Clyfford Still was easily one of America’s most secretive modern artists. Fueled by his distrust of the art world, he was highly meticulous in how and where his work would be displayed. It wasn’t until after his death, when his estate was bequeathed to the City of Denver to create a museum dedicated solely to his work, that the public had access to his influential collection. But even after the debut of the museum, thousands of pieces of art remained unseen — hidden in an archive described as the most intact public collection of an American artist and one of the largest ever maintained by an abstract expressionist.

But as of this September, the majority of Still’s lifework was laid bare in one fell swoop with the debut of an online archive. Despite the seemingly immediate impact of the huge digital drop, the six-year journey to unveiling Still’s work to the world wide web was an arduous one. We spoke with Clyfford Still Museum’s director, Dean Sobel about the process of the digitization of the huge archive, what you’ll find in the massive catalogue and what the secretive artist himself may have thought of the release of his precious pieces.

–

303 Magazine: What was the process like archiving Still’s work? What procedures and precautions did you take?

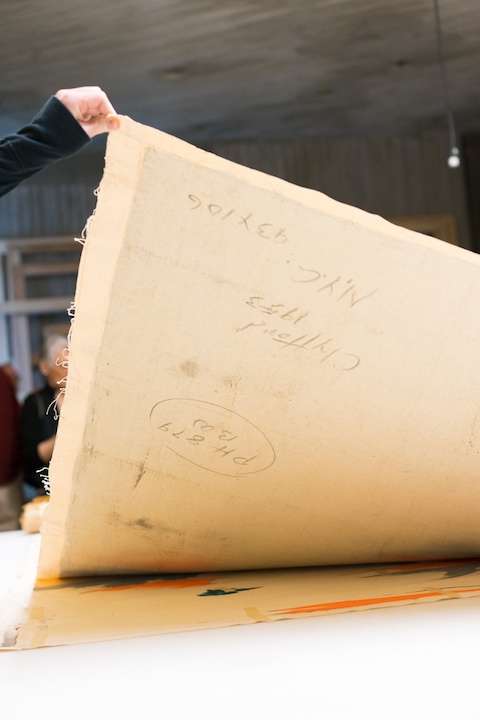

Dean Sobel: For Still’s paintings, every case is unique, and since multiple canvases were routinely rolled onto a single tube by the artist, we had to be prepared for any number of potential situations, including one painting adhering to another. But generally, the cataloguing process consists of unrolling, examining, measuring and taking conservation notes; dealing with any immediate conservation issues; stretching and mounting for storage and eventual display; additional conservation treatment on a case-by-case basis; and photographing each one. To date we’ve inventoried 591 paintings, stretched 469, and exhibited 287 of 829 canvases known to be in Denver’s collection. The process for the collection of works on paper, which is almost three times larger than the painting collection, is quite similar, but the works are matted for presentation and storage.

303: How long did it take and how many people took part?

DS: It has taken six years to get to this point. The Museum’s collections manager, curators, registrar, three conservators and a fine art photographer have all been involved in the process behind publishing each of the 2,223 works of art featured in the Online Collection.

“More than 1,200 of these featured works have never been exhibited publicly.”

303: Not everything is archived, correct? How much remains?

DS: Approximately 70 percent of the City and County of Denver’s collection of Still’s art is included in the Online Collection’s debut. More than 1,200 of these featured works have never been exhibited publicly. The Museum will eventually publish Denver’s entire collection; as of today, 968 works remain to be published online. That figure could change if we discover more works in the process, which has happened several times already.

303. When do you expect to have the full archive up?

DS: Cataloguing the collection is a process of discovery so it is impossible to predict with certainty when we will be finished, but it will certainly be a few more years. As the home of the world’s most intact public collection of an American artist, our work is always ongoing.

303: Why release it now?

DS: We wanted to wait until we were far enough along in the process that there seemed to be a critical mass of material. Another great reason is that 675,000 people just experienced Still’s work in London and Bilbao. It’s fitting that this launch would follow closely on the most widely seen exhibition of his work ever, in his lifetime or since.

303: What are the goals of archiving his work?

DS: One of the key goals in our work is accessibility: making as much as possible accessible to both visitors and those who haven’t — or can’t — get to Denver. So much can be learned with the online collection and its various features and tools.

303: Any tips for browsing the work, i.e. particular decades or areas of the archive that may be enlightening?

DS: Changes in Still’s work seem to be precipitated by changes in his whereabouts, so I do think it is instructive to examine the works according to the locations where they were made, such as San Francisco or New York. It’s also interesting to view them, say, 50 at a time, in chronological order. With this exercise Still’s development from a representational art to near-total abstraction becomes very coherent.

303: Since the files appear to be downloadable is the museum concerned about unauthorized use of the images?

DS: A few years ago museums, almost en masse, came to the conclusion, ‘If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em,’ and starting to make images for research or study purposes much easier to obtain. Again, accessibility is key. Why keep all this material locked down? The rewards far outweigh the risks.

303: Still was considered to be highly controlling over his work. What do you think Still would say if he knew his artwork was online for the world to see, distribute and potentially alter?

DS: The, ‘What would Still say?’ question comes up a lot here and in some cases it’s easier to answer than in others. So much about the world has changed since Still was around. It’s hard to say specifically how he’d feel about the internet, but reproductions were a part of the world he knew, and the online collection presents the work in a compelling and serious way, so I think he’d be pleased with it.

—

Go here to view the online collection. Photos courtesy of Clyfford Still Museum.