Since its establishment, Denver, Colorado has been a unique hub for North America. Its urban development and population growth has waxed and waned alongside economic trends — turning the city’s skyline into a timeline that marks each era through fluctuating architectural styles and reflects a continuously changing world, nestled against the unwavering shadow of the Rockies.

This perpetual boomtown shouldn’t exist, much less thrive. It’s in the middle of a vast country, blocked by a major mountain range to the west, and hundreds of miles of prairie land to the east with no easy water access. Despite its location, harsh western terrain and dry climate, Denver has become the 21st largest city in the U.S. and continues to grow.

When the city was first founded, there was little hope that it would last. Thomas J. Noel or “Dr. Colorado,” a Professor of History and Director of Public History, Preservation & Colorado Studies at the University of Colorado Denver, explained, “The difference was the people involved – the human beings who worked to keep the town alive. There were a lot of ambitious people who laid the groundwork for the Denver of today.”

When we stroll past the brick buildings on Larimer Square or notice the Cash Register Building glistening against the mountain backdrop, we see more than an architect’s pet project, more than an ego jutting into the sky. We are witness to the story of people that came before us. The varied architecture that makes up Denver combines previous residents’ need for function and aesthetic desires with current residents’ plans for the future and acts a bridge connecting us to a time, place and people that we may never have otherwise experienced.

Each wave of newcomers feels as if they bring the next greatest hit – be it gold, silver or green. In reality, we are but one wave in a set that has long been washing over this city, depositing pockets of history in the form of steel, stone and glass throughout the ever-developing western town. Even though our own legacies may be just a page in a long storied history, it’s important to care about the effect of that page on the whole narrative. It’s important to acknowledge others’ legacies and to appreciate what and who came before us, while we are on our path to making our own.

Colfax Avenue – 1868

Colfax Avenue first appeared on Denver maps in 1868 as the main vein connecting the town to the Rockies. Born out of necessity to facilitate trade and aid gold miners on their trips to the mountains, Colfax remains to this day the longest commercial street in America. Originally, the strip was named “Golden Road,” then “Grand Avenue” and finally Colfax Avenue in honor of Schuyler Colfax, the Speaker of the House of Representatives.

Colfax boasts a myriad of neon signs advertising every kind of business including bars, restaurants, motels, cars and lumber. If you need something, you can find it on Colfax. Pete’s Satire Lounge is also marked by one such sign. Pete Contos has owned Pete’s Satire Lounge for over 50 years. He’s the proprietor of many other Denver restaurants including Satire’s neighbor, Pete’s Kitchen. The building that houses Pete’s Kitchen was erected in 1942. However, the birth date and architect of Satire’s building remain unknown. Much like Colfax’s teal and pink neon signage, both of these institutions are Colfax staples.

My Brother’s Bar – 1873

Architect Unknown

My Brother’s Bar is the oldest continuously operating bar in Denver. Just setting foot in My Brother’s Bar transports one to a different era – an era where whiskey was less likely to kill you than water, where folks gathered to share stories and ideas in the middle of the work day and where your word could postpone payment of a tab, indefinitely (see Neal Cassady’s I.O.U. letter hanging up in this historical haunt).

As Denver’s oldest bar, My Brother’s Bar has gone through quite a few name and ownership changes over the years. It started as Highland House in 1873, then became Whitie’s Restaurant for some time before changing to the Platte Bar, then Paul’s Place, and finally My Brother’s Bar — so named because each brother was attempting to avoid bill collectors and delivery men by sloughing off ownership to the other brother.

My Brother’s Bar is dimly lit, bartenders wear floor-length aprons and button-down shirts and you’ll most likely find classical music playing in the background. The building itself is muted and unassuming; it doesn’t even have a sign out front. But its true architectural beauty reveals itself inside. The natural material used is showcased by the ornate ceiling tiles, the polished-yet-weathered wrap-around wooden bar and the intricate molding throughout the entire restaurant.

“Colorado architecture is not defined by an aesthetic style or movement. Like the history of the state, it developed out of a sense of independence, hard work and talent. Buildings are designed to address issues of function, sustainability and environment with a watchful eye to budget and schedule. The dynamic skyline of Denver today is a composition of shapes, colors and materials that illustrate the vitality of the city.”

– Larry Friedberg, Colorado State Architect

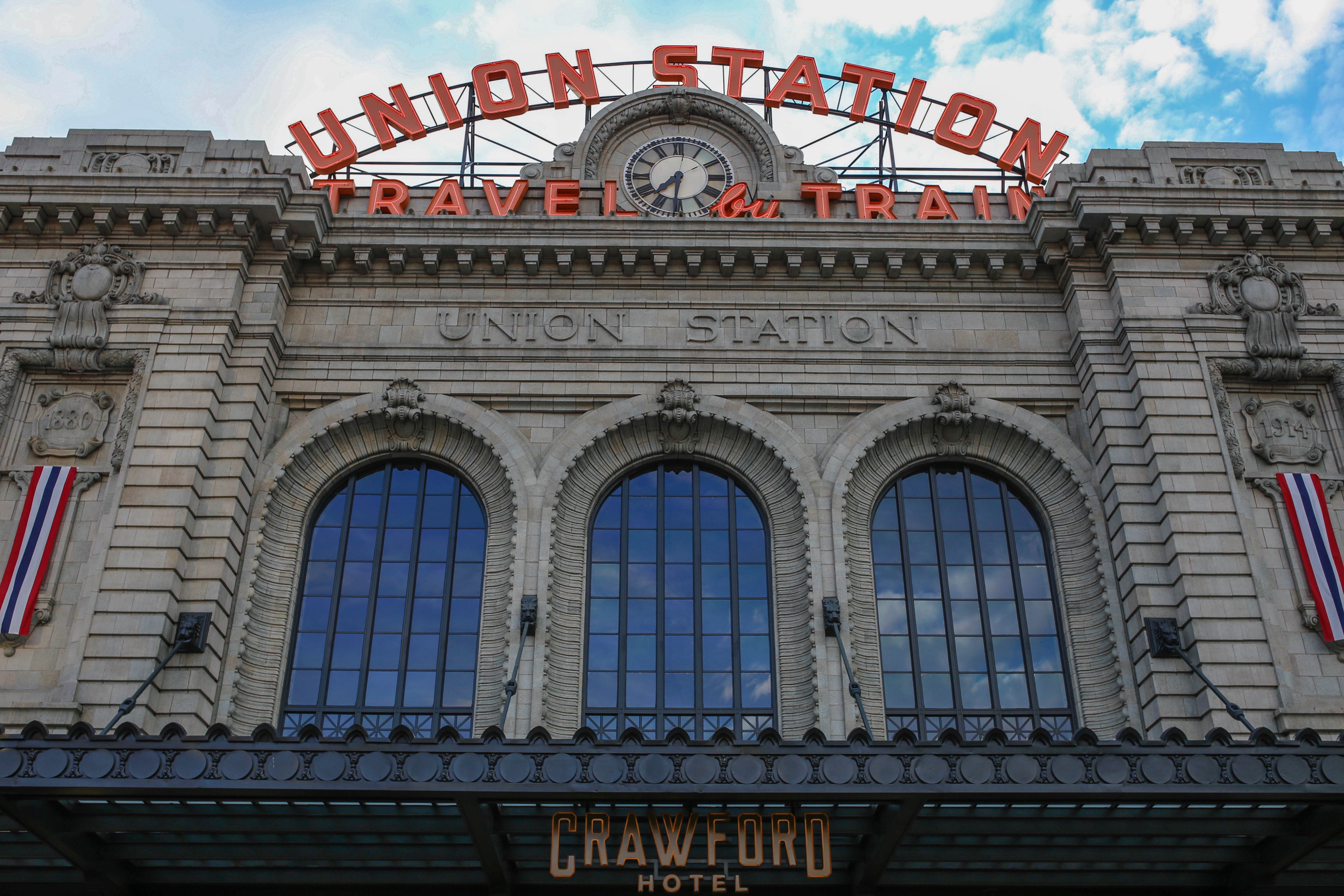

Union Station – 1881

Architect: D.H. Burnham & Co.

Denver’s Union Station is a building marked by each decade it has endured. This Beaux Arts-style framework has been through fires, floods, economic turmoil that threatened rail travel itself, and two major renovations in 1914 and 2010-2014. From 1865-1958, Denver saw the glory days of train travel. Tourists, new residents and entrepreneurs looking to strike it rich with whatever the hot commodity was at the time, flocked to the city and entered through Union Station.

Now, the building houses much more than rail lines and it continues to commemorates its roots. Union Station had to evolve to include new transportation projects, retailers and interior designs in hopes of staying relevant to the expanding population and technological advancements. After the latest remodel in 2014, Union Station now sits as a tribute to how we got here and a launch pad for the next generation of creators.

Molly Brown House – 1889

Architect: Willian Lang

One of the most well-known Victorian Era symbols in Denver, The Molly Brown house was almost bulldozed during Denver’s 1960 Urban Renewal Project. Through fundraising, campaigning and the formation of Historic Denver, Inc. The unsinkable lady‘s house still stands to this day, restored to better represent the original architecture and interior design. The Molly Brown House is a combination of popular Victorian Era styles of architecture — Classical Queen Anne, Richardsonian Romanesque and redefined neoclassical.

Much like Molly Brown herself, Victorian-Era architecture was eccentric, noticeable and elaborate. Brown was known for her dramatic hats that caused her to stand out among the more muted attire of her time. The Molly Brown House is a tangible reminder of its namesake’s memory, as its curved arches, ornate molding and asymmetrical facade stand in juxtaposition to the plain, symmetrical apartment buildings on Pennsylvania Street.

The Capitol Building – 1894

Architect: Elijah E. Myers

Intentionally recollective of our nation’s capitol building, Colorado’s capitol building stands as an architectural representation of what our state has to offer. The dome is adorned with copper panels and gilded with gold from a Colorado mine – celebrating the Gold Rush that first put our city on the map. In 2010, the capitol building underwent a 17-million-dollar restoration. The new guild uses 65 ounces of gold that is spread 1/8000 of a millimeter.

The complete supply of Colorado Rose Onyx adorns the interior of our city’s Capitol building. Along the front steps, certain mile markers are installed, stating the most up-to-date measurement of exactly one mile above sea level. It’s a building all about Colorado.

Friedberg provides deeper historically insight:

“When Colorado became the 38th state in the union in 1876 it was without a state capital building. A nation-wide design competition was held in 1885 and Elijah Myers of Detroit, Michigan won with his entry named “Corinthian” and received the first prize of $1,500. The overall plan of the building was a Greek Cross and housed virtually the entire state government in 1901 when the building was completed. However, the copper-clad dome exterior finish was subject to much controversy and was painted various colors until the state legislature decided to gild it in 1908. Although the building no longer houses all of state government, it serves as the seat of state government and an iconic symbol of Colorado. Through continuous restorations and preservation projects, the Colorado state capitol building perseveres as a symbol of pride for the citizens of Colorado.”

Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception – 1911

Architects: Leon Coquard, Aaron Gove, Thomas Walsh

Churches are the greatest measures of architectural progress and prowess. Most are backed by large sums of funding and their constructions have spanned centuries, and will continue to do so well into the future. The Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception is no exception. This gorgeous, cruciform house of worship was designed in the French Gothic style, as many of its European brethren were. Gothic-style architecture incorporates ornate, elaborate elements such as intricate gargoyles, decorated flying buttresses, high pointed arches and vaulted ceilings.

Interestingly enough, all of these elements are vital to the support of the structure itself. It’s not just art for art’s sake! It’s also not just an ostentatious display of wealth. While the cathedral’s facade and interior is fanciful and elaborate, each seemingly decorative element actually aids in supporting the heavy stone used to build the church. Function and form combine in the Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception to give a deeper meaning to this quickly expanding city.

Poet’s Row – 1930-1950

Architects: Charles Strong, Robert Strong, Andrew Willison, and Unknown Architect

Poet’s Row is home to charming yet understated art deco apartments that bare the names of literary greats like Mark Twain, Emily Dickinson and Robert Frost – to name a few. Poet’s Row is a collection of 11 unique but cohesive apartment buildings that, when they were first built, offered affordable and stylish housing to Denver’s Great Depression-Era citizens.

The buildings withstood the test of time, their popularity only increasing with the influx of new blood to the Mile High City. These structures mix mediums; glass, iron and brick can be seen throughout the row. Curved lines, colorful and decorative tiles and geometric shapes mark these buildings as art deco and make them approachable while remaining trendy.

Sculptured House/”Sleeper House” – 1963

Architect: Charles Deaton

This house, just outside of Denver on Genessee Mountain, is easy to overlook when driving on I-70 towards a weekend of skiing. The Sculptured House, or “Sleeper” House, was used in the 1973 Woody Allen film Sleeper and has stood devoid of residents ever since. The house changed hands a few times, was remodeled in 1999 and underwent foreclosure in 2010.

The heliocentric design looks contradictory against the angular rocks and expansive horizon, but somehow, “The Sculptured House” fits cohesively into its environment. The house is futuristic but not aggressive. It sits a top that hill, slightly forgotten but not alone, representing the fleetingness of pop culture and style trends of the ’60s.

Its twinkling, rectangular windows are framed by curved, white concrete that creates a smile, good-naturedly teasing and reminding the passersby about the impermanence of the physical man and the eternalness of his ideals.

Boettcher Memorial Tropical Conservatory – 1966

Architects: Victor Hornbein & Edward White Jr.

This past year, the Boettcher Conservatory turned 50 years old, and it is still considered an architectural marvel. It’s considered one of the greatest greenhouses in the world and was registered just seven years after its erection as an official historical landmark. Since its opening, the conservatory has been an important and essential building to our city’s footprint.

Most green houses are exactly that — houses. This building is both sculpture and home. It’s geometric, modern and complimentary of its surroundings — unusual for a post-war building, which typically value function over beauty. The Boettcher family, who funded this project, owned Ideal Cement Company, and encouraged the architects to utilize cement in the creation of the green house. This proved challenging because concrete is heavy and doesn’t allow any light to pass through.

Ultimately, the builders decided to go with cast-in-place concrete, making it the only conservatory in the country to do so. The 116 concrete caissons extend 25 feet into the earth. The geometric skylights are made of plexiglass and shaped so as to prevent humidity from condensing, stopping any potential showers on visitors below.

This structure is important because its design allows for tropical plants to flourish and thrive in a place of the world where they normally wouldn’t. Denverites can experience a warm getaway complete with colorful flowers and lush, greenery in the dead of winter.

Wells Fargo Center/”Cash Register Building” – 1983

Architect: Phillip Johnson

Nothing quite marks the Denver skyline like the “Cash Register Building.” Its curved roof breaks up the usually pointed skyline. This building falls under the “Post Modern” category and is shaped like the thing, person or place it’s supposed to represent, hence the cash register shape. It’s a pretty self-explanatory building, but it’s so vital to our city’s identity.

Between 1966 and 1984, Colorado experienced an economic boom, adding 800,000 new jobs and 1.2 million people. There was more money in Colorado than there had ever been and a need for banking centers, office and retail space. Thus, the Wells Fargo Center was born. Just two years after this oil and tech boom, Colorado was at a historically high unemployment rate. The Cash Register Building cast its shadow on the now sparsely-trafficked 16th Street Mall, waiting to become useful once again. More than any other building in Denver, The Wells Fargo center shows the successes of the city’s past, its resolution through hardships and the possibilities of our collective future.

Denver International Airport and The Westin – 1995/2015

Architect of Airport: Fentress Architects

Architect of The Westin: Gensler

Both The Denver International Airport and The Westin Hotel are built to compliment their backdrop. The white peaks of the Jeppesen Terminal serve as a welcome sign to travelers arriving or departing from this city tucked against the mountains. The sleek, unbroken lines of The Westin are the perfect tribute to the high plains in the East. Each structure represents how architecture has taken on a different form in modern times. Instead of positioning itself against nature, to shelter man against the outside world, it seemingly works alongside its natural surroundings to meld the two worlds through minimalism and mimicry.

Gensler describes the thought behind the design of The Westin Hotel:

“Building upon imagery of flight and aviation, the sleek form resembles a bird with its wings extended as it hovers above the public plaza, framing and accenting the acclaimed tents of the Jeppesen Terminal.” These are structures that welcome, invite and describe the city they are about to present.

Denver Art Museum: Frederic C. Hamilton Building – 2006

Architect: Daniel Libeskind

Nothing is more simultaneously natural and unnatural than Denver Art Museum’s Frederic C. Hamilton Building. It is angular, asymmetrical and depending on the position of the sun, blinding. For a building meant to house art, this building is a work of art in and of itself. It makes a statement and, with 9,000 titanium panels covering its exterior, reflects nature in the most literal way. Libeskind said, “I was inspired by the light and the geology of the Rockies, but most of all by the wide-open faces of the people of Denver.”

The building is a landmark that begs attention and seamlessly fits into Denver’s Golden Triangle. Its Postmodern form represents that architectural time period and allows the building to be both stunning and assertive, amongs other architectural and cultural wonders.

25th & Larimer – 2013

Architect: Davis Urban Architecture

25th & Larimer has a design uniquely its own in Denver. This retail and office space is made up of 29 shipping containers and houses nine tenants that “share the same ethos” as the designers and architects themselves.

This project calls forth a new wave of architecture that combines aspirations of beauty with sustainability and innovation. 25th & Larimer is an aesthetically pleasing billboard about the benefits of recycling and collaboration. The space and structure are a nod to any and all efforts to rescue our natural and social environment from a dismal future consisting of concrete jungles and communal indifference. The recycled shipping containers perfectly meld past, present and future.

Emerson Street Rowhouses – 2015

Architect: Meridian 105 Architecture

Located in Capitol Hill, these modern row homes don’t quite fit into the historic neighborhood they were placed in. However, they show a change in modern human needs from their exterior and interior design.

With land space quickly filling up in Denver, Emerson Street Rowhouses instead go skyward with their living spaces. Including the roof top level, these condos reach four stories tall and seem to look at everyday life from the human perspective. The kitchen is in the middle-most portion of the elongated floor plan and the outdoor space is ample. This is a building that recognizes its environment and its inhabitants by emphasizing what each really wants and needs – to feed the body and soul.

Denver boasts unique and varied architecture that spans centuries. Here’s to another hundred years of innovation that melds form and function, and keeps our city on the map.