We are in a state of emergency in all of the forms that that phrase encompasses. As journalists, our job is to look at all of these facts, all of these moments, and catalog them, bring them to the reader, regardless of whether or not the reader can take more bad news. Although that will never stop being our job, it doesn’t always sit right with us. Beyond the critical information that shifts every day, there is an underlying world of thought and feelings that statistics cannot touch. Our people, the Denver community, are a multi-faceted, resilient bunch, but that doesn’t take away from the singularity that social distancing, infection rates and public policy changes can have.

In times like these, the responsibility on our shoulders also becomes an opportunity to help by letting others tell their stories, stories that readers can relate to. Grief is a process, an often lonely experience, but there is something to be said about being sad, being broken, and owning it — allowing others to say “I’m here with you.”

We have reached out to community builders, frontline workers, creatives and other media outlets to provide a glimpse into their worlds, give them a voice that will resonate with yours and (hopefully) provide comfort in the discomfort, because as lonely as this can be, Denver is a city of community and part of the battle is remembering we have that when everything else feels less concrete.

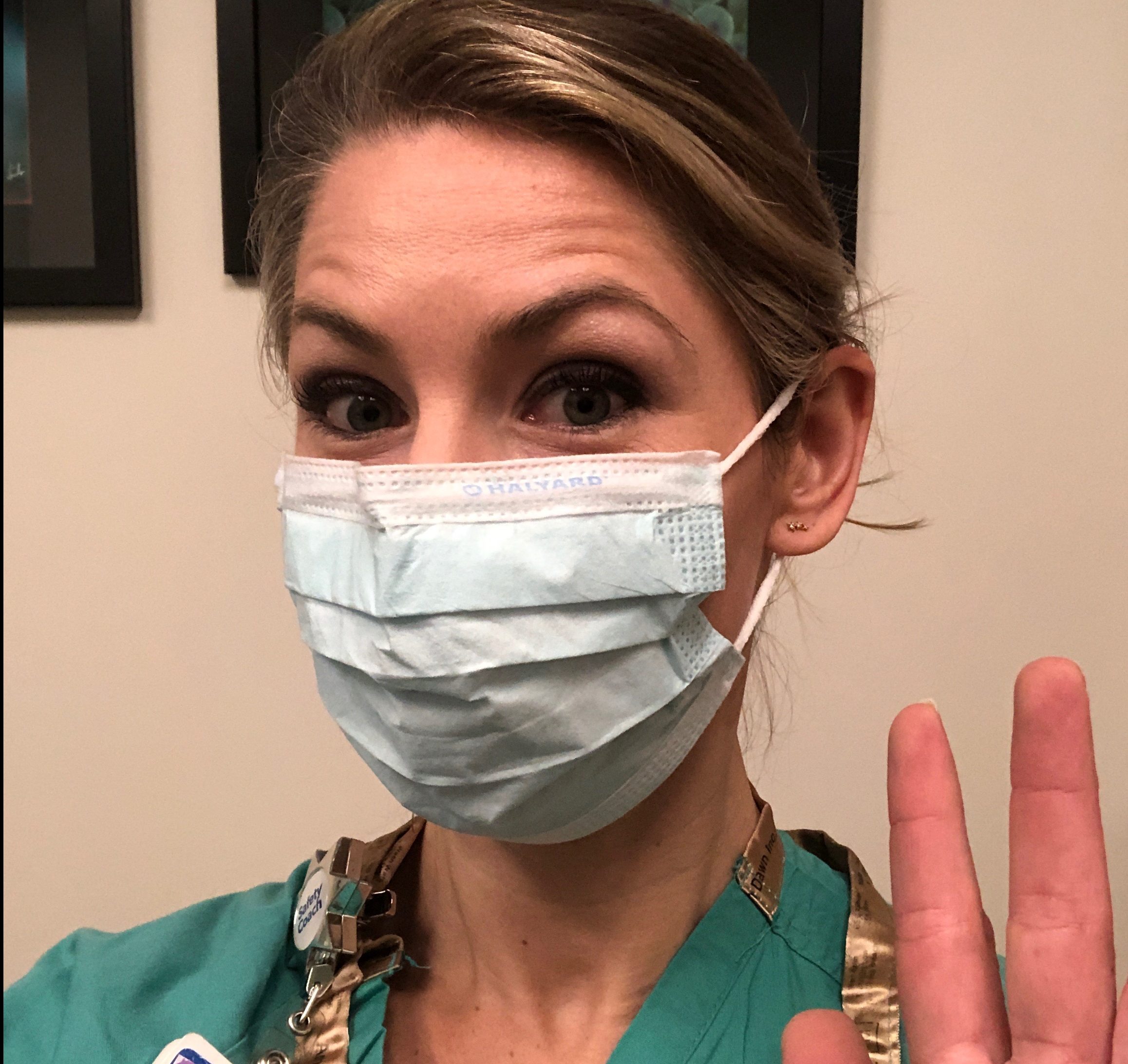

Lori Fensterman

Patient Relations Advocate for SCL Health

I am a registered nurse no longer working at the bedside but as a Patient Relations Advocate. I like to describe my work as the intersection between patient experience, healthcare quality, safety and risk management. As the reality of how COVID-19 would impact patient care started coming into view, it became apparent that patients and their family’s needs were almost as dynamic as the care and treatment recommendations for treating patients with COVID-19. As the visitor policy became more restrictive and the workload of physicians and nurses exponentially increased, clinical updates for our patient’s families were adversely impacted. Our Chief of Medical Staff/Chief Hospitalist requested that I transition into a new role as a Nurse Liaison. This role would serve to bridge communication gaps between our care team and the families of our most critically ill patients with COVID-19.

I knew this role would be challenging but I never expected it to provide so many opportunities to witness the beauty, overwhelming distress and ultimately the human spirit’s remarkable ability to triumph during dark times of uncertainty and loss. To figuratively sit with families in potentially some of the darkest moments of their lives has been an honor. Witnessing the joy and excitement of loved ones returning to their families after being hospitalized for well over a month, and having been so close to death has touched my heart in ways I never expected. I have been provided the opportunity of being welcomed into the families of people I have never met face-to-face. I have witnessed physicians and nurses putting every ounce of their being into saving the lives of their patients, knowing that for the majority, treatment may ultimately be futile. Holding an iPad up to a patient who lies on a hospital bed hooked up to an army of machines keeping them alive for their children to say goodbye was devastating, yet undoubtedly a special privilege.

I have only started to process all the varied experiences this pandemic has provided, and the many emotions that go along with them. It has encompassed some of the most heartbreaking and heartwarming experiences I’ve had during my 20 years of working in healthcare, which has made me grow in ways I previously could not have imagined and left an imprint I hope will last forever.

Kali Fajardo-Anstine

Local Author, Sabrina & Corina

On March 12, 2020, I was set to sign a lease on my dream apartment near City Park in downtown Denver. The home was built in the early 1900s by a former mayor of the Queen City of the Plains — Perkins or Arnold but certainly not Speer. It was an upstairs unit with long wide windows and beautiful oak floors, frosted glass panels looking out at 14th avenue. “It’s perfect,” I said, imaging my writing desk in the center of the room, the place where I would finish my next book, a novel set in Denver in the 1930s.

But this was March 12, and the next day a National Emergency was declared, and like so many Americans, I lost much of my income for the remainder of the year in a flash. I told the landlord that I wouldn’t be able to sign the lease, unsure of how I’d make money going forward. I began to search for ways to earn income online — teaching, Zoom talks, book club visits.

During quarantine, I’ve considered my relationship to writing and teaching and a sense of togetherness. During this pandemic, my family and many others have lost loved ones. We cannot mourn our dead together. We cannot gather. We cannot break bread in swampy packed kitchens. Some days have been harder than others, where the collective sadness is so thick that I must search inside myself for shimmering hope, and I have been surprised at my ability to locate that hope. I found it in stories, in teaching, in sharing what I have learned with others. I have found it in books and writing and music.

Throughout quarantine, memories have come to me from childhood. The park where I played house as a little girl, that hollow cement cylinder which I pretended was my mountainside mansion. I’ve called my elders and asked about my Colorado ancestors who came before my lifetime, my people who faced unspeakable challenges and survived it all.

This time has reminded me that I am a writer first and foremost and that my home is in stories, and someday, my future kin will hear of this time just as I have looked to my ancestors for guidance from the past.

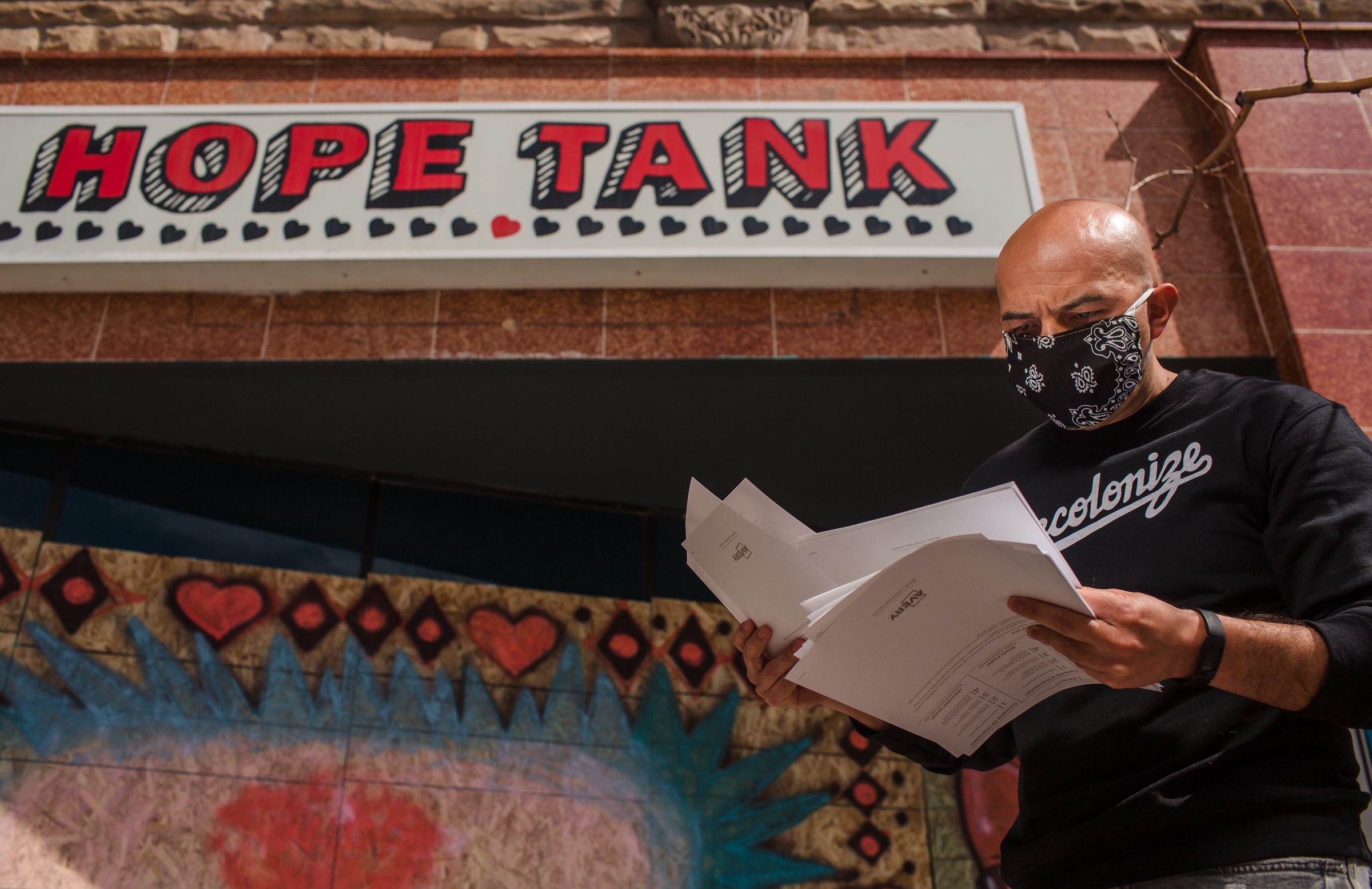

Bobby LeFebre

Colorado Poet Laureate, Playwright

The birds seem to be singing louder in the morning than I can recall in springs past. I cannot tell if their songs are cries of celebration or mourning. Maybe the silence of streets starving for traffic is an amplifier; maybe I am simply listening differently. The collective pause we are living in is a paradox; how can time stand still and fly by so swiftly at the same time? I live alone, so quarantine has graciously allowed me to introduce myself to myself in new ways. This internal archeology, a careful and never-ending excavation. There is something beautiful about wiping the dust away from the bones. Encountering and inventorying relics and artifacts nobody else will see. There is something cathartic about taking the time to archive and categorize thoughts, anxiety, emotions, smiles and tears. I have assembled a time capsule of the times and

buried it deep in my heart. As an empath, the privilege of working from home, thriving artistically and financially, and living without great worry or fear during this trying and unprecedented time is a wandering ghost dressed in survivor’s guilt.

So much of being a poet resides not in what you write, but instead the way you negotiate and reconcile the world around you. We always seem to gravitate to art — and poetry specifically — in times of strife and uncertainty. We do so because poetry has the unique ability to distill collective experiences and create profound connection and meaning. Poetry can be a performer of the collective consciousness and effortlessly hold what the heart and mind cannot. I have been dreaming a lot. Imagining. Resetting. Wondering. Wandering. Asking questions. Creating when something needs to be made, and simply existing when it is time to just be. Through my window, I like you, curiously watched a tsunami approach. There is something riveting about the spectacle. The way your heart seems to cartwheel inside your chest. The way the wave — or the “curve” as we have come to know it — builds as it grows, perplexing the onlooker as to how high it will climb and how much damage it will do. And now, we are all caught in its wake; physically, psychologically, economically, socially. Some are safe in stone towers, others desperately trying to tread water or laying lifeless atop the depths — we know who lives in the towers and who occupies the graves.

I don’t know what tomorrow will look like, but I don’t let that stop me from finger-painting my ideal version upon the sky. I don’t know what tomorrow will look like, but one thing I know for certain is that it will look strikingly different from yesterday. And that, my people, makes me unwaveringly hopeful and grossly worried. Pablo Neruda once asked in his famous Book of Questions, “No te engañó la primavera con besos que no florecieron?” And as those spring birds sing loudly in the morning, I too wonder if spring will deceive us with kisses that never blossom.

Camila Biddulph

Music Desk Editor for 303 Magazine

I saw that the Pentagon released some videos of UFO sightings and I realized that had this been any other year — it would be worth discussing. I’m not all that surprised. If there’s anything I’ve learned about the world as of late, it’s that we don’t really understand anything and that things can change whenever they feel like it. If the world wants an avalanche, it’ll give you one. If we’re due for a pandemic, the box shall be checked on the paperwork, and we’ll witness the grievances regardless. But then we get into the topic of otherworldly, and that’s even harder to define. I’d like to know what the rest of the universe thinks of this development. The humans are all inside, the world seems to be “healing” by their definition via Facebook posts. The otherworldly beings are probably infinitely confused by our rationalizations, by our attachments to money, our worries about imaginary numbers that go up and down dependent on what leaders from different regions announce with fake confidence.

Even more ridiculous, I’m automatically insinuating that they think about us, that when they fly overhead and see our little world, their first thought revolves around the homo sapien condition. How human of me to assume.

If I could tell these otherworldly beings about the world, if they sequestered me among the billions of people mid-pandemic and asked me questions, probed my weirdness and demanded answers — I’d probably turn to music. Whenever I would get tongue-tied or anxious around strangers (when the world had strangers to give), that was my go-to. It’s easy to talk about something you love, and most people love music. It’s the most personal thing you can say without saying anything at all.

So the unidentified would have to get to know the world through its sounds or lack thereof. We’d have to travel to the walls of people’s apartments, townhomes, houses, and press our ears to their noise. I’d give them the Denver tour, starting with Five Points’ history, the stretched out horns walking through the streets. Strut along Colfax, pointing at the venues barred with optimistic “We’ll See You Soons” We’d get hammered by the punk scene on Broadway, drunk off of the guitar riffs, the pitched repression. We’d hover over Red Rocks, the monoliths speaking through their silence, housing memories that are only able to be expressed if you stand on its stage and look out into your fabled crowd.

I’d like to believe the UFOs and their inhabitants, my friends at this point, would get it. Humans are not the most important thing that this world has to offer, and if anything this pandemic has made it clear that the music — which isn’t just a collection of notes we’ve created (have you heard trees when the wind hits just right?) — should be our calling card if the universe chooses to come down and say hello. Even at this moment, this moment where UFOs are secondary news, the world has a thousand songs and melodies pouring out of its lithosphere, creating frequencies that tremble under our collective touch.

THIS is the quality content ive been looking for