Some 15 years ago, Ryan White was hiking Devil’s Head Lookout Trail, the classic out-and-back trek near Sedalia, when he noticed a swath of juniper berries. Knowing that gin derives its predominant flavor from juniper berries, White—perhaps in a way not dissimilar to countless amateur explorers and foragers before him—had an idea: to impart the piney flavors from said berries into spirits. After briefly looking into the permits and legal hoopla associated with establishing a distillery, White shelved the thought because of the extensive barriers. That is until 2012, when he decided to embark on a journey that would ultimately alter the future of distilling in South Metro Denver.

After working 20 years in sales, most recently as a manager for a California-based flooring company, White admits he felt completely burnt out by the corporate world. Plus, he considered the foreseeable challenges of opening a distillery a personal mission of sorts. So with no prior distilling experience, and a completely unrelated sales background, White decided to quit his day job.

While he was aware of the numerous logistical roadblocks in opening what would eventually become Devil’s Head Distillery, what he didn’t know is that he’d eventually spearhead a nearly two-year, one-man movement to modify Prohibition-era laws in Englewood and Littleton.

Although the state of Colorado boasts lax distilling laws, municipal and city ordinances still dictate specifics such as distribution and production. Because of stringent laws, before distillers even open their doors, the federal government must approve all recipes. In other words, distillers are required to establish a legitimate operation before they begin production.

“You can’t really open without being ready to go,” explained White.

Logically, the first step in any distiller’s journey is securing a location. Born and raised in Littleton, White knew he wanted to set up shop in either his hometown or in bordering Englewood. Not only was White familiar with South Metro Denver, he claims that he wanted to stay away from the saturation, and expensive leases, of downtown. But before he could get too far, White realized that Prohibition-era laws prohibited commercial distilleries in both municipalities.

“In Englewood, they had a strict prohibition against [all] distilleries—it was directly stated that distilleries were prohibited,” said White. “Littleton was a little different. They allowed them in industrial zoning areas, even though they’ve never had one, but they didn’t allow anything in retail and commercial [zones].”

Due to the benefits of public exposure and visibility, opening in both a retail and commercial capacity was important, even critical, for White. For Devil’s Head, White intended to place an emphasis on the public-facing tasting room and retail side of operations. Rather than concede, and open shop in Denver, White decided to fight the law.

White assumed that changing the laws would simply be a matter of gaining the interest of necessary city officials. He thought that both municipalities would naturally want to modify the laws, and that the only reason they hadn’t been updated is because they’d never been challenged. Because of these assumptions, White decided to go it alone—despite the fact that he was told he wouldn’t be able to change the law without an attorney.

“I just thought that it was something that would flow naturally and easily,” he said. “That wasn’t the case necessarily, at least to the degree that I had anticipated.”

As it turns out, changing the law was a far more involved process. White’s first step was to draft letters to city officials that he could find contact information for: city managers, city council members, and each municipality’s mayor. After receiving unsatisfactory replies, he began to attend city council meetings, where he vocalized his mission during public comment portions. White’s concerns were received, although he was told to bring them elsewhere. More specifically, officials in Englewood required that bring his case to the Planning and Zoning Commission.

White heeded this advice and again, attended numerous meetings. Due to bureaucratic delays and bigger, immediate projects—including the rapid development of both municipalities—it still took time for his concern to be fully addressed. White eventually met with economic development chairmen and city planners to discuss his vision for Devil’s Head Distillery. They discussed the benefits and contributions that a distillery could bring to a municipality, including tax revenue, job creation, and tourism opportunities. Despite the delays, White says that once he got started, he was generally able to gain the interest of those involved.

After countless meetings, and nearly two years of waiting, White’s efforts paid off. Englewood and Littleton revised their zoning ordinances on October 6, 2013 and November 19, 2013, respectively, to allow breweries, distilleries, and wineries in industrial and commercial zone districts. And about a year later, on September 4, 2014, White opened Devil’s Head Distillery a block from the Gothic Theatre—thus fulfilling his initial vision from the day he encountered those juniper berries.

White says the number of planning and zoning meetings that he had to attend, in addition to keeping things moving forward, were his primary challenges. Although the process was time-consuming, and downright difficult at times, he admits that opening a distillery in Denver would have been a shorter process—although it wouldn’t have yielded a remarkable story.

“It [was] brutal at the time,” he said. “But in retrospect, there’s a sense of fulfillment for participating in the community.”

While the distance between I-25 and 285 on South Broadway is less than 4 miles, since September 2014, three distilleries have opened on this stretch: Laws Whiskey House, Bear Creek Distillery, and most recently, Devil’s Head. It may be too premature to call this area “Distillery Row,” but like the River North Arts District did with craft beer, this South Broadway strip could evolve into something of a destination for craft spirits connoisseurs.

No matter what the future holds for distilling in Englewood, Littleton, or even the city of Denver, it’s safe to assume that White’s efforts are far-reaching.

“It is interesting to look back at [pre-Prohibition] and that part of history, and say that I’m the first one to bring it back to Englewood,” he said.

All photos by Matt Pangman.

—

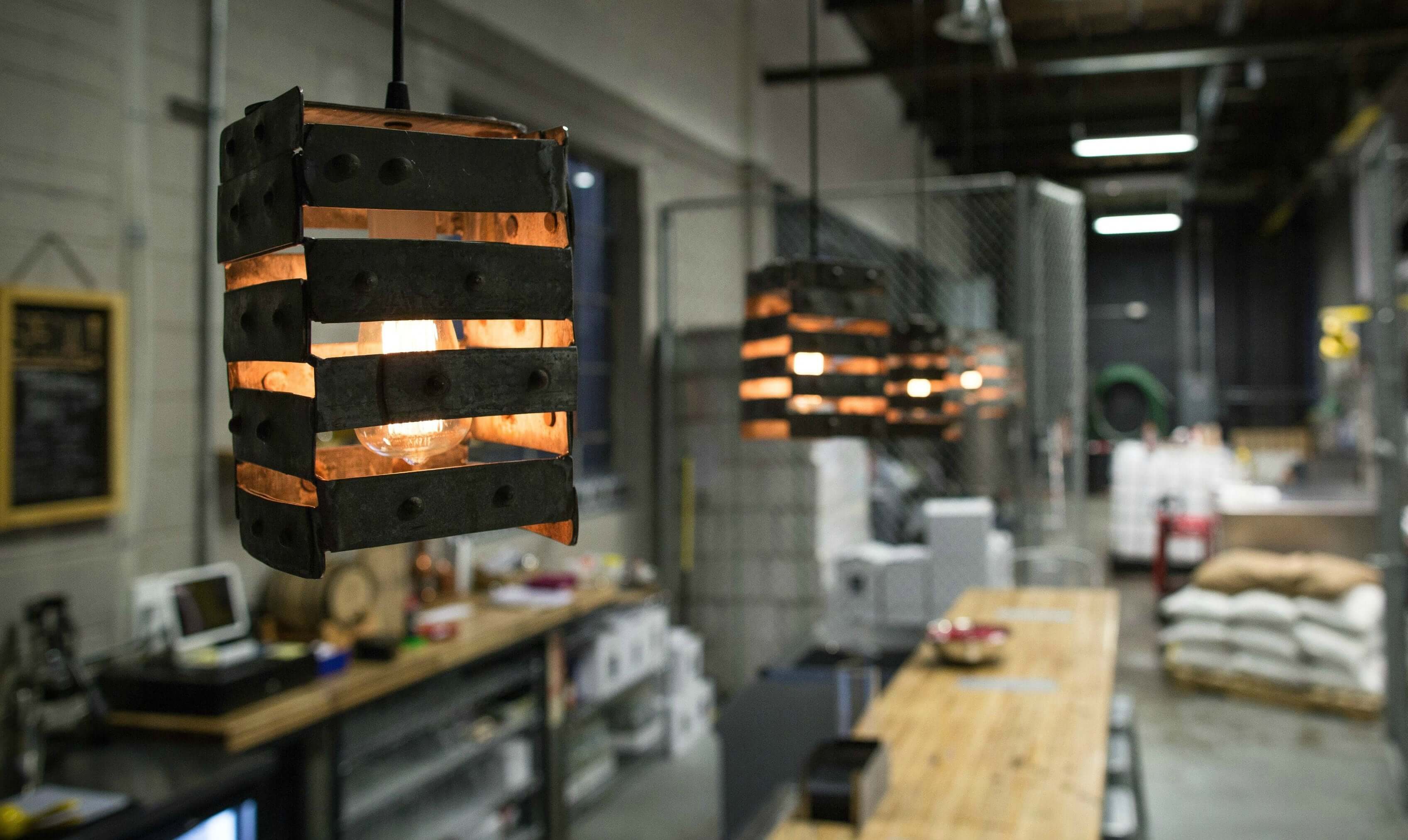

Devil’s Head Distillery is located at 3296 South Acoma Street, in Englewood, Colorado and is currently opened on Fridays and Saturdays, from 4 – 11 p.m. White is currently distilling and bottling gin, vodka, and aquavit, a Scandinavian spirit that derives its flavor from caraway and dill. In addition to its bottles for purchase, Devil’s Head features seasonal, rotating craft cocktails in their taproom.