On October 8, Benchmark Theatre Company kicked off their 2021-2022 season with the premiere of Elephant, an original stage play. Elephant is an intense and visceral interrogation of the legacy left from racism against the Black community in the United States.

Playwrights Neil Truglio, Abner Genece and Candance Joice created the play, which draws inspiration from a series of pseudo-scientific studies conducted in the 1890s titled The Elephant Man. Dr. Frederick Treves of London University Hospital experimented on Joseph Carey Merrick, a Black man with Proteus syndrome, a rare condition causing physical deformities.

Elephant opens with a dramatized version of Dr. Treves (Dan O’Neill) presenting case findings on a man named John Merrick (Nnamdi K. Nwankwo). John doesn’t possess Proteus syndrome in the production but is still treated as a spectacle. John spends the duration of the play living in an empty, worn room of a university hospital wing. Dr. Treves reaches out to Madge Kendall (Courtney Esser), known in the play and real-life as a famous actress. In life and in Elephant, she funds further “research” on John.

The exact purpose of Dr. Treves’s research is ill-defined; audiences watch him use seemingly random tactics to better understand Black people through learning about John. Assuming John represents all Black folks happens numerous times, always met with his push back. John is the only character with a fictionalized backstory. After estrangement from his father, he arrives in a new town and immediately runs into local law enforcement. According to police, he “matches a description” of a suspect-at-large.

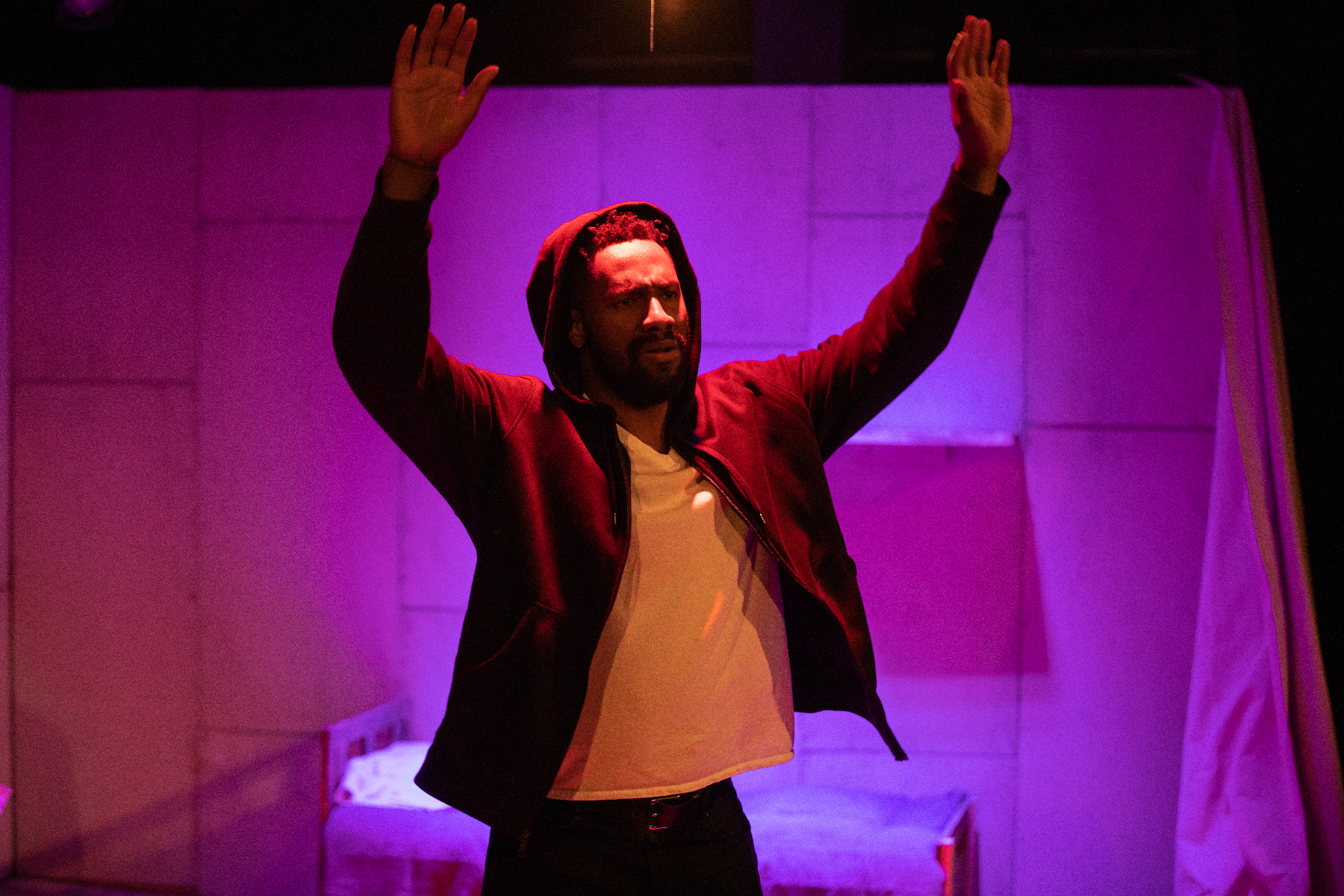

John explains the series of events to Dr. Treves with a physical re-enactment: He holds both hands in the air, falls to the ground as if kicked from behind, wrestles as an imagined police officer places handcuffs on him, shouts that he cannot breathe and writhes in pure agony while asking for his mama. Audience members sat in silence, each holding a different connection to the trauma of police brutality.

How John survives the encounter goes unexplained. He sustained several serious injuries, landing at the university hospital in Dr. Treves’ care. In exchange for recovery and physical safety, John allows Dr. Treves to “study” him.

Madge goes on to take interest in John and visits him on a regular basis. She’s surprised by John’s quiet, sensitive nature, contrary to her perception of Black men as angry and violent. Seeking self-betterment, she relies on John to teach her about racism and the realities of Blackness in America. John refuses to carry this burden, instead handing her a copy of How To Be An Antiracist.

Throughout the study’s progression, Dr. Treves and Madge make constant strides and backslides in their attempts to unlearn biases. They begin to understand the individuality of Black people and differences in privilege but refuse to dive into any conversation they perceive as a direct attack on them. Of course, once they’re comfortable with the idea of Blackness, they begin to appropriate it. Dr. Treves starts wearing a Kente cloth handkerchief; Madge puts on a headscarf culturally belonging to Black women and encourages her Instagram audience to follow suit “in support.”

The playwrights employed sharp storytelling devices, including immersive audiovisual effects and warping the audience’s perception of time. When the play opens, Dr. Treves wears early 20th century clothing, Madge wears a fitted jacket and pleated skirt from the 1890s yet John wears modern clothing. Both Dr. Treves and Madge use antiquated language to describe Black people, including “Negro.” However, Treves uses projected photos from the civil rights era in one of his experiments. For a while, the audience has no idea what year it is.

Roughly an hour in, the audience can confirm it’s present day, yet Dr. Treves and Madge still dress and act like it’s 1895. This blending of time expresses no matter what year, Black people are treated as the other in society. Assumptions made by Treves and Madge that Black people are illiterate and grow up fatherless were popular in 1921 and remain prevalent in 2021.

Elephant connects the past and present treatment of Black people. To the public’s knowledge, studies like the ones conducted on John are no longer in practice. Yet, Black people still find themselves under a microscope. Common tactics include respectability politics and viral broadcasting of acts of violence against them. During the Jim Crow era, public lynchings were commonplace. Today, lynchings live on through hangings and police brutality. Townspeople often photographed Jim Crow lynchings, featuring local white men, women and children gathered around the victim, celebrating. Today, acts of police brutality caught on film instantly become a sensation, allowing anyone to retweet documentation of Black trauma. While documenting police brutality serves as important judicial evidence, it shouldn’t circulate online. This harmful practice reinforces the normalization of Black pain as a spectacle.

Anyone expecting John to have a peaceful resolution is met with a rude awakening, as Elephant makes no concessions. His relationship with Madge comes to a head when she takes advantage of their companionship. Madge, a well-meaning and ignorant white person transcends into a white woman who weaponizes tears and privilege to endanger people of color.

As Madge pulls funding from the study and Dr. Treves moves on to other pursuits, John is last seen readying himself to leave the hospital and reenter the world. His injuries healed during the study, but at what cost?

With strong performances and unapologetic confrontation, Elephant grapples with the dangers and barriers facing the Black community past and present. It highlights the never-ending cycle of attempting to understand Black people without ever truly listening in favor of white comfort. The stage play’s debut is a striking portrayal of generational trauma caused by the exploitation of Black people. Elephant shows the very real consequences of casting a community as “other.”

Elephant will run through the end of October. For tickets and more information about Benchmark Theatre, click here.