After passing a common consumption ordinance in 2019, the City of Denver is planning to begin accepting applications for liquor common consumption areas later this summer.

Denver had originally planned to begin the application process in spring of 2020, but as you can imagine COVID put those plans, and everything for that matter, on hold until social gatherings became safe again.

Now that vaccines are rolling out and COVID cases are stabilizing, the Department of Excise and Licenses is working with City Council to move the process forward. The department requested a change in the ordinance to begin accepting applications 45 days from the adoption of the final rules rather than the current 90 days that’s written, according to Eric Escudero, Director of Communications at the Department of Excise and Licenses.

“We anticipate Council will hold a final vote on our minor ordinance change on May 10. We originally had it at 90 days because we needed that time to get the licenses created and available for people to apply for online. Then the program was delayed because of the pandemic. So, we already have most everything ready to go with just a few other minor things to get ready for people to apply.”

In 2011, Colorado passed a state law allowing local jurisdictions to license common consumption areas. The City of Denver launched a five-year pilot program that was completed in 2017 to study and design the most efficient way that the city could approach common consumption areas before beginning the actual process. If the ordinance to change that application timeline is approved by City Council, the department hopes to start accepting applications for common consumption areas by late July.

“Once the first entertainment district is approved by Denver City Council, we will see a potential flood of applications for common consumption areas in that entertainment district,” anticipates Escudero. “It will be up to the first common consumption applicant to get that entertainment district created, then other common consumption applicants will likely follow in that area. The same thing will likely occur when other entertainment districts are approved by City Council.”

For example if Dairy Block, which is on track to lead the common consumption model as the speculated first applicant, decides to apply for a common consumption license, it will have to create an entertainment district that’s approved by the City Council before obtaining a common consumption license issued by the Department of Excise and Licenses, according to Escudero.

“Common consumption has been legal in Colorado for years and the city has not wanted to get involved too early and learn lessons the hard way. They’ve taken their time to put together a really comprehensive and well-thought-out program,” added Dairy Block general manager Don Cloutier.

To qualify as a common consumption area, applicants must provide the city with a hefty plan that meets various requirements according to the final rules passed by the city on April 15.

The first set of rules ensures that the area will have a concrete health and sanitation plan that describe the retail food licenses within the area, an emergency medical and disaster plan – including response to severe or adverse weather – and list any source of loud noises that might disturb residential areas outside of the common consumption zone.

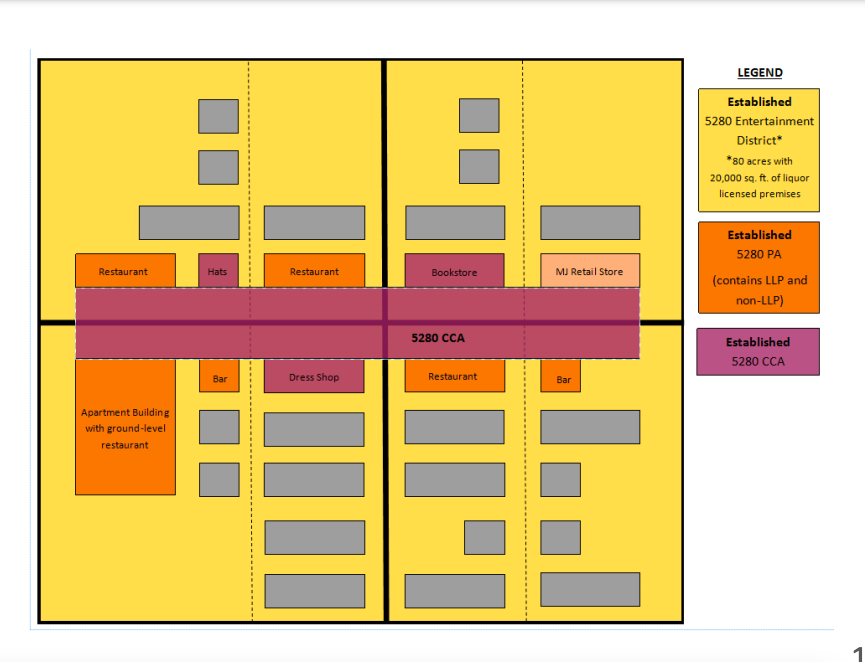

The common liquor consumption area must not be within 500 feet of schools, must be closed off to motor vehicle traffic and alcohol must be consumed out of special cups that denote the original location of the purchased drink. There is also a cap of 100 acres for the entertainment district.

Applicants are additionally required to layout a parking and transportation plan to describe how patrons will enter and exit the area, DUI prevention efforts, public transportation options and a description of the areas physical barriers that provide a buffer between areas outside the approved common consumption zone.

Security and admissions, like the removal of an intoxicated person or prevention of underage drinking, license display requirements and future modifications to approved areas are also outlined in the final rules, along with a community support plan to ensure surrounding residential areas are on board with the new changes.

According to Ashley Kilroy, the executive director at the Department of Excise and Licenses, unlike other jurisdictions in Colorado that have adopted their own common consumption areas, like the Stanley Marketplace in Aurora or Olde Town in Arvada which are designed and chosen by city officials, Denver wants it’s common consumption project to arise organically.

“It’s really going be up to those businesses (to create their own common consumption areas and entertainment district) because there is going to be an effort and intentionality on the businesses part and they’re going to have to work with their neighbors to ensure that their neighbors are excited about it and want to see common consumption.”

In Denver, common consumption areas must be within an enclosed market-type area, according to Kilroy. If in the instance that the area is outdoors, like in a designated alley or street, that area must be closed off to traffic and limit pedestrian access through an entertainment district buffer.

“For example, you could go from one bar on one side of the alley and get a Bloody Mary and then walk over to a Japanese restaurant that’s on the other side to get a glass of sake – and continue walking in the area. But you cannot leave that alley and walk down the street or around downtown,” she explained.

Since the city announced the new laws, neighborhoods and residents around the Denver metro area – particularly those within proximity to places like Dairy Block, RiNo and other potential common consumption area candidates – have been concerned what this could mean in regards to the living conditions in Denver for the future, mainly to the credit of media outlets touting Denver as the next Las Vegas or New Orleans.

However, Kilroy and Escudero want concerned residents and hasty drinkers to understand that this project will not look like Bourbon Street. It will, however, help Denver’s restaurant and bar scene move forward with some clarity and enthusiasm after a year of pandemic hurdles and anxiety.

As liquor laws changed during COVID to accommodate Denver’s struggling food and bar scene, outdoor patio expansions, to-go alcohol and other economic reduce and recovery efforts by the city ended up giving Denver a better idea of some of the challenges that might arise in common consumption areas, making the city even more ready than it was before to handle the new project, according to Kilroy. “We’re ready to get going on this and we’re very excited.”