Exposed. It’s an evocative word. It reminds us of uncovering secrets or revealing something private. Denver’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) embraces the act exposure this summer with the exhibitions of Jenny Morgan and Derrick Velasquez, which opened Friday, May 26. Both of these artists explore the boundaries of hidden spaces and ideas, which opens the viewer up to the possibilities of confronting our own boundaries.

Morgan exposes the human figure and uses special techniques to blur the traditional concept of portraiture. Velasquez, the Denver-based artist who is most notably known for his vinyl pieces, has installed two site-specific installations and a photographic series which question the functionality of design, art and architecture. Ryan McGinley‘s The Kids Were Alright (see our article about his exhibition here) remains on the second level until August — a nice complement to the exploration of boundaries theme that Morgan and Velasquez embrace.

Jenny Morgan

Morgan was born and raised in Salt Lake City, Utah but is currently living and working in Brooklyn. She is sometimes noted as a Denver artist because of her time as a student at the Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design (RMCAD.) Her exhibition, SKINDEEP, is a look back on her career in the last 10 years, following the evolution of her painting technique as well as her subject matter. It is an intimate collection of larger-than-life paintings in the main level galleries that expose delicate emotional states through body language and facial expression — both literally and figuratively.

As a young artist, Morgan mastered portraitures in classical ways, providing a likeness of a person with striking accuracy. As her artistic career progressed, she experimented with her paintings while keeping the subject matter the same. Using sandpaper, she strikes away layers of oil paint after completing the basic portrait, unveiling different gradients that would normally be covered and also highlighting the natural texture of the canvas. In her earliest work (seen in the first gallery) red plays the starring role, often taking over the portrait in a way that resembles burned skin. This technique, mixed with the facial expressions of her subjects, make the paintings raw and primal.

With more exploration of this novel technique, Morgan’s paintings transitioned from haunting to spiritual. Her interest in the occult, the Tarot and shamanic ceremonies influenced how she wanted to use the sandpaper process and how she wanted to portray the people she painted. Instead of the ultra realistic portraiture of her early career, she wanted to present a state of being through her paintings — an emotional aura. The sandpaper became a way to strip away the facade of her subject and fixate on their inner expressions.

There is an entire room dedicated to Morgan’s self-portraits because she paints a lot of them. Usually, every third painting she completes is one in her own image. “It’s about confronting yourself continually, for any artist and maybe for every person. But also, I know that painting myself comes with no consequences,” Morgan explained, while standing in front of one of her 70-inch tall self-portraits. That portrait is actually part of a diptych, the other part of which depicts her doppelgänger — a woman who grew up in Salt Lake City, too.

“Self” and “Doppelgänger” by Jenny Morgan

The counterpoint to the majority of Morgan’s work is her commissioned portraits of celebrities for New York Times and New York Magazine. Because of her background in illustration, Morgan was able to produce each one of these in just five days — her other paintings typically take two months. But the main point of departure of these works from her personal portraits is that she had to include all of the accouterments — jewelry, clothing, make-up — that she prefers to avoid, and in doing so, included the facade of the subjects that she would normally peel away.

Celebrity portraits by Jenny Morgan

Derrick Velasquez

Velasquez stands in front of his photographic series, “Property Lines”

Velasquez is a Denver artist represented by Robischon Gallery, who has been teaching at University of Colorado Boulder, University of Denver and Metropolitan State University since 2010. He is the founder of Yes Ma’am Projects — an organization that “supports contemporary, individual artists, at any stage of their career, through unrestricted cash grants and potential exhibitions in alternative art spaces.” The Denver art community has been receptive to Velasquez’s efforts to support Colorado creatives through the appropriation of those grants.

His exhibition at MCA Denver, Obstructed Views, scrutinizes the “figurative borders between art, design and architecture,” using the actual MCA building as part of his artistic process for one of his site-specific installations by decorating the opening between the main level and basement. Velasquez likes to work in layers, thinking of his art as a process of learning and discovering in intertwined loops, which leads to many of his pieces having multiple interpretations.

The photo series in the Whole Room gallery, downstairs, depict property lines in Denver that separate old and new developments. By focusing on these barriers, Velasquez highlights the metaphorical nature of a boundary, or as he explains, “My work teases out our psychological relation to the dimensions and conditions given by such materials.” Although the immediate association with these photographs is the gentrification process, Velasquez focuses on the building materials of that gentrification rather than the consequences of it.

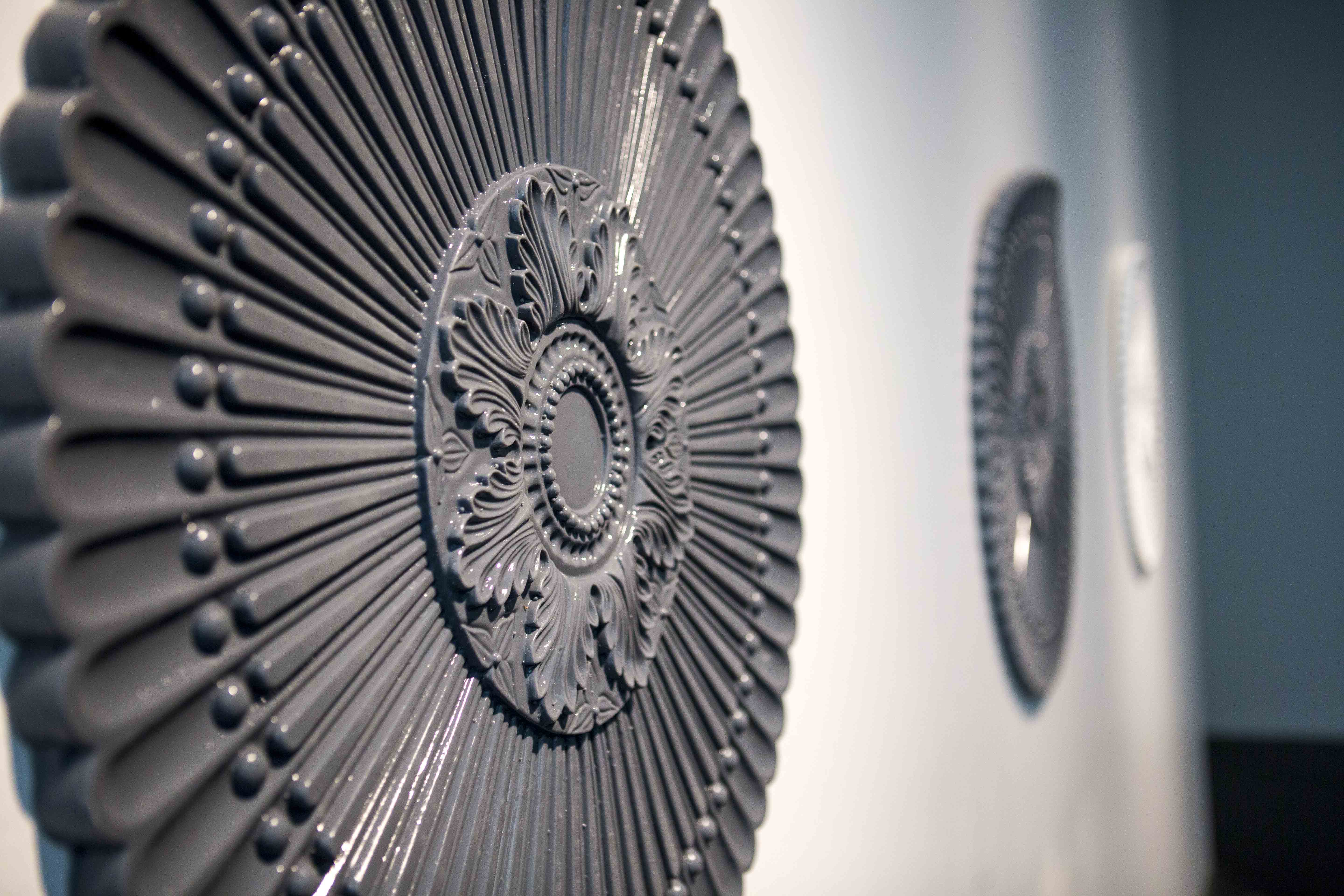

Decorative molds, filled with silicon.

The other pieces in Obstructed Views showcase Velasquez’s attempt to reconfigure the functionality of design. Instead of critiquing the desire to design our surroundings with frivolous items, he meditates on it. With materials traditionally used for building and construction, like steel pipes, concrete and the decorative molds (pictured above), he takes away their functionality by separating them and emphasizing their individual aesthetics.

The jewel of Velasquez’s exhibition is his site-specific piece in the atrium opening between the main floor and the Whole Room gallery — an enormous gaudy and gold frame. Created with cheap foam molds (used in McMansions, for instance) spray-painted gold, each layer of the frame represents a different style but when seen all together, there is a distinctly rococo feel that harkens to the desire to look fancy rather than actually be fancy. Is everything about appearances, or does it need to have purpose? Velasquez noted that he has always wanted to install something in this space at MCA. By looking down from the main or second floor into the frame, the black floor creates a blank space for the viewer to fill in with their own imagination.

Derrick Velasquez stands below his frame.

The act of exposing carries with it a heaviness because in order to be able to expose something, it must be hidden to begin with. One must dig deep, peeling away layers and perceptions until something raw, bare and vulnerable remains. Art like Morgan’s and Velasquez’s, which expose tangible and intangible secrets, is a remarkable way to acquaint a viewer with his or her own secret to uncover.

Morgan’s SKINDEEP and Velasquez’s Obstructed Views are on view at MCA Denver, 1485 Delgany St., until August 27 and were both curated by Zoe Larkins.

All photos by Amanda Piela