Accessible art is too often left out of museums. Not only is the cost, and prestige, of visiting a major art museum intimidating, historically the art on display has left out vast swathes of different populations. So for many, a visit to the museum parallels a visit to a world where they are marginalized. Fortunately, exhibits like Returning the Gaze by Jordan Casteel do just the opposite. On view, starting Saturday, February 2 at the Denver Art Museum (DAM), Casteel’s first solo museum show opens the gallery into a gathering place.

Her 29 paintings showcase an intimate perspective of her life through the relationships she crafts with people of all backgrounds, economic status and color. Since Casteel grew up in Denver, her return to the DAM signifies a “homecoming” as director Christoph Heinrich mentioned, but it also seems to be a jumping off point from which the artist will launch her inevitable success. “This is such a surreal moment,” Casteel admitted. “The DAM is a place I grew up [in], doing overnights in the old building, where we’d bring sleeping bags and stay with all of the art.”

Denver is the first stop for this exhibition, though it will travel after August 18, 2019. Some of the 29 portraits were painted just last year, while others were painted in the last five. Casteel, at 30 years old, has a Master in Fine Arts in painting and printmaking from Yale that she received in 2014, so her evolution as a serious artist mainly came as a result of her time at the Ivy League school. However, her passion for painting portraits, and especially painting portraits that revealed that special aura of each subject, started with her family and friends in Denver. Now based in Harlem, Casteel finds no lack of inspiration in the neighborhoods surrounding her apartment.

“A major part of [her work] is seeing people as luminous beings, especially where others fail to notice the light”

Though the exhibition starts at the present, with a painting completed just last year, Returning the Gaze showcases several distinct styles Casteel has moved through in the last half-decade. Some constants throughout are the presence of thick brushstrokes, the mastery of color (take a look at how many different colors she uses in a face, for instance) and the unflinching eye contact from the people in the portraits (also known as sitters).

The sitters are anything but passive models — they are engaged and active in their postures. But they are engaged and active because of Casteel, who spends her time connecting with them despite the bustle of everyday life. Her goal is to elevate each of her sitters to a grand scale. Grand in size, since the paintings are generally larger than the people pictured. And figuratively grand in the sense that she can paint a man who sells furs on a street corner in Harlem with enough compassion, purpose and understanding to transform the average person’s perception of that man. There are three special descriptions in the exhibition next to their corresponding painting — denoted with blue placards — that have a quote from the sitter about their experience with Casteel. These are must-reads, as they contextualize the impact of her work.

“This entire show is deeply connected to me. These are real living people. They’re alive and well and friends of mine. It represents my life, and looking at all of them now feels like pulling a scrapbook out of the closet, where I genuinely remember how I felt when I made a brushstroke,” Casteel commented.

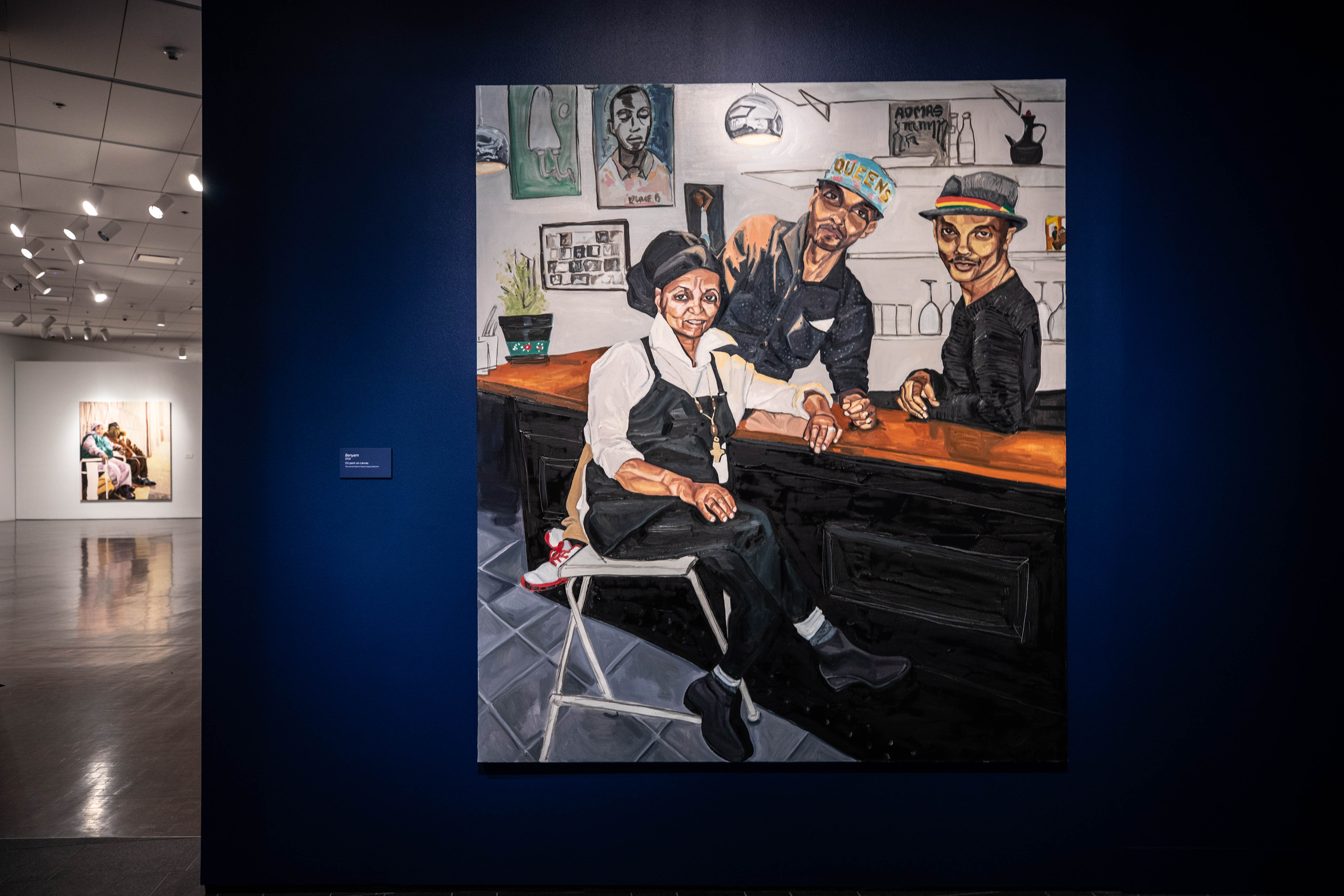

Returning the Gaze begins with Benyam — a painting featuring two younger men with a woman (their mother) in front. The subjects are the owners of an Ethiopian restaurant that opened near Casteel’s home in Harlem not too long ago, and within the painting, there are hints of the relationship that Casteel has already fostered with the business owners. A “little shrine” the artist lovingly called one peaking corner of a postcard in the background of the painting, where the sitters had set aside an announcement of an art gallery show of Casteel’s.

The next section is more closely related to Casteel because each painting features close friends and family members, beginning with her mother. Together with the first painting, the familial section provides an interesting segue into the rest of the exhibition. Because the other sitters are strangers that have become friends and family, rather than friends and family that posed as sitters, the intensely intimate initiation into her work serves as a kind of artistic lubricant. It’s easy to feel how Casteel feels about her family, as many of us come from a place of understanding on those matters. But the true exhilaration of her work is found in seeing the soul of a total stranger — the meaty definition of empathy.

Which is why the next section is the heart of the exhibition, where portraits of a variety of people on the streets populate the walls. Some of the subjects, though they were relative strangers to Casteel at the time she photographed them, have now become close friends and confidantes. The best example of this is the portrait of Yvonne and James, who are pictured together on a bench outside of a well-known Harlem restaurant, holding hands. Casteel first painted James by himself and when Yvonne (his wife) saw the painting hanging in an art gallery, she told Casteel “thank you for seeing him how I’ve always seen him.” It is in this section that viewers start to grasp the emotion entrenched in Casteel’s work, and the consideration she bestows upon her subjects. Painting, for her, is a tool to relate her experiences to others. And a major part of that experience is seeing people as luminous beings, especially where others fail to notice the light.

Following the series showing people in Harlem, Returning the Gaze moves further back in Casteel’s career to 2014, at the end of her time at Yale, with the body of work called Visible Man. These paintings all depict nude black men — all of whom Casteel found in the Yale drama school — and yet almost none of them are painted with actual skin tones. “Elijah” was the first, and his skin ranges from pale green to rust to light yellow to gray. Posed in the comfort of their own homes — in ways reserved for the most intimate situations — these sitters expose the delicacy and fragility of black men as seen through the artist’s eyes. Her experience as a woman of color who interacts with men of color informed this series deeply, where her desire to reveal them as partners and lovers exudes from each and every brushstroke. But, perhaps even more remarkably, each of the men in this series came to her as a stranger via an email request she sent blindly. Her ability to dissect a subject without cutting apart their essence is unmatched in any contemporary portraiture I’ve seen yet.

The final room of the exhibition is founded on Casteel’s new source of inspiration — the subway. Although she has spent years connecting with people, neighbors and strangers on the streets around her apartment, the subway series comes as a result of observing from afar. Casteel sneaks photos of people’s hands and then returns to her studio to paint them without the subject ever knowing. These smaller paintings lack the eye contact of the rest of her work, but the connection to the (unknowing) sitter still feels visceral, through the inclusion of their hands. Hands, after all, are indicative of a person in many ways — through their jewelry or watches, the care taken with their nails, the wrinkles or sun damage. The two largest pieces in the final room on the back wall keep true to Casteel’s known style, with a family pictured in one and a woman in front of her bakery cart in the other, and have been acquired by the DAM.

Although it’s easy to stop and stare at these larger-than-life paintings (and some amount of ogling is encouraged), Casteel wants her work to engage the viewers as much as her work engages her. In order to help facilitate that, there are cards at the beginning of the exhibition which includes prompts like “slow down and observe what is around you.” Don’t be afraid to talk about the work with others, enjoy the video featuring the animated and well-spoken artist answering questions and use the compelling images as motivation to return your gaze to someone new — someone you may usually just pass by — once you leave the museum.

—

Returning the Gaze will be on view at the Denver Art Museum from February 2 through August 18, 2019. The first day falls on a Free Saturday, and this exhibition is included in the price of general admission.