When it comes to holding a world view, Denver and Paris-based artist Suchitra Mattai carries a unique and global one. Born in Guyana, South America, Mattai has also lived throughout Nova Scotia, the east coast of the US, Europe and India. Her heritage and constant state of movement seep into her art, saturating her work with symbology that questions colonization, the status quo and the state of the world as we know it.

In her newest solo exhibition at K Contemporary, titled Innocence and Everything After (July 18 to August 15), Mattai showcases nearly 30 pieces that were almost entirely made since the beginning of COVID-19 in March. Recent global events, like the murder of George Floyd, the burning of the Amazon, the global pandemic and more have caused Mattai to focus on the collective “loss of innocence” most people have undergone. She believes that “while some might hope for a speedy return to ‘normalcy,’ these events have unmasked uncomfortable truths about the racial, social and environmental injustices that have been embedded.”

- Installation view

- “Labor and Love”

With the revealing of injustices, society may have lost the innocence it maintained for thousands of years, but Mattai focuses on everything after. “Where innocence has been lost, powerful knowledge has been gained,” she said. According to her, we are collectively coming to terms with past evils and that process involves a lot of questioning of ourselves. “Who does history represent?” “Have I been taught the truth about my own country?” “What is my identity?” Mattai wants to question whether or not we, as a society, could unlearn some of our preconceptions and make space to actually deal with the issues at hand.

To tell this narrative, Mattai chose a quiet storyline. Instead of in-your-face imagery that attacks your preconceptions, she chose to sing lullabies. Beautiful images surround you and whisper you away to a place between reality and dream. The questions are asked in the materials Mattai uses, like women’s hair curlers, rubber cleaning gloves, bindi stickers and various fabrics like saris.

Installation view

“I often focus on women and employ practices and materials associated with the domestic sphere,” Mattai explained.

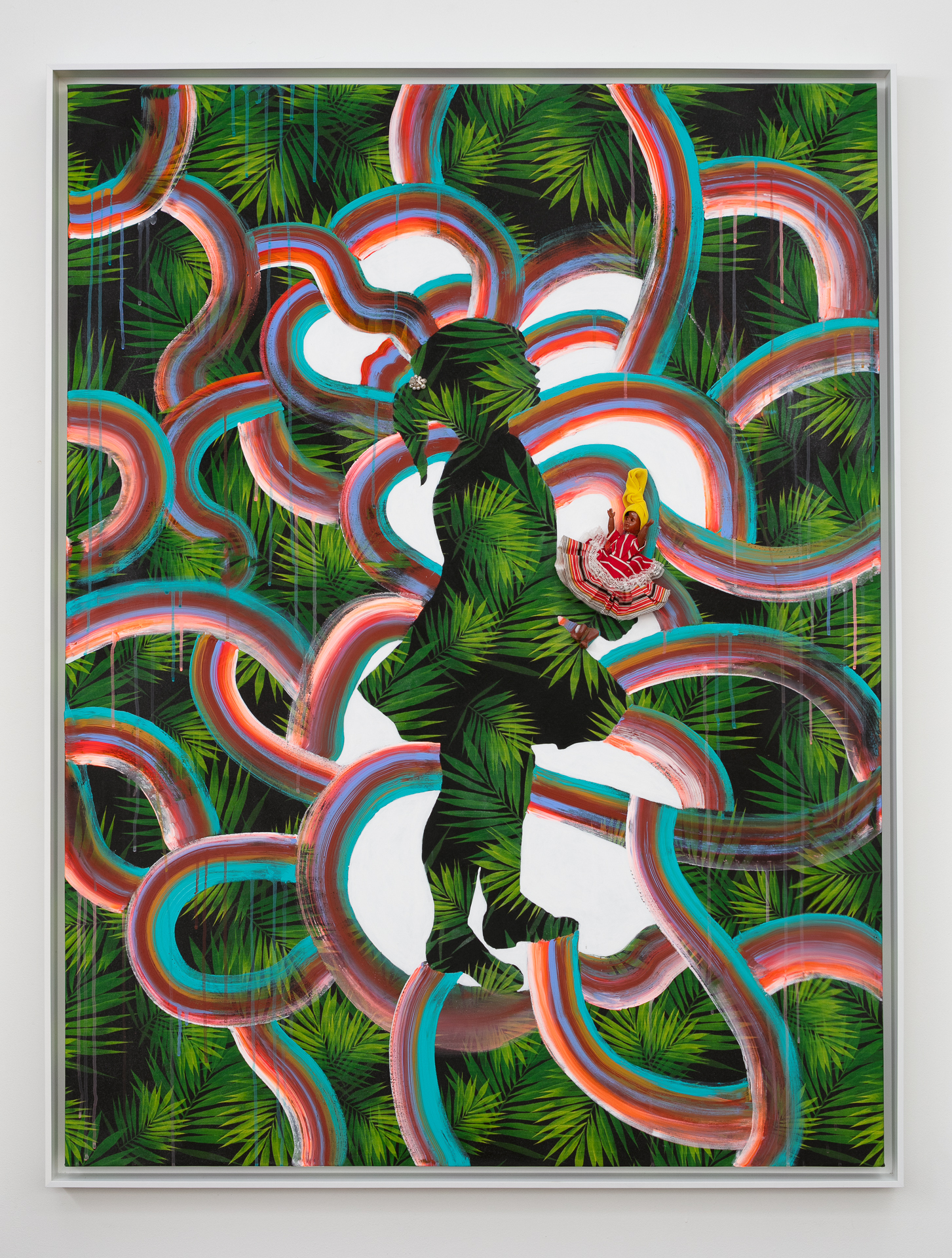

In a few different pieces in this exhibition, Mattai utilizes fabric from the brand Tommy Bahama. In Shelter (Girl with Doll), a black and green leaf design is painted over with multi-colored stripes that drip randomly around the outline of a little girl. In another one, the fabric is mostly obscured by fog-like paint.

“Shelter (Girl with Doll)”

Known for inspiring a certain kind of beachy lifestyle, Tommy Bahama prints reflect a romanticized version of island locations and the cultures that inhabit them. Mattai relishes the reappropriation of prints and patterns like these because she feels like it is an act of reclamation. Reclaiming these prints and reasserting a different historical narrative onto them changes their identity and the identity of those who relate to the patterns. Tommy Bahama through the lens of Mattai’s art represents the marginalized people who have been nearly destroyed by the stiff white men on vacation.

Mattai is adept at fracturing landscapes and narratives and then assembling them within the framework of a marginalized group. She likes to unify vastly different materials to represent her patchwork upbringing and also the necessary assembling of different voices throughout history. Viewers sink their teeth into her installations, sculptures and paintings without feeling like they’re biting into something overtly political. But the bites they take are sweet and sour, filled with the warm touches of femininity while covered in a hardened shell acidified by colonialism, racism and social injustice. There is no piece of Mattai’s that exists without controversy, however small, since she tackles the deepest rooted issues our society faces.

“Invisible Girl”

For instance, in Invisible Girl, first glances provide a cute image of a child surrounded by patterns and color. The dress of the young Black child, however, is made from red-and-white gingham fabric. Gingham is a checkered design fabric that is lightweight and breathable, with the first instance of its name popping up in Dutch-colonized Malaysia in the 1600s. But many cultures have claimed gingham for their own, including the US — even though gingham was imported before ever being manufactured in the country. The story of gingham is littered with appropriation and theft as much as it is decorated with trendsetting celebrities and memories of school uniforms. Mattai serves us the innocent version first, ruins that innocence and then tells us to start over fresh.

This process repeats in piece after piece. Whether she is tackling racial injustice, colonization, inequity or environmental degradation, she lures you in with childlike wonder and then crushes you with honest remarks about the flaws of history.

“Like no Other (tsunami)” (left), “Mirror Image” (center), “Bleeding Heartland (/3)” (right)

In Like no Other (tsunami), Mattai’s iconic interwoven sari design is bisected by a cresting wave made with other fabrics. The tsunami consumes the saris, representative of the disproportionately affected populations of climate change.

In Bleeding Heartland (/3), videos of the Minnesota landscape are juxtaposed by clips from the protests in Minneapolis, as seen through two mirrored silhouettes of young girls. The girls are literally the framework for watching the videos, asking you to see it as they might, asking you to explain it like you’re five. “Why are people protesting?” they might ask. What would your answer be?

Innocence and Everything After offers a hopeful perspective to a world on fire. There’s an oasis that Mattai dreams about — maybe her art will help others see the path to that quenching retreat.

—

“Innocence and Everything After” is on view July 18 through August 15 at K Contemporary located at 1412 Wazee Street. Timed entry registration is required, here.

All photography by Wes Magyar