Making ordinary materials extraordinary is not a new technique for practitioners of creative endeavors. In many ways, that’s what all art is — repurposing materials into something unusual, novel or unique. But with the newest exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) Denver, visiting artist Tara Donovan converts ordinary objects so completely that viewers must remind themselves of the basic origins of her work, or risk losing themselves in the splendor and visual stimulation. Using things like rubber bands, broken mirrors, tar paper, dressing pins and Slinkies (okay, maybe Slinkies are the least “ordinary”), Donovan constantly studies patterns, light and the movement. Partly because of this adventurous and curious spirit that Donovan approaches her artistic practice with and partly because the work displayed at the MCA takes on a natural or organic appeal, the show is titled Fieldwork.

Fieldwork, as stated before, is an exploration. But it’s not just an exploration that Donovan undertakes as the artist — instead, her work presents to viewers the chance to explore a medium with her, and especially so in this exhibit. For the first time in her career, Donovan’s 2D and 3D pieces are displayed together, illuminating the artist’s utter determination in exploring different materials and forms. Plus, the MCA converted the entire museum (all three floors with gallery spaces) to Fieldwork. “It’s such a big story to share that it felt like we needed to give it the whole museum,” curator Nora Burnett Abrams explained. “It’s important to show that she’s exploring the same ideas on paper as well as in the round. In working in one manner it speaks and is in dialogue with the other. It’s a testament to the rigor and commitment and dedication she has to her own practice. She wants to know what that material can do in every possible way.”

The art displayed in Fieldwork spans throughout Donovan’s career — including a never-before-shown sculpture from Donovan’s studio in grad school, from 1991 — although it’s not presented in chronological order. Instead, the approach to showcasing her work revolved around the materials themselves — a testament to Donovan’s continuous study-and-discovery method.

“I rely a lot on chance encounters,” the artist said in an interview with Abrams. “There’s this real sense of play in every project that I do. Once I’ve discovered what a material can reveal, then I go into a factory production mode.”

One of the best examples of this way of thought and action on Donovan’s part is in the first gallery, where thousands of straws are stacked against the wall. This installation, called Haze, changes the rigid plastic of the straws into a soft, out-of-focus backdrop just by aggregating them in so many numbers. Donovan has done almost nothing to these straws — she hasn’t colored them, glued them together, changed the way they “rest” by bending or breaking them — and yet the first reaction to the piece wouldn’t betray that they are straws. It might even slide by unnoticed to a viewer, without a closer look or an informational packet. It’s also impossible to photograph, so we recommend seeing it for yourself.

In the next room, all the textures and colors oppose the first room with the straws. In the middle of the floor is a mass of ripped and stacked tar paper — a material typically used for roofing — that takes on the appearance of a vast expanse of shale (a form of flat, flaky rock) or a topographic map. The dark color and solidity immediately take the viewer away from the dreamlike fluffiness of Haze and into a world where geologic forces dominate. On the walls in this room, viewers experience Donovan’s 2D pieces for the first time. These are prints of shattered glass and they reciprocate the jagged edges of the tar paper as well as embodying the expression of another geologic force — pressure. When Donovan created these prints, she inked a piece of tempered glass and smashed it, then used a press to imprint the resulting pattern onto paper.

Two ballpoint drawings in the following room are paired with the most Instagrammable piece in the show, Untitled to demonstrate Donovan’s uncanny ability to harness natural movement into relatable patterns. The drawings were created in 2002 and followed a freehanded approach by Donovan. Another piece of hers, the golden window of cylinders (which you see when you first walk in) was created just this year — and yet, despite the difference in materials, process and time, the general shape and design are shared.

The final room on the main floor of the museum has been turned into a cavern of sculptures. The monoliths — reaching over 11 feet high in some instances — resemble stalagmites or termite mounds or maybe something more whimsical. But, just like with her other monumental pieces, these are made by stacking thousands of individual items, in this case, polystyrene index cards. Although the room is nearly full of these incomprehensibly time-consuming stacks of cards, standing among them results in a calm feeling, like an embrace. Her work, aside from displaying her commitment to exploring material, has a special quality to it that begets a sense of growth — as if the viewer has walked into a teeming ecosystem.

Move to the upper level after experiencing the cavern in order to see another approach, by Donovan, at changing the use and appearance of index cards. Fourteen separate pieces await, framed and hanging on the walls, showing various patterns. The patterns bring to mind a host of organic things like waves, crowds of people, tree bark, sound waves and heartbeats but are created entirely out of vertically stacked cards. One of the pieces — in the hallway — was created this year and the MCA show is its debut appearance.

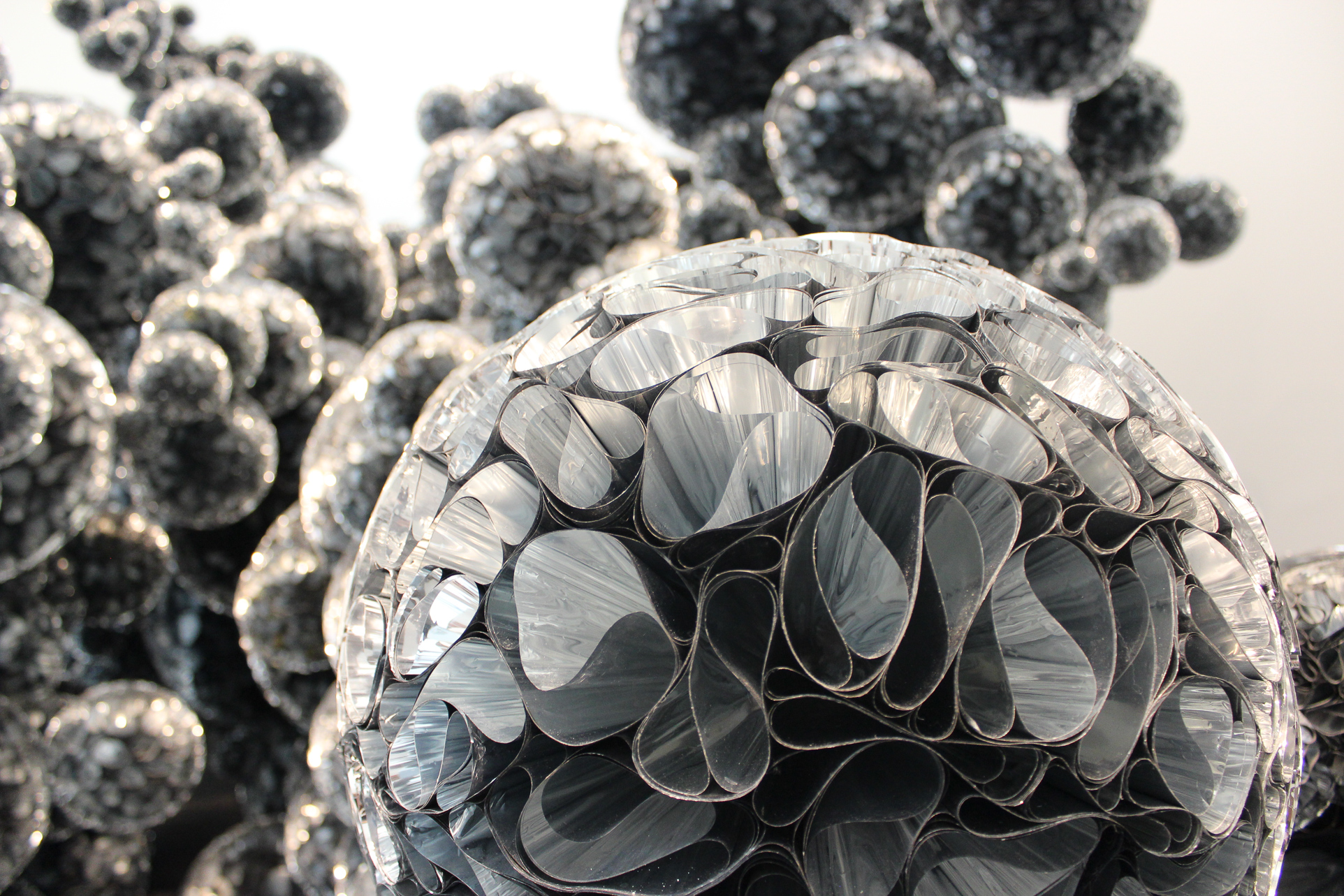

The straight lines and blanched tones of those 14 pieces are again (like the first and second galleries) in juxtaposition with the following sculpture, Untitled (Mylar), which is made of curves and spheres and a shiny, dark material. The sculpture is awe-inspiring and dazzles the viewers by reflecting the lights in the gallery. But as much as it pulls you in, it also has the capacity to intimidate — sometimes looking alien, or like a larger-than-life representation of an extremely small molecule, virus, bacteria or mold that should never be so big. As the title explains, the entire installation is made of Mylar — a polyester film often used as electrical insulation.

Though the rest of the upper floor perfectly suits the themes of the exhibition, it is the lowest level that knocks it home for viewers. The best way to experience the splendor is by taking the elevator — so that when the doors open you can see both the sculpture and the flattened approach on the wall in the back at the same time. This view — and the fact that both are made entirely of Slinkies — helps to remind the viewer that Donovan is fearless in her approach to materials. She is able to understand a material as something of form rather than utility, aesthetics rather than functionality. And when she experiments, the results can be unexpected and unexpectedly natural despite the completely unnatural (and pretty unsustainable, to be honest) source of the materials.

Donovan can make clouds from plastic straws or a valley of shale out of tar paper or a wall of tiny bubbles out of mylar and her adventurous trials with these materials are always informed by how the material moves or takes shape on its own. In an esoteric way, her work is feminine because she doesn’t aggressively assert her will onto these materials. But taking gender out of the equation, her work is meditative, empathetic and full of vibrancy. For Donovan herself, the study is about making things work as something they aren’t. For the viewer, the study could be as simple as reveling in the beauty or it could be remembering places in nature that are brought to life by the finished products of her process. Whatever the case, Donovan’s takeover of the MCA will make you think twice about that junk drawer or closet in the house with all the ordinary items that go unnoticed. And maybe that’s the biggest study of Fieldwork — finding the extraordinary when you least expect it.

Fieldwork will be on view at MCA Denver until January 27, 2019. On November 8, 2018, viewers can hear Donovan’s point of view at an artist talk — details and tickets for that are here.