of placing them on the charred bats are acts of healing, according to Ward.

That is only one way to interpret Iron Heavens, and like the rest of Ward’s work, any way you look at it is thought-provoking. The presence of oven pans in the piece, for instance, speaks to an element of femininity or class politics which can change the vision of the baseball bats below. To Ward, those oven pans are also reminiscent of starry night skies. But the best example of this interchangeable nature of Ward’s art is with his most well-known piece, Amazing Grace.

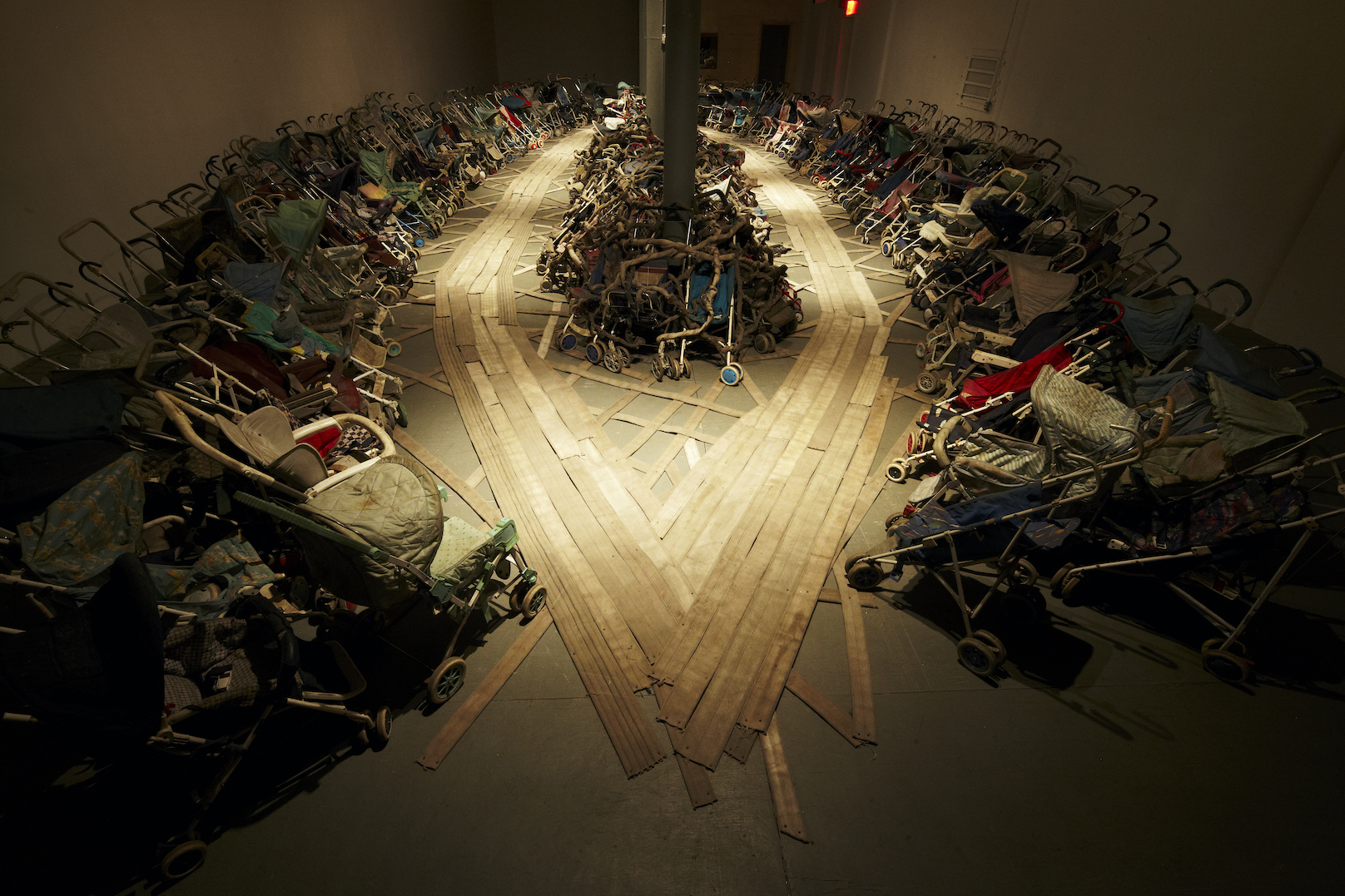

Composed of hundreds of old baby strollers and broken fire hoses, Amazing Grace occupies an entire room. Rows of strollers face inward toward a group of tangled strollers bound by fire hoses in the middle, surrounded by fire hoses placed on the ground like planks of wood in a boat. Some people see the shape of a slave ship. Some see the shape of a womb. Some only see the strollers and don’t think about the shape of it at all. Accompanying the visual scene is an audio recording of Mahalia Jackson singing “Amazing Grace.”

This piece first debuted in 1993, also at the New Museum in NYC, where Ward was an artist-in-residence at a program that was set up to acknowledge and give a platform to artists of color. Since then, Amazing Grace has traveled across the world, and in the process, has carried different connotations along with it depending on the societal issues in each new place and point in time. Where the strollers signified the homeless population to Ward at the time he made the piece — homeless people used strollers to carry their belongings in NYC — to others, they incited ideas about children, mothers, epidemics, inequity.

Symbology is another driving force in Ward’s art. Some of it is open to interpretation — like the fire hoses and baby strollers — but some of the symbols have specific historical references that are important to realize. One of those is the Kongo cosmogram pattern. Composed of a diamond intersected by two lines, the Kongo cosmogram is a prayer symbol that was used on the Underground Railroad to denote Churches that were safe stops for slaves fleeing north. Not only was the symbol a sign of safety, but it was also a way for people hiding beneath floorboards to breathe.

In Breathing Circles, the cosmograms are surrounded by copper nails and wire, emanating out from the point in the middle. Ward uses copper in this work and others to once again denote healing, as copper has medicinal properties and has been used for thousands of years in many cultures across the globe to heal a variety of ailments. Standing in front of each one of these circles and breathing deeply is a meditative practice that will bring you closer to the work, to the reason behind the cosmogram on the floor of churches. And, true to form, Breathing Circles has even more resonance now, in the age of wearing masks and dealing with a virus that disproportionately affects Black communities and other people of color in the US.

“I think everyone has gone through a reckoning — personally, professionally, creatively — over the last several weeks, and if this exhibition can help in that process, then that feels like a great honor to provide it,” said Nora Burnett Abrams, Mark G. Falcone director at the MCA. “Museums should force the dialogue, catalyze the conversations around the most pressing issues of our day,” but ultimately, she insisted that the museum served as a platform for Ward and his already prescient work.

The title piece of the exhibition, We The People, is one of the most hopeful. In one stride it both criticizes the US constitution and redefines it. Using hundreds of unique shoelaces that are drilled directly into the wall of the gallery, the piece evokes the font and words of the foundational rights of our country. But we all know that those words weren’t meant for literally everyone when they were written. By using the wide variety of shoelaces, Ward places emphasis not on the fallacy of the phrase but on the individuality of the laces that make up the structure of the words. We The People allows each viewer to relate to a single shoelace, realizing that a society or country or community is only whole when each piece is represented equally.

There are many other pieces in We The People that deserve exploration — like the video Father and Sons (2010) which depicts two Black teenage boys with their retired police officer father or the copper-covered bricks on the floor that depict patterns used in quilts. But ultimately, all of the pieces in this exhibition are incredibly powerful works of art that deserve further exploration. They exist outside of the normal constraints of time, able to shapeshift and take on new meanings as they mature. Much like the found objects they are made with, Ward’s artwork has multiple lives — all of which yield generous doses of exaltation to the viewer.

—

Nari Ward’s We The People is on view July 1 to September 20, 2020 at the Museum of Contemporary (MCA) Denver, 1485 Delgany Street.

Tickets (and masks) are required for entry, here.