On October 6, Colorado Humanities — a nonprofit based in Greenwood Village — hosted the virtual panel, Changing the Legacy of Race and Ethnicity: Conversations for One America, to discuss policy reform and accountability in the criminal justice system with input from policy, legal experts and the Aurora Police Department.

“In America’s history, policing has a very unique foundation,” said former Colorado State Representative and Senator Penfield W. Tate III during the chat. “Now, we’re looking at an environment where we’ve seen a number of issues with policing around the country.”

READ: This Weekend, Young Activists Took To the Capitol To Protest Ongoing Police Brutality

Tate added that the widespread shift towards policing accountability, sparked by the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and Elijah McClain by the Aurora Police Department within the past couple of years, demands more, long overdue, conversations about policy reform and understanding the racial biases embedded in the criminal justice system.

“Elijah was walking in his own neighborhood,” explained Tate. “It’s unfortunate that people didn’t know he was a kid, but it’s distressing that someone can make an anonymous call and say they see something suspicious and then you have this potential encounter.”

Aurora Chief of Police Vanessa Wilson argued during the panel that despite the need for more reform and transparency, she believes change begins by educating and training officers to police communities appropriately and safely, without demonizing the police institution altogether.

“You have to be able to open yourself up to realizing and accepting what it is that you’re fearful of or what biases you may have. It’s a huge issue that we categorize people and neighborhoods as communities,” added Chief Wilson during the panel. She emphasized the urgency to repair broken trust between police and communities of color: “Race is an issue we all need to talk about and stop shying away from that conversation.”

Options for reform were the focus of the panel, particularly how police culture has shifted in the country and what can be done to protect BIPOC communities from those shifts while taking into consideration how other states have taken steps to prevent escalation and excessive force.

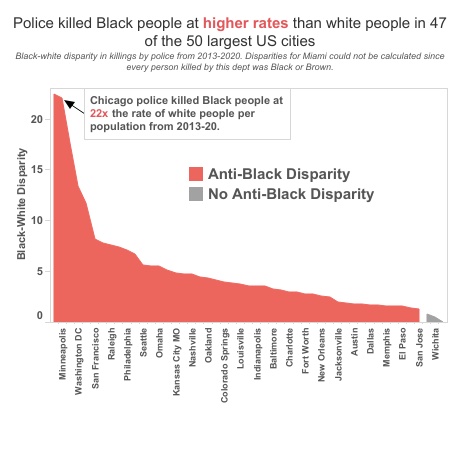

According to a report by the Prison Policy Initiative, police in the United States kill civilians at higher rates compared to other affluent countries, with communities of color bearing the weight of those deaths.

Independent monitoring, for example, is a form of civilian oversight to review any sort of allegations or misconduct reported on behalf of a negligent officer. The City of Denver’s Office of the Independent Monitor is a civilian oversight agency that reviews and investigates claims of officer-involved shootings and other negligent behavior. According to its annual report from last year, the Denver Police Department (DPD) had 11 officer-involved shootings — seven of those victims were men of color.

“Most cities in the United States have developed some form of civilian oversight, some have independent monitors. Some smaller communities have community boards that get involved in these kinds of cases,” explained former independent monitor of DPD Nicholas Mitchell. “I view myself as a partner with the city and executives in the agency of pushing towards the same goal, which is improved policing and greater community trust.”

Failure of public safety and policing have become a polarized topic in policymaking this past legislative session. Governor Jared Polis signed Senate Bill 217 into law in June of 2020, which will require all on-duty police officers to wear and activate a body camera when responding to a call.

Some call for abolishment, some argue that policing is under attack, while others believe reform is the necessary sweet spot to fix the issue. Others call for defunding the police or allocating funds to other resources like education and healthcare. But what do the communities that have been impacted the most by police negligence and brutality want to see? If they had a say in it, some more clarity and direction could be given. But they didn’t have a say in it, and they rarely have a say in policy change. Just how effective these conversations are towards shifting concrete change, then, is questionable.

“It’s not a new phenomenon. What’s distinct this time is that, across the country, there is a multicultural interest for change,” commented Cooper. “It is shared across the board, and that has created a demand for legislatures and policymakers to have to respond because this is what we elected them to do: represent the interests of the people.”

Despite the discussion being centered on policing communities of color, perspectives from these communities weren’t represented in the panel. However, a live chat forum enabled public comment.

“Policing was formed to protect white people, especially white women. That ‘Old Guard’ isn’t going to want change,” added Katie Bird in the public chat.

“As long as officers do not face taking responsibility for their actions there will not be change. And accountability has to be daily, not just for the high-profile cases,” added another viewer, K Tate.

Colorado Humanities is a nonprofit organization that was formed in 1974 to promote humanities education and engaging conversations about culture and social issues.